Apologies for the delay with this post! Right after the audio episode went live, I had to turn my attention to a time-sensitive funding application. I appreciate your patience. Enjoy reading!

And so it ends.

In the final episode of The Origins of Humankind, we explore the aftermath of the story so far—the story of how one peculiar species, Homo sapiens, evolved, spread, and outlived its relatives.

Guiding us through this final chapter is Johannes Krause, the director of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology. Together, we uncover the emerging picture of the global spread of farming, pastoralism, and other key ingredients of modernity. Along the way, we explore some of the central questions of history—from the origins of inequality to the surprisingly pivotal role played by the peoples of the Eurasian steppe. (Yes, Mongols will make an appearance! But the story of the steppe goes much deeper…)

You can either listen to the full episode below or keep scrolling to read the highlights. For a more serious read, get a copy of Krause’s new book: Hubris — The Rise and Fall of Humanity.

Listen (1h03): Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Other players

This episode is part of the five-part series, The Origins of Humankind, produced together with UC San Diego’s Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny. You can enjoy each episode on its of head to the start here.

A New Era Begins — But Why?

Around 12,000 years ago, something strange happened. Farming appeared—and not just in one place, but in several unrelated regions. First, barley and wheat were domesticated in the Middle East. Rice followed suit in China. Millet and yams were soon domesticated in Africa, potatoes in the Andes, and squash and beans in Mesoamerica.

This cascade of events is surprising. In Krause’s words:

“It had not happen in 7 million years. We didn’t domesticate anything as far as we know. Then suddenly everywhere in the world people are doing the same thing.”

Yes, the origins of agriculture coincide with the end of the Pleistocene “Ice Ages”. This is the textbook explanation for its sudden appearance. But it’s not as if the Ice Age had made farming impossible before. Even during glacial times, the tropics remained warm. So why hadn’t anyone farmed there?

I asked Krause what he thinks of my the theory of Andrea Matranga, a previous guest, who thinks that farming was a response to a new kind of climate challenge: Compared to the Ice Ages, the new “Holocene” weathers were warm, wet, and relatively predictable each year—this much was benign—but the differences between seasons grew larger and larger. As Matranga explained it to me:

“Hunter-gatherers could gorge themselves during the hot rainy summers, but they risked starving in the harsh winters.”

Seasonality put a premium on food storage. Storing food led to settling down. And settling down paved the way to farming. As Matranga points out, areas with low seasonality, such as Australia, were precisely the places where agriculture never emerged.

Krause nodded in agreement, but maintained that this probably wasn’t the full explanation. He said the sudden appearance is so striking that it might require a biological explanation, too, perhaps even a genetic mutation. At the same time, he noted that such a mutation would have to be much older than farming, as it was carried by both Africans and non-Africans, separated by the epic Out of Africa event a bit less than 50,000 years ago. Maybe population pressure? Possibly so. But in the end, Krause leaned toward a simple but humbling conclusion: the rise of farming remains a mystery.

Less mysterious is what happened next: farming spread like wildfire.

Growing Farmlands

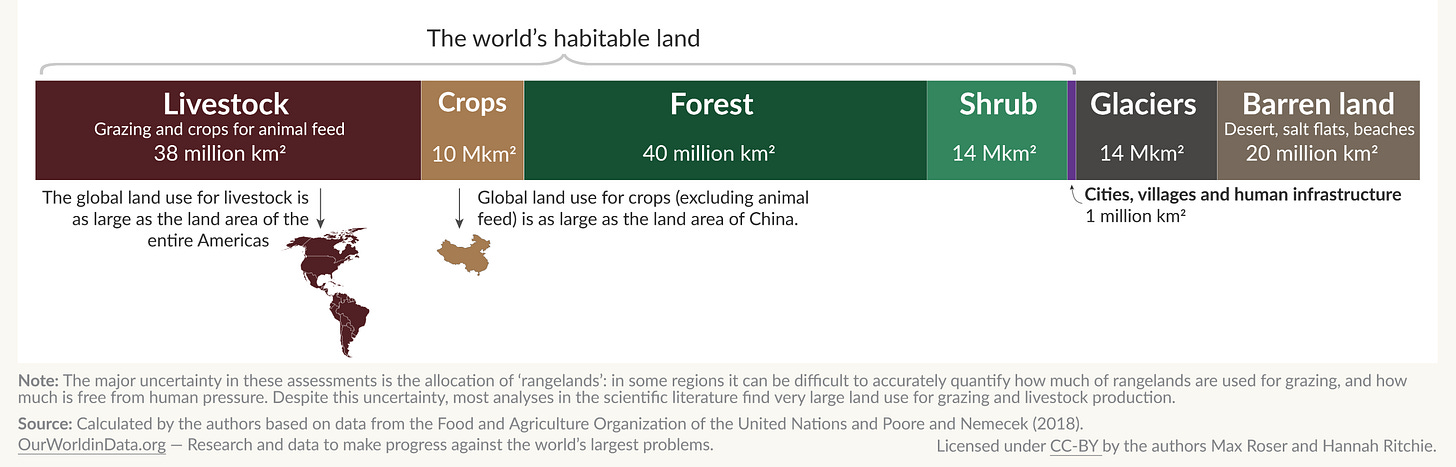

Why did farming spread so fast? This is no trifle of a question. From a planetary perspective, the story of the last 10 thousand years can be summarised into two words: growing farmlands.

Today, farming occupies a gigantic amount of land: around half of all habitable soil.

The spread of farming has been accelerated by modernity. But farming has always an expansive industry. Why?

