In addition to all the articles we’ve published, and before properly moving onto Spring titles, enjoy this lengthy compilation of comments and short essays about other works that have impressed us early in 2025. There are some notes about big hits of course, but also a look at specific moments that elevated shows, smaller works that nonetheless deserve attention, and a space for the indie and avant-garde as well.

You may have noticed that we shared quite a few articles today. If the reason wasn’t clear enough, it’s because we initially intended to publish a single roundup about works of animation that had impressed us across the first months of 2025; mostly ones released this very year, though as you’ll see later, also independent ones that are less bound by temporality. After splitting a few write-ups into self-contained posts, we’re left with a collection of last yet definitely not least notes. Don’t expect these works to be lesser, nor the write-ups necessarily less in-depth. These are simply smaller-scale highlights, be it because they’re shorter works or because specific episode directors raised the bar far above their show’s norms.

Cocoon is a stunning, Miyazaki-flavored training effort… with a darker side to it

Cocoon is a harrowing short manga by Machiko Kyou, centered around a group of young girls that parallel the situation of the Himeyuri students during World War II. Its dream-like quality, according to the author’s afterword, has much to do with the way she personally envisioned it: as the type of hazy nightmare that a child might have when reading history books about wars of the past. Perhaps even more importantly, it’s also tied to the central motif of this work and the worldview behind it. Submerged in tragedies of a caliber that no child should witness, the girls—especially its imaginative protagonist named after the Sun—shield themselves from reality with their companionship and fantasies, which spin a sweet cocoon to protect them. But is that going to be enough to keep any of them safe in such an unforgiving situation? Or, as Kyou succinctly phrases it: can sugar rust steel?

For as interesting as it is, Cocoon isn’t a manga I would lightly recommend. Its graphical depictions of death, dismemberment, starvation, near sexual assault, and rotting alive of children aren’t gratuitous in the sense that contrasting them with the sweet fantasies is what the series is all about, but it’s still haunting imagery. Given that animation undergoes stricter standards when it comes to extreme portrayals, one of the biggest questions I had when it was originally announced was how such a story could be conveyed. The fact that the project would be geared toward mentoring young animators seemed fitting (almost too fitting for an animator training project to be about children dropped into a warzone), but otherwise, how could Cocoon be animated? The answer that its team arrived at is, in a way, to film it from within the proverbial cocoon.

Instead of attempting a straightforward adaptation, the Cocoon anime transports the characters into a slightly more traditional, lengthier character growth story to fit its one-hour runtime. Similar situations are reimagined whenever they’re considered particularly important, like the introduction of the idea of the cocoon at the very beginning. Hearing the comparison between the atmosphere of a snowy day and being enveloped by a cocoon, the storyboards make the characters overlap with a cloud that mirrors that idea; the opposite type of weather to the one they’re describing, and yet a striking appearance of the central motif in this story.

Instead of attempting a straightforward adaptation, the Cocoon anime transports the characters into a slightly more traditional, lengthier character growth story to fit its one-hour runtime. Similar situations are reimagined whenever they’re considered particularly important, like the introduction of the idea of the cocoon at the very beginning. Hearing the comparison between the atmosphere of a snowy day and being enveloped by a cocoon, the storyboards make the characters overlap with a cloud that mirrors that idea; the opposite type of weather to the one they’re describing, and yet a striking appearance of the central motif in this story.

One aspect that stands out just as fast is the uncanny ability to channel the energy of Hayao Miyazaki’s works. We live in a world obsessed with finding his successor, where artists with Ghibli experience contribute to all sorts of projects—including those made at direct offshoots from the studio, like Ponoc. Cocoon can boast of a similar pedigree; art director and color designer (Yoichi Watanabe and Nobuko Mizuta, respectively) with Ghibli films in their resume, ace animators like Shinji Otsuka and Akihiko Yamashita that are inseparable from their works, and most importantly, the fact that it was produced at Sasayuri.

