Back to the American Revolution! In the last post of this series, we’ve seen the American Patriots successfully establish a military footing, taking Boston, and even invading Quebec. This time, we’ll look at the fight for New York, the retreat of Washington’s Continental Army, and finally the American counter-attack in the winter – as always, with board games!

You can read all articles of this series here:

“Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death!”

The War of Independence: 1775-1776

The War of Independence: 1776-1777

Up Against the Wall: New York

After the British defeat in New England, they looked for colonies more sympathetic to them. The south, the British commanders were informed, was full of Tory loyalists. However, British tentative approaches to land forces in North and South Carolina met with fiercer Patriot resistance than expected, while the promised Tories never turned out in great numbers. Thus, these plans were abandoned.

Instead, the British turned to New York, the largest city in the colonies, its commercial hub, and the seat of George Washington’s headquarters. The British strike at New York, run by the brothers William Howe (commanding the army) and George Howe (commanding the navy) would be the single largest operation of the entire war, containing tens of thousands of new recruits, many of them mercenaries from the German states, especially Hessians.

Initially, the British offensive went well: Washington had split his forces between Manhattan and Long Island. The British landed on the latter and engaged Washington there in a major battle (August 27, 1776). The Americans were soundly defeated by the quantitatively and qualitatively superior British forces.

Backwards: Washington’s Retreat

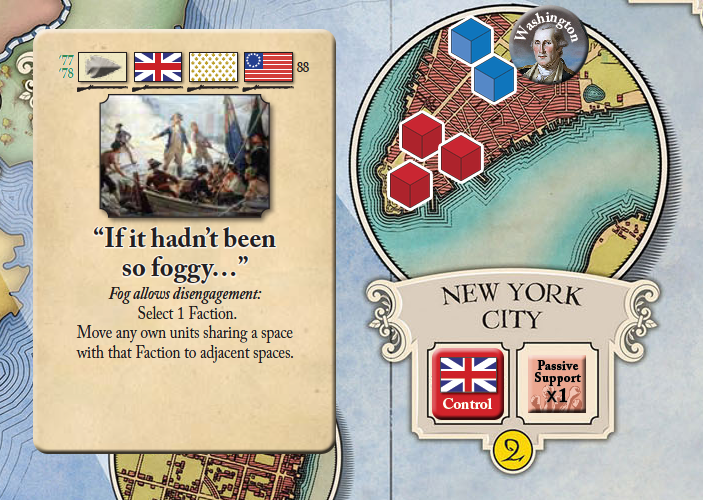

As the Howes had hoped for a quick negotiated settlement after showing their superior military might, they had neglected to cut off the retreat routes. This lack of determination cost them dearly – the Patriots had no intention of coming back into King George’s fold. Instead, Washington and his army retreated to Brooklyn, crossed over to Manhattan and later slipped away in an unseasonable fog (one of several instances of fog referenced in Liberty or Death (Harold Buchanan, GMT Games)) north of the Harlem River, leaving a force behind in Manhattan to defend the fort there.

Howe followed Washington slowly. He beat him once more at White Plains (October 28, 1776), but squandered the opportunity to force a major engagement. Instead of pursuing the Continental Army further, Howe turned back to New York and took Fort Washington.

Washington crossed the Hudson and moved across New Jersey into Pennsylvania. Here, his trail was taken up again by British general Charles Cornwallis, a more energetic commander than Howe, but by no means more competent. While that assessment may sound damning, the fact remains that the British leadership in the war lacked energy much more than competence – and thus Cornwallis’s more aggressive style might have been just what Britain needed to come to grips with the Patriots. Players of Washington’s War (Mark Herman, GMT Games) might certainly think so, given that Cornwallis is one of only two British generals (out of five) that can be activated with a card of less than the maximum value of three (and thus will often be the workhorse employed to snuff out Patriot resistance in active campaigns, while the more stolid generals with higher battle die roll modifiers statically defend important ports).

With Cornwallis approaching, the Continental Congress – which had boldly declared independence just a few months before – abandoned Philadelphia. Washington’s army was down to 5,000 men.

Crossing the Delaware: The Counter-Attack

George Washington was no Julius Caesar, no Gustavus Adolphus, and no Frederick the Great. His style of generalship was solid, workmanlike, and usually risk-averse. Yet in the desperate situation of December 1776, more than that was required. And Washington rose to the occasion with his one stroke of brilliance.

In the night of December 25, his little army crossed the Delaware River and attacked the Hessians at Trenton, New Jersey. The Hessians were taken entirely by surprise and routed. American morale soared. Cornwallis pursued Washington with his aforementioned mixture of energy and incompetence. Washington evaded, launched another surprise attack in Princeton, New Jersey, and beat the British once more (January 3, 1777). After the demoralizing defeats which had marked all of 1776 for the Patriot cause (besides Washington’s defeats and retreats, there had also been the abandoned invasion of Quebec), the winter campaign had been stunningly successful. In a nod to this brilliant stroke, Washington’s War gives the Americans a +2 die roll modifier when attacking with Washington on the last card play of a year – which means the British generals always sit a bit uneasily in their winter quarters, bracing for a last blow.

Washington’s successes had revived the Patriot cause in the eyes of its supporters. Recruits flocked to the Continental Army. The Patriots were ready for the campaign of 1777.

…but that’s a story for next time!

Games Referenced

Hold the Line (Matt Burchfield/Grant Wylie/Mike Wylie, Worthington Games)

Liberty or Death (Harold Buchanan, GMT Games)

Washington’s War (Mark Herman, GMT Games)

Further Reading

Allison, Robert J.: The American Revolution. A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, New York City, NY 2015 is exactly what it says on the tin.

Higginbotham, Don: The War of American Independence. Military Policies, Attitudes, and Practice, 1763-1789, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN 1977 covers not only the campaigns, but also the political, social, and economic dimensions behind them.