For decades, the answer to this question remained something of a Holy Grail amongst pre-historians. Did farming spread as an idea, adopted by hunter-gatherers with farming fever? Or did farmers push into new areas, encroaching on the lands and hunting grounds of persistent foragers?

This question has been mostly settled. It has been done thanks to the ancient DNA revolution. Indeed, Krause and other archaeogenetists have shown that, time and time again, farming spread with farmers.

There are exceptions to this rule. The most important one is America, where the farming seems to have spread as a cultural “meme”, often adopted by neighbouring peoples who maintain some parts of their forager lifestyle. (Indeed, the scarcity of domesticated animals led most American farmers to be “hunter-farmers” rather than full-time agriculturalists.) Krause also explained that ancient North African foragers transitioned to herding when cows were introduced to the then-green Sahara.

But exceptions aside, the overwhelming trend is that early farming spread with farmers.

“It’s not necessarily people wanting to move to a ‘nice place with all this beautiful forests’. It’s just that people have a farm, they have five kids, and there’s not enough space on the farm.”

So why did farmers have more kids? We don’t quite know. Maybe crops made weaning easier. Maybe settled life eased the burden of childcare. But whatever the reason, the outcome is plain and clear: families grew faster than yields. Many young adults had to leave their parents’ farms. In theory, the unlucky children could return to foraging. But they didn’t have the know-how or the know-who. Most of them searched for more land.

Farmlands grew.

The same story unfolded on continent after continent. From the Middle East, generations of farmers pushed to Europe and North Africa. From southern China, farmers speaking various languages spread south towards Vietnam and east into the Pacific. On the ocean front, these oceanic farmers launched one of the most epic adventures in world history. They crafted canoes big enough to carry their pigs, seeds, and hoes with them. The waves were big, but so was the farmer’s imperative to find new lands. Taiwan came first. But the family’s kept growing and growing, and the island soon filled again. As before, some youngsters had to pack their canoes.

Eventually, these ocean farmers spread from Hawai’i to New Zealand and from Southeast Asia to Madagascar. Some islands were uninhabited by humans and awaiting discovery. Thus, humanity claimed some of the last remaining pockets of uncontacted land. On other islands, they met with native hunter-gatherers, sometimes even returning to the original economy. But with time, more and more of the Pacific islands became farmlands. Thus was born the Austronesian language family, connecting the Samoans and Tongans to Indigenous communities in Taiwan and Madagascar.

A similar story happened in western Africa, where farmers had domesticated yams, palms, and an African variety of rice. Boats played no great part here, as the farmers moved on foot. But as before, the thirst for land led to the birth of one’s modern world’s great language families: the Bantu languages, spoken across most of sub-Saharan Africa, from Cameroon to Kenya and from Tanzania to South Africa.

With the rising farmlands, humanity itself kept growing. Around the dawn of farming, our species had an estimated 4 million specimens to show for our success. Around the year zero, the estimated figure had climbed towards a third of a billion.

However, as humanity grew in size, humans themselves became smaller. Farmers had more stable diets in terms of average calories, but they lacked many essential micronutrients. Pharmacy supplements did not support their mostly vegetarian lifestyles, and they suffered from many deficiencies. In northern latitudes, their skins grew paler to soak up all the vitamin D the sun could give. Even this wasn’t enough to sustain the modicum of health hunter-gatherers had managed to maintain. Around the world, farmers were shorter and in worse health.

Poorer health was the main reason Jared Diamond asked if agriculture could have been “the worst mistake in the history of the human race”. But health wasn’t the only reason. Diamond also saw farming as a highway to inequality. Krause agreed:

“Almost throughout all of the Neolithic, we see something we call patrilocality: we have male lineages with a founding father and his sons and his grandsons — but all the females are coming from other communities. So the men stay and the women come in. If there is some kind of “birth of inequality”, then that’s it, because hunter gatherer societies today, and probably in the past, are pretty much egalitarian.”

Krause’s thoughts here echo those of my past guest, Angarika Deb. But Krause added a twist to the story: these Neolithic villages were patrilocal, yes, but monogamous.

“They were nuclear families.”

The era of powerful men gathering large harems was still in the future. But that future was approaching. When did it become the present? We don’t know. But it might have something to do with farming’s forgotten twin: pastoralism.

The Forgotten Twin

Farming wasn’t the only novelty in the human story. While most history books focus on grain-fed cities, a large chunk of recent history has been powered by a much less appetising energy source: grass.

Humans can’t eat grass. But cows, horses, and goats can. In pastoral life, these tame beasts act as conversion machines—turning grass into rich packets of milk and meat, and in the case of horses, into explosive power.

To the untrained eye, herders might look like hunter-gatherers: they, too, stay on the move, roaming the “wilderness.” However, like farmers, pastoralists produce their own food and store it for future use. Their storage, however, moves on four legs. Every day, they risk losing it all.

The constant risk of theft might be one reason pastoralists earned a reputation as fierce fighters—fierce enough to justify the construction of the Great Wall.

More broadly, a society that prizes fighting prowess tends to be one where men hold the upper hand. As Tamim Ansary writes in his altogether brilliant The Invention of Yesterday:

“Generals had to have brains. But brainiest once filled their front-lines with brawn. generals stack their front lines with big and strong soldiers. And men were generally bigger and stronger than women.”

In short, life on the steppe was hardly easy for women. If farming kickstarted a walk toward patriarchy, pastoralism turned that walk into a horse race. As Krause explained:

“We have in the Bronze age suddenly whole bands of people with the same Y-chromosome of some founding fathers of those steppe populations that start expanding around 5,000 years ago.”

It’s worth pausing here briefly. Our compressed overview couldn’t quite do justice to the magnitude