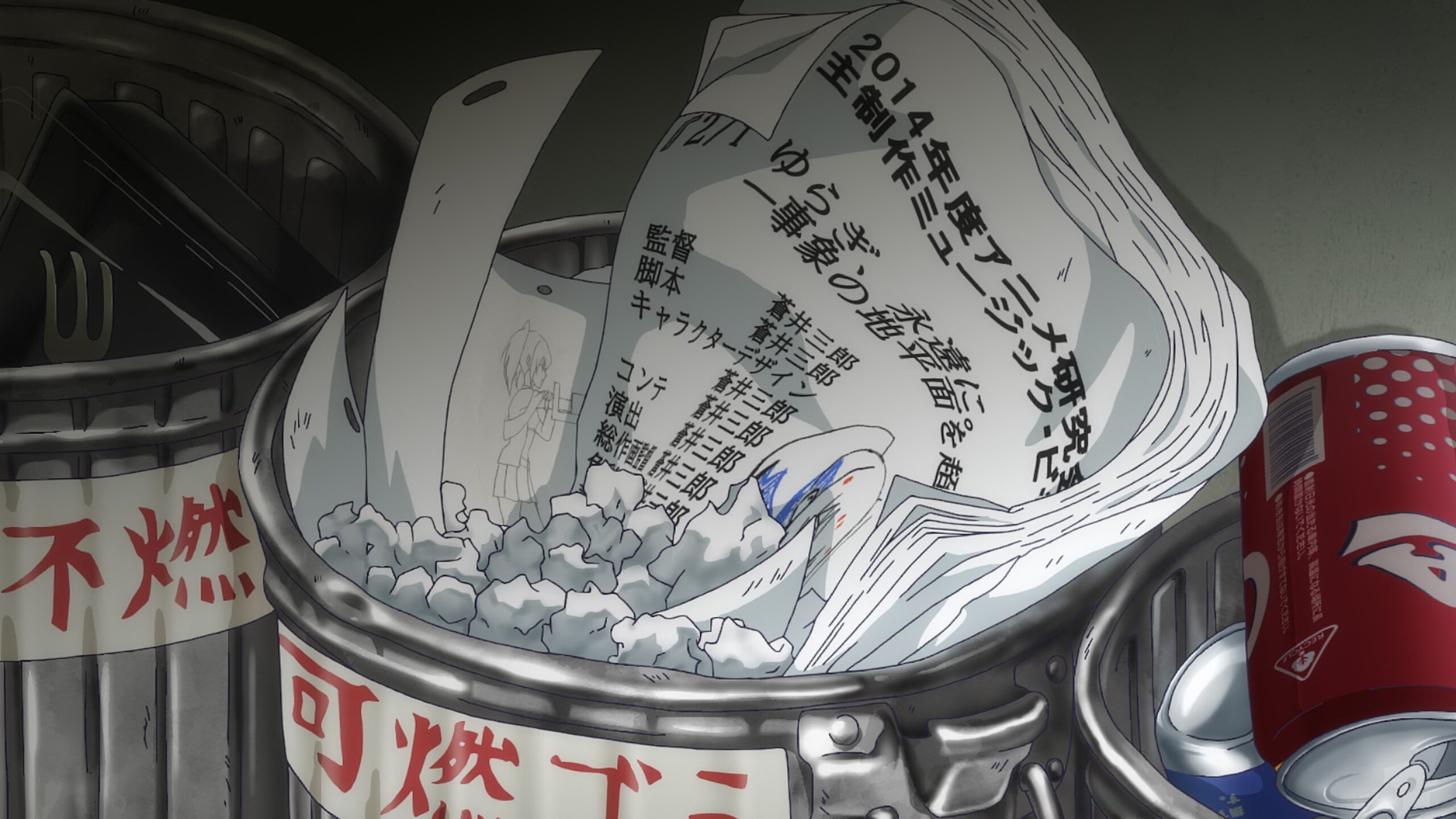

For those unaware, the company was founded by renowned Ghibli douga veteran Hitomi Tateno. After a long tenure at the studio, she left behind the stress of production in favor of something she loved just as much as creating animation: mentoring other artists. She first did it in the inherently laid-back environment of a café, and while that sadly closed down when the pandemic struck, she’s been able to follow it up with the establishment of an animation production department. With it, she can grant real-world experience to the students who undergo the Sasayuri training course, which has gained a fair amount of notoriety because of her credentials. Promising youngsters have been joining them and immediately standing out in demanding environments, and the scope of their own projects has been steadily growing. In 2019, they were aptly appointed to handle the animation for Natsuzora—a story inspired by another historically important woman in animation, Reiko Okuyama. Over the last few years, they’ve taken things up a notch and decided to produce their first film: Cocoon.

Even with that relationship with Ghibli and the access to extraordinary talent, both veteran and fresh, it’s remarkable how well they captured the body language and cadence of a Miyazaki work. None of the aforementioned heir candidates have ever (not that they were under any obligation to, though they’ve certainly tried) managed to mimic the emphatic acting and modulations of the animation that everyone associates with Miyazaki. There’s a sense of posing you could find in his pre-Ghibli work as well, featuring a thick Yasuo Otsuka flavor. It fixates on the undulations of emotions as the camera gets closer to people’s faces; with that stubbornness against partial holds it shares with the movies that inspired it, which makes the lines feel constantly alive. The timing of the sequences is as recognizable as the individual cuts themselves, with a tendency to make you hold your breath before it unleashes crowds like a dam just exploded. Scenes like the preparation for the first air raid and this later moment of chaos embody those tendencies perfectly.

Above all else, this is a mind-blowing achievement from director, storyboarder, animation supervisor, and co-scriptwriter Yukimitsu Ina. He’s still a young artist himself, barely a few years removed from being mentored in Yukiyo Teramoto’s The Chronicles of Rebecca (2020). And yet, despite having no real experience with this stylistic register other than his participation in the aforementioned Natsuzora, he showed a deep understanding of Miyazaki’s animation tendencies and how to use them to evoke powerful feelings. In the end, the result isn’t as polished as a Ghibli work; it would be unreasonable to expect it to be, given its focus on the mentorship of youngsters. It does, however, feel like a very fitting angle for Cocoon to take due to the already existing link between Miyazaki’s work and the War. It’s borrowing not just a language but a context, and deploying it in a story that always employed the contrast between childlike art and harrowing events. Rather than Kyou’s innocent doodles, though, the anime uses mebachi’s cute designs and that Miyazaki-like bubbliness in the animation.

Above all else, this is a mind-blowing achievement from director, storyboarder, animation supervisor, and co-scriptwriter Yukimitsu Ina. He’s still a young artist himself, barely a few years removed from being mentored in Yukiyo Teramoto’s The Chronicles of Rebecca (2020). And yet, despite having no real experience with this stylistic register other than his participation in the aforementioned Natsuzora, he showed a deep understanding of Miyazaki’s animation tendencies and how to use them to evoke powerful feelings. In the end, the result isn’t as polished as a Ghibli work; it would be unreasonable to expect it to be, given its focus on the mentorship of youngsters. It does, however, feel like a very fitting angle for Cocoon to take due to the already existing link between Miyazaki’s work and the War. It’s borrowing not just a language but a context, and deploying it in a story that always employed the contrast between childlike art and harrowing events. Rather than Kyou’s innocent doodles, though, the anime uses mebachi’s cute designs and that Miyazaki-like bubbliness in the animation.

That contrast is at the core of its most impressive scene, which results in most of the students being killed. Unlike the manga’s unflinching depictions of massacres, the anime filters them through the fantasies that these children have to cling to when reality is just that cruel. Rather than blood splattering all over, we begin seeing death as fluttering petals— the idealization within the cocoon. However, it’s not as simple as the anime being a more starry-eyed version of the story. Its viewpoint also emphasizes the transformative aspect of the cocoon, giving the protagonist an arc about growing more resolute rather than surviving through untainted virtue. This emphasis on change is particularly interesting when it comes to her crush; in both versions of a story, born a boy to an affluent family that tried to dodge being drafted as a soldier through gender shenanigans, which allows further interpretations in an adaptation about being born anew. If you believe you can stomach these topics, I would recommend checking out both versions of the story to experience the noticeably different flavors.

Despite the generally positive feelings toward this project, we couldn’t finish this piece without addressing its nature as a training program—and sadly, not from a positive angle this time. I need to preface this by saying that personally, I’ve heard testimonies about not only this project but also other Sasayuri endeavors that painted a positive experience; in particular, about Tateno herself being accommodating to people’s personal circumstances. I don’t doubt those for a second, given that they came from trustworthy individuals who had no reason to misrepresent their own experience in that environment. However, it has become increasingly clear that theirs wasn’t necessarily a universal feeling.

That veterans with this Ghibli-adjacent background have high standards is neither surprising nor necessarily a bad thing; in fact, drilling the fundamentals you struggle to get elsewhere in the industry is the point of this effort to preserve traditional technique. That said, good intentions don’t excuse in any way that they would harass students in the way a certain animator reported at length. According to the person in question, verbal abuse and completely out-of-line accusations of mental illness would be hurled around regularly. As they speculate, this would be meant to demoralize and get rid of the students who couldn’t hit the ground running immediately, so they could focus on the more technically capable ones. As the discussion gained traction, other trustworthy voices in the industry didn’t hesitate to share similar accusations.

That veterans with this Ghibli-adjacent background have high standards is neither surprising nor necessarily a bad thing; in fact, drilling the fundamentals you struggle to get elsewhere in the industry is the point of this effort to preserve traditional technique. That said, good intentions don’t excuse in any way that they would harass students in the way a certain animator reported at length. According to the person in question, verbal abuse and completely out-of-line accusations of mental illness would be hurled around regularly. As they speculate, this would be meant to demoralize and get rid of the students who couldn’t hit the ground running immediately, so they could focus on the more technically capable ones. As the discussion gained traction, other trustworthy voices in the industry didn’t hesitate to share similar accusations.

It’s worth noting that the anecdote that sparked everything specifies that they were part of a studio that outsourced their douga training program to Sasayuri; a deal that they’ve established with the likes of WIT and BONES, and that immediately got muddied by the intervention of companies like Netflix who’d sponsor it but adding questionable exclusivity clauses. It’s entirely possible that this gap in experiences with Sasayuri comes down not just to technical skill as judged by the mentors, but also to whether it is one of the company’s own projects or these work-for-hire opportunities.

Regardless, the conclusion is the same: it’s never enough to act the right way often, even most of the time. Even if your goal is noble, it’s not worth traumatizing young prospects to the point where they don’t feel like drawing anymore. Ghibli themselves always cast, for a company that stood heads and shoulders above the practices of the industry as a whole, a dark shadow covering those artists who were crushed by their high standards. And if it’s already excessive to treat veterans in a certain way, it’s even more unacceptable to do it to students fresh out of school. Cocoon is a gorgeous film that preserves endangered techniques, using them to depict youngsters who must hide themselves from soul-crushing realities to try and survive. As viewers, though, we ought to face not just its beauty but the uncomfortable reality around it.

Honey Lemon Soda and Kiyotaka Ohata’s maddening brilliance

It’s hard to convey to younger viewers, for whom JC Staff is mostly a ruthless factory line outputting a dozen works a year, that it once was one of the most vibrant spaces in anime. And it’s even more complicated to get them to understand that this hasn’t involved driving away the standout talent from that era; many individuals who began shining alongside the likes of Kunihiko Ikuhara remain at the studio, entrusted with important roles as well. Unfortunately, the production system has warped the entire company and what those high responsibility roles entail. Shinya Hasegawa is as much of a legend as he ever was, but when his job is mostly to ensure that the drawings in often rushed productions are good enough, aspects like the lively acting he was known for become less prevalent. Some veterans don’t adapt well to the turning tides of the industry, while others simply decide to stop going overboard in the way you must if you want to shine in anime. Overall, however, the issue with JC Staff’s seemingly timid veterans is clearly systemic.

Few cases illustrate that better than Hiroshi Nishikiori, a greatly underrated director. Perhaps because of his adjacency to the stars of the caliber of Mamoru Hosoda or Ikuni himself in projects like Utena, he’s taken for granted and assumed to be a lesser contributor to such monumental works. And yet, those renowned creators are quick to praise his efficient ingenuity. Between the late 90s and early 00s in particular, Nishikiori was simply on a roll. He was the leader of hits like Azumanga Daioh, as well as an occasional (yet often a standout) contributor to other titles emblematic of that time like Orphen and Alien 9. No work sums up his effortlessly evocative imagery, quirky humor you can trace back to Junichi Sato, and the nets of relationships that sustained this post-Utena golden age better than Tenshi ni Narumon. As his series direction debut, for an original project at that, it’s the most undiluted showcase of Nishikiori’s appeal as a director—and of that whole era altogether, since the likes of Hosoda showed up to help. Sometimes, with quite a curious crew forming around it.

Few cases illustrate that better than Hiroshi Nishikiori, a greatly underrated director. Perhaps because of his adjacency to the stars of the caliber of Mamoru Hosoda or Ikuni himself in projects like Utena, he’s taken for granted and assumed to be a lesser contributor to such monumental works. And yet, those renowned creators are quick to praise his efficient ingenuity. Between the late 90s and early 00s in particular, Nishikiori was simply on a roll. He was the leader of hits like Azumanga Daioh, as well as an occasional (yet often a standout) contributor to other titles emblematic of that time like Orphen and Alien 9. No work sums up his effortlessly evocative imagery, quirky humor you can trace back to Junichi Sato, and the nets of relationships that sustained this post-Utena golden age better than Tenshi ni Narumon. As his series direction debut, for an original project at that, it’s the most undiluted showcase of Nishikiori’s appeal as a director—and of that whole era altogether, since the likes of Hosoda showed up to help. Sometimes, with quite a curious crew forming around it.

The spark from that time is sorely missing in Nishikiori’s modern output. Again, that mostly seems to come down to the industry and his home studio creating a different type of work at a different pace; feel free to replace that adjective with another, more negative word yourself. Even in this less favorable scenario, you can still get glimpses of that efficient charm every now and then. Just last year, he was entrusted with following up the grandest episode of Dandadan, which he accomplished with a funny enough storyboard that you wouldn’t stop to question the notably lower production values. It’s also worth pointing out that at no point has he become a bad director. The ceiling of Nishikiori’s titles is certainly lower nowadays, but the floor remains sturdy for as long as he’s not told to build a house on top of quicksand. In a way, that sums up that systemic JC Staff deterioration: very skilled veterans must be deployed for their reliability rather than their brilliance.

Why bring that up now, though? Well, 2025 started with an adaptation of Honey Lemon Soda led by Nishikiori which is… again, exactly fine. While I wouldn’t ask people to go out of their way to watch the anime if they’re not already interested, it’s a cute enough series about love as a vector of self-improvement and connection. His own episodes stand out somewhat because of the spacious camerawork; although it often demands the type of tricky drawing that a modest production like this struggles with, it also allows the series to draw a clear bridge between physical and emotional distance. Even without the series director swinging for the fences like he once did, those fundamentals can sustain the type of project that might have fallen apart at the seams otherwise.

In place of the series director, the individuals who can funnel ambition to productions like this tend to be the storyboarders and episode directors. #05 shows as much, as boarded by another JC Staff veteran from the same circle in Yoshiki Yamakawa; its higher degree of abstraction makes the daily life bits more evocative and even conduces to more playful animation. However, if there’s someone who takes their episodes to a level where they deserve a broad recommendation (especially to people with a taste for 90s anime), that is without a doubt Kiyotaka Ohata. At his best, he had been Nishikiori’s greatest ally—both in quantity and quality of their work together. From the greatest episodes of Azumanga and other highlights like its iconic opening to those more idiosyncratic, personal projects like Tenshi ni Narumon; Ohata was always there, and he always delivered.

In contrast to directors from similar circles who use repetition to establish a poetic cadence, Ohata employs it like fun percussion that sweeps you along. Repeating loops of animation, of surreal patterns and actions, of typography and colorful voids where everyone casts vibrant shadows. He’s in his element when the rhythm is high, and if a show isn’t careful enough, he might drag it in that direction with his aggressive framing. An approach with such a strong taste that it won’t suit everyone, yet one so distinct I’d miss even if I wasn’t a fan. Unfortunately, he has undergone an evolution similar to his friend Nishikiori. Rather than transitioning into a tamer series director (his experiences in that seat could have gone better), he has become a storyboarder by trade, lessening his involvement and not even putting himself in a position to push boundaries like he once did. His occasional openings are recognizable to this day—even a 3D show can look like Azumanga’s sibling for a second—but otherwise, that era of Ohata has mostly faded away.

In contrast to directors from similar circles who use repetition to establish a poetic cadence, Ohata employs it like fun percussion that sweeps you along. Repeating loops of animation, of surreal patterns and actions, of typography and colorful voids where everyone casts vibrant shadows. He’s in his element when the rhythm is high, and if a show isn’t careful enough, he might drag it in that direction with his aggressive framing. An approach with such a strong taste that it won’t suit everyone, yet one so distinct I’d miss even if I wasn’t a fan. Unfortunately, he has undergone an evolution similar to his friend Nishikiori. Rather than transitioning into a tamer series director (his experiences in that seat could have gone better), he has become a storyboarder by trade, lessening his involvement and not even putting himself in a position to push boundaries like he once did. His occasional openings are recognizable to this day—even a 3D show can look like Azumanga’s sibling for a second—but otherwise, that era of Ohata has mostly faded away.

There’s an easy way to illustrate his current situation: over the last decade, he’s only been in an position of control of an episode as the storyboarder and director 6 times. The upside to that statement, though, is that two of them were precisely in Honey Lemon Soda. His first scene in episode #06 is a statement of all the qualities we’ve summarized. There’s the evocative storyboarding, with the transition from a narrow window that traps the protagonist to a plane flying the open skies; the former, a representation of her timid life so far, the latter, of her desire to reach new destinations now that she’s reinvigorated by her love. The solid color silhouettes are straight out of his intros, and the rhythmic repetition (jump cuts, constantly overlapping panels) is somehow even more representative of Ohata’s style.

In spite of his rowdiness, Ohata’s approach proves to be rather atmospheric as well. His percussion can slow down just enough to establish a laid-back yet still lively rhythm, where both posing and voice acting synchronize to add to the musicality. The motifs (like traffic signs related to that personal growth) and recurring layouts give it a similarly rhyming structure on the macro level, which underlines how her group of friends is expanding in a natural way. And whenever he can get away with it, the comedic animation physically drags you a few decades back. Amusing multiplicity, a dance between different levels of artifice, and brilliant repurposing of the motifs he himself introduced. After an episode where the protagonist basks in the light for the first time, the moment when she’s knocked down brings her to darker places that only her love interest can seem to illuminate. Of all things, it’s the plane that represented her resolve that covers the sun and then flies away… with the perfect timing to make her appear like the dazzling one.

Ohata’s next appearance in episode #11 begins with equally recognizable rhythm and rules of cartooning; taking the latter even further this time, as he finds ways to insert typography and VFX with the full range of diegetic to proudly artificial. A couple of new wrinkles make it even more special, starting with the fact that one of the greatest animators of all time makes multiple guest appearances. Takeshi Honda had taken the world by surprise by showing his face (scarcely seen in TV anime nowadays) in the opening, but even then, no one would have expected one of the most renowned figures in theatrical animation to descend upon the show itself. The natural flutter of the fabric alone in mere practice shots are enough to tell that he’s a different breed altogether.

The second reason why this episode lands with even more impact is that it’s perhaps the most satisfying development in the relationship you’ve seen progress for nearly an entire cours. Honey Lemon Soda had been gesturing in the direction of a more even and reciprocal bond between its two leads, but it’s not until episode #11 that—through Ohata’s maddening sugar high—you see that materializing in slightly surreal, very cute ways. This culminates in another meeting between Honda’s unmatched form and Ohata’s flavorful direction; and also, a meeting between two highschoolers who have demonstrated they both can be relied upon. While the context makes moments like this much better, Ohata’s work in the show is good enough that I’d implore anyone to tune in for at the very least these two episodes. If you were into any of the works we mentioned earlier, or 90s to early 00s anime at all, it’ll be like meeting a dear old friend.

I had heard Tokio Igarashi was good, and Zenshuu #07 really showed that he is

From the opposite angle to rediscovering excellent veteran creators, there’s the equally rewarding feeling of finding out why an up-and-coming artist had been earning a positive reputation. It’s not as if I hadn’t ever seen the work of Tokio Igarashi before—most notably, he’d participated in the second season of Vinland Saga, which I found to be even more powerful than its predecessor. Despite having crossed paths before, though, it had never been meaningful enough for his input to register in my mind; it’s worth noting that he has only recently started drawing his own storyboards, despite having credits for cleaning up other people’s since around 2022.

Come 2025, I’ve finally had a chance to experience something that feels like it truly is an Igarashi episode. His contributions to Zenshuu arrived during the back end of the show, but later definitely doesn’t mean lesser in this case. Episode #07, which he directed and storyboarded, addresses key areas where the series had been lacking before. Most importantly, it does so in a compelling enough way that you’re not left feeling like they put a hasty band aid over an open wound. To put it in more specific terms: Igarashi’s delivery manages to humanize Zenshuu’s protagonist Natsuko Hirose, depicting a series of vignettes of the intersections between her life and those who have been touched by it.

Zenshuu‘s core staff also features some creators we’ve been talking about for the last decade. There’s series director Mitsue Yamazaki and her recurring assistant Sumie Noro, writer Kimiko Ueno, and of course everyone’s favorite designer Kayoko Ishikawa. If you thought we wouldn’t take this chance to share her iconic Aikatsu endings again, you’re so very wrong. The alternative would have been to cry about one of her buried projects with her friend Sayo Yamamoto instead.

Of course, it’s not as if stories have a duty to feature universally likable leads. We’re also not dealing with a case of a protagonist without a fundamentally compelling conflict; the creative block and expectations she leaves behind in the first episode are a solid starting point… however, she does indeed leave them behind, with the show only occasionally being able to underline how her current isekai life spells out an answer. Without much chemistry between her and the new cast either, you’re stuck with a protagonist that is presented as neither all that enjoyable to hang out with nor pointed in her distancing from others. That is, until episode #07 arrives, showing that she did have a charismatic creator personality at her core—one that explains why people gathered around her to create animation (and now, to save the world) better than her technical skill and fame do.

Each scenario showcases a slightly different side of her personality, as she grows up chasing her dream to become a virtuoso animator. Sure, she remains self-absorbed in a way that makes her current self still recognizably the same, but we see why Natsuko was such a magnetic individual as well. Again, it’s not because she’s good at drawing—the show already attempted to convey that before—but rather through her genuine, focused passion that touches others. The first love framing of its short stories adds to the inherent comedy of most of them, but don’t get that confused with an excess of irony; if anything, the episode shines in the way Igarashi’s direction unashamedly embraces the romanticized viewpoint that she shares with those drawn into her life. The second one in particular stands out, effectively operating like the type of honest, uncomplicated romantic short film that resonates all the same. There’s something to be said about storyboarding that proves to be imaginative and its framing and ambitious in the technique it demands, but so blunt in its emotional appeal.

Another aspect that stood out is the higher degree of refinement of the animation, which is not a quality that you naturally get out of a production system like MAPPA’s. They have an extraordinary ability to attract talent capable of outputting flashy work and have grown to a size that makes them able to finish work under any circumstances (not that Zenshuu itself was under such duress), but polish can’t be taken for granted when all the regular animation direction is sprinkled across dodgy SEA support companies. There’s no doubt that much of it comes down to the chief supervisors and their assistants—Masahiko Komino and Shuji Takahara on top of the regular Kazuko Hayakawa and Ishikawa herself—who certainly feel cherry-picked for an episode meant to be important. Additionally, that subtler quality sometimes trickles down to even the in-betweening; overseen by one of the team’s more trustworthy individuals, and with credits structured in a way that makes me wonder if they opted for more reliable paper douga in delicate spots.

Whichever trick there was between the more careful drawings managed, thanks to clear prioritization as well, to make the result feel much more palpable. This is an all-encompassing quality, which aids even its comedic scenes; you can only land a gag where someone’s shock is matched to their aging and wearing if you can make the drawings themselves a detailed embodiment of that idea. The effect of the delicacy in the expressions goes without saying, and just as important is the way that the entire theme of the work feels best represented. Even though Natsuko’s animation processes aren’t made made as grand as in the stock footage, the tactility whenever a shot is dedicated to the drawing process and the effort behind it feels realer than ever before.

Whichever trick there was between the more careful drawings managed, thanks to clear prioritization as well, to make the result feel much more palpable. This is an all-encompassing quality, which aids even its comedic scenes; you can only land a gag where someone’s shock is matched to their aging and wearing if you can make the drawings themselves a detailed embodiment of that idea. The effect of the delicacy in the expressions goes without saying, and just as important is the way that the entire theme of the work feels best represented. Even though Natsuko’s animation processes aren’t made made as grand as in the stock footage, the tactility whenever a shot is dedicated to the drawing process and the effort behind it feels realer than ever before.

Igarashi would later return with a storyboard for episode #09, this time under Sumie Noro’s direction. Its first half feels like the epilogue to #07; yet another vignette of someone crossing paths with Natsuko and witnessing the humanity hidden behind a lot of hair and grumpiness, which is enough to leave a heart-shaped mark in their life. In the end, however, it doesn’t feel like a special occasion like Igarashi’s previous offering—it’s not designed to be in the first place, as a storyboard-only job for him and a more rudimentary story beat. It was bold for the show to place such a load-bearing episode as late as it did, and I’m not entirely sure that it was the best decision. What I know, though, is that in and of itself it was an adorable way to express the message that love is mandatory for the creative process. I’m happy that I got to watch such a sweet episode by a director I now know to keep my eyes on.

The mandatory plea for people to watch more independent, alternative animation

I won’t be surprising anyone by noting that most people limit their view of anime and animation altogether to commercial works. While the ease of sharing videos online has made it much more likely for others to stumble upon music videos, student graduation projects, and all sorts of short films, those are but a fraction of the rich spectrum of non-commercial and independent animation. Many stunning, deeply resonating works are screened across international film festivals yet never shared in platforms that everyone has access to. There’s no understanding why viewers gravitate so strongly toward commercial works without accepting this fact.

For as uncomfortable as it makes some people to even consider the idea, there is some upside to that barrier of entry. To put it simply, we tend to engage with art that we seek proactively in a more involved way than those works that are so heavily promoted and entrenched in culture that we consume them almost passively; that’s the moment when creations become the dreaded word, content. While I can understand that point of view from a philosophical standpoint, however, I can’t subscribe to it as someone who enjoys sharing interesting works—and as someone who enjoys being able to watch them, for that matter.

Let’s put some names to this. Koji Yamamura is one of the most important figures in independent animation history, and yet I haven’t found a chance to watch his blend of prose and animation by the name of Extremely Short yet. Because of scheduling conflicts, in recent film festivals I’ve managed to miss it alongside First Line; technically part of a TOHO initiative yet following the alternative animation circuit, this short film by friend of the site China examines the act of creating animation itself. The same happened with Yoriko Mizushiri’s Ordinary Life, winner of a Silver Bear prize at the Berlinale 2025. Even if you pay attention to animation below its commercial surface, it’s not always easy to catch even the most renowned alternative offerings.

Mind you, this isn’t meant to be a discouraging story about the incredible effort required to watch indie animation—it’s the opposite, rather. There’s no denying that spotty distribution can make these titles more troublesome to access. Because of their irregular release patterns, they’re also stripped out of the window of public relevance awarded to commercial anime. And yet, their nature also makes them more prone to discoveries that feel personal. For all we’ve highlighted their limited availability, they will often get shared in quieter corners that are often just one search away.

This can be illustrated by returning to the previous anecdote: another short film I thought I had missed at a local festival was Nana Kawabata’s The Point of Permanence. Its trailer had caught my attention, and a bit of research indicated that I wasn’t alone; she’s been able to share morphing landscapes that feel like a deity peeking into humanity not just through plain animation, but in exhibits, installations, and books as well. While lamenting that I’d missed a chance to watch her work, I looked it up one more time and noticed two things: one, that she’d been nominated for the Asia Digital Award FUKUOKA, and two, that the site to showcase the winners features the actual works. Stumbling upon a channel that gets just about a dozen views while sharing gems that have limited availability is the type of rewarding experience you can get out of alternative animation, if you put just a bit of interest into it. Don’t be scared to give it a try!

Was Kawabata’s work worth the excitement, though? The answer is clear. The Point of Permanence challenges itself to simultaneously tell the story of the cells that compose a living being, of one individual, and of humanity as a whole. The lines between them are blurred; or rather, weren’t they hazy in the first place? At all levels, we organize ourselves in a similarly orderly fashion, requiring coordinated repetitive action for our collective growth. It’s no surprise, then, that the smallest units inside our bodies seem to have human silhouettes of their own—stylized into universally recognizable stickman figures. They pulsate endlessly, as they navigate systems that are reminiscent of both tiny snapshots of biology and history at large. The awe of life is delivered by instinctively satisfying visuals as clearly as its preoccupations about it become sound, growing more uncomfortable as everything expands and overlaps.

This short film’s triumphs are many and not particularly subtle. Above all else, Kawabata’s work impresses in the way it can stretch the exact same concept for slightly over 10 minutes. The enchanting morphing animation that had already caught my eye in trailers is what kept me glued to the screen for its entire runtime, constantly finding ways to iterate on that seemingly endless cycle. In that progression, you notice its ability to evoke scale and expansion; despite having no objective point of reference, and with drawings that already begin with a high degree of density, it still feels like it takes us from the microscopic to the infinite.

In the end, Kawabata doesn’t seem to interpret this eternal growth that we’ve historically sought (a biological tendency, given the parallels she draws?) as liberating, however. After so much advancement, development, and increases in complexity, the cell of humanity that felt so massive slowly fades into the distance. From this still point of view, it’s actually becoming smaller, trapped into an increasingly tiny dot that it can’t escape from—the point of permanence.

Just by checking out a few more offerings from those recent awards, one can find a few more interesting works; amusingly, that includes one with very similar traits to The Point of Permanence. HuaXu Yang’s Skinny World too draws parallels between the human body and society, specifically to cities, as two meticulously arranged systems of functions. Despite the complex imagery that gives form to those ideas, he’s able to evoke by subtraction and implication as well. This process results in a surprisingly amiable, surreal landscape that might leave you wondering if our society is merely replicating animalistic, fleshy behaviors. And if you’re not into this type of arthouse efforts that speak to the senses above all else, you can swing the other way around to Li Shuqin’s To the Moon and Back: an uncomplicated, honest story about processing grief at a point where you don’t quite know that feeling; only its pain, fresh and new.

It’s no surprise that many stories about loss are framed from the eyes of a child. It’s not simply due to those experiences being the ones that stick with us in the long run, but also because the lack of preconceptions about death allow us to explore it without the baggage that we inevitably accumulate later in life. It’s a vision of loss that doesn’t get diluted in thoughts about repercussions that we may not understand. And yet, it’s also materially tied to elements of that small world that surrounds us when we’re young, like a tadpole that we may have raised. What stood out the most about this short film was the creative choice to retain visible remnants of the previous frame when moving to the next one—an attempt to capture a feeling akin to paint-on-glass animation, which is also reminiscent of the marks left by the lives that have left us. Although not strictly autobiographical, it’s a very personal short film in a way that gets across clearly to the viewer.

If we started this corner by acknowledging the barriers of entry to independent animation on a material level, I want to let To the Moon and Back serve as an example that the idea that they’re inaccessible as art is silly. Inscrutable arthouse pieces do exist, and they can be an excellent way to free yourself from dogmatic beliefs about what storytelling should be like; and whether it’s even necessary to tell a story for art to be poignant, for that matter. But at the same time, many of these independent short films are simple, personal tales that resonate through honesty, that become memorable by choosing uniquely fitting styles and techniques that commercial animation would be afraid of. So leave those fears behind yourself and follow artists, keep an eye on festivals and specialized sites, or I don’t know, follow vtubers with a good eye for indie folks. That helps too.

Did you think those were all the animated works that stood out to us? Of course not

- Kusuriya no Hitorigoto / The Apothecary Diaries is fundamentally great in ways that should surprise no one now that we’re halfway through its second season. The source material lures you in with a charming cast, whose antics and episodic mysteries are later used to assemble overarching puzzles. Although the scriptwriting ought to be a bit more confident in spots—the dialogue sometimes goes out of its way to reiterate clues—the actual plotting is bold and always very satisfying in retrospect. Our coverage of the first season highlighted those qualities, as well as the understated system of success they built for all directors to shine. Although that remains true, reckless scheduling has caught up to it; a less extreme case than the issues My Happy Marriage has gone through, though similar in nature. Their attempts to smooth over the troublesome schedule by dragging in a capable studio like C-Station to produce one in three episodes past a certain point led to notable results at first, yet gradually less consistent as they too got stuck in a cycle of crunch. Please give them props though, they’ve done more for the series than the credits convey! Great show, solid team, somewhat held back by inexcusable planning.

- As many other people, Hunter x Hunter 2011 was the TV series that helped me discover Yoshihiro Kanno’s animation. Ever since then, I’ve been following his career on and off, even in the types of shows that you wouldn’t expect from his reputation. For as much as I encourage everyone to broaden their understanding of artists, though, there’s no denying that Kanno shines best in action anime. His timing is forceful, but especially when he’s storyboarding as well, his setpieces have palpable flow. He has a tendency to overwhelm the screen through 2DFX and debris overload akin to the work Nozomu Abe, despite their stylizations being nothing alike. For starters, rather than aiming for Abe’s more picturesque sense of awe, Kanno uses those effects to indicate aspects like directionality; both in an objective way (where do the blows come from?) and subjective ones (how can we use elements like the direction of the rain to indicate a power imbalance?). This is all to say that I’m glad Solo Leveling fans seem to have realized how lucky they are to have him as an action director, because he deserves all the flowers.

- Although I was reluctant to get around to the third season of Re:Zero when it originally began its broadcast for reasons that now go without saying, I finally binged it in time to watch the final episodes as they aired. The series is in no position to compete with the seamless, immersive quality of the first season’s production, and having replaced series director Masaharu Watanabe also makes it struggle to reach the same heights of catharsis for its character beats—he operated on a different level of ambition. Although this results in a bit of a lesser season, I wouldn’t point at the new team (especially not with Haruka Sagawa as the new designer) so much as the arc itself being inherently less resonating; rather obviously so when its grand speech echoes one that carried more weight. It is, however, consistently entertaining to see every volcanic character in its world locked inside the same city after an exposition-heavy season. While Vincent Chansard’s transcendental draftsmanship understandably got the most applause, I’d point to Hamil’s constant appearances and the Archbishop of Lust’s morphing animation as the MVPs. The sequences where she unnaturally regenerates her body are not only technically impressive, but as unpleasant as she ought to be.

- While I didn’t get around to finishing the show, shout out to Shin Itagaki for his work on Okitsura. I’m not exactly surprised that his reputation among people who aren’t really in the know (or at least aware of his full resume) doesn’t match his ability, and a strangely crafted piece of Okinawa propaganda certainly won’t change that. All that said, I’m always happy to appreciate his work; the circumstances that surround him, though, not so much. His Teekyuu tenure proved that he could take the snappy timing that characterized his animation to the extreme, using posing alone to create an economical masterpiece. However, his eccentric artist blood has constantly pushed him in other directions. Even without citing the most controversial project he was tied to, shows like Kumo desu ga, Nani ka? showcased the type of volumetric ambition that a team like theirs simply couldn’t aspire to without crumbling… which is exactly what happened. Okitsura feels almost like an answer to that: occasionally built upon intricate character arc and bold framing, but willing to abbreviate the movement in classically Itagaki ways. In multiple ways, a romcom not quite like anything else.

- SK8 Extra Part was finally released a while back, living up to the promise of fun vignettes for the cast. Separated from the first season’s overarching narrative (though hinting at the direction that the sequel’s plot will likely take), those daily life moments range from worthy of a chuckle to very cute. While the ridiculous energy of the original show was its greatest asset, this OVA proves that some relationships have charming enough chemistry to still work in a more low-key situation. Here’s hoping that season 2 lives up to its predecessors, and that Hiroko Utsumi’s friends can show up like they did here.

- If you’ve been enjoying the combination of Gosho Aoyama‘s work with irreverent, Kanada-leaning animation in YAIBA, I’d strongly recommend watching episode #1155 of Detective Conan. Don’t let that large number scare you: it’s an original, ridiculous gag episode built entirely around the style of Hiroaki Takagi. Neither he nor the ex-Wanpack artists he surrounds himself with are newcomers to the series, but they rarely can go on a rampage with all limiters off in the way they did. The likes of Toshiyuki Sato appeared in the same way they’re doing for YAIBA; unsurprisingly, given that they both offer the possibility to have fun with pose-centric, loose animation. Convergent evolution within Aoyama series, I suppose. A good kind!

- Otona Precure—a series of spinoffs for the franchise both aimed and featuring adults—has been a mixed experiment. For its undeniable issues, ranging from certain Precure tropes feeling extraneous in this context to a subpar production, the 2023 series Kibou no Chikara was ambitious as well as angry in amusing ways. While I can’t say the same thing about Mirai Days, as it was a more straightforward sequel to Mahoutsukai Precure without much to state, it allowed Yuu Yoshiyama to go more ballistic than ever in the franchise. As the lead animator with a hand in every single highlight, be it from intervening in every step of the process to becoming a link with very interesting guest animators, Yoshiyama elevated Mirai Days’ experience way above what you’d expect from it on paper. What would happen if the Precure grew older? Kibou no Chikara’s answer was about time, the changes in our planet, and adult preoccupations. Yoshiyama delivers a more straightforward answer: they would punch damn hard, because magical girls are cool as hell sometimes.

- Since we published a lengthy piece about Kenji Nakamura’s entire career not long ago, I didn’t feel the need to talk about the Mononoke movies again; especially not given that they’re meant to be a trilogy which is yet to be completed. That said, the second film led by Nakamura and his right-hand man Kiyotaka Suzuki was recently released in theaters, so I simply want to issue the periodic reminder that you should check out the series. As unique as commercial anime gets, and by comparing each instance of it, a fascinating illustration of Nakamura’s constant evolution.

This has been quite the multi-part marathon about animation we published today, so we’ll be wrapping up here. And remember, if a work that resonated with you strongly wasn’t mentioned here, that must be considered a personal attack that invalidates you and the personality you wrote around a piece of fiction. Or perhaps that’s not how it works and fandom spaces are poisonous, who can tell! For as many things we try to keep track of with a rather omnivorous diet, it’s impossible to watch everything—and it would simply be disingenuous to fake interest in works that haven’t piqued our curiosity.

As always though, feel free to ask about anything else… unless it’s about a certain famous fighter who recently became a kid (again) or a group of dramatic girls who confused bands for therapists, since there are already drafts written for those. I didn’t go insane watching Ave Mujica just to bottle up those feelings, even if that would be very in-character for the series.

I know I said I would leave the raving about Ave Mujica for another day, but can you believe that one of the outstanding music videos they released during its broadcast was produced by Saho Nanjo’s usual team? Featuring the likes of Setsuka Kawahara in charge of the watercolor and sand animation, Haruka Teramoto in charge of the CG and photogrammetry, Kana Shmizu for its photomontages of nightmarish longing hands. Just a few months ago, I pointed at them as one of my coolest creator discoveries in recent times, and here they are in the (so far) series I’ve enjoyed the most in 2025. Nanjo & co have the radical edge (and unconventional choices of technique) you’d associate with avant-garde animation, but also the ability to adapt and capture specific moots that makes them a viable option for commercial, narrative works. They sublimated the band’s gothic aesthetic and the fact that these girls are often more emotion than person into an incredible expressionistic work of animation.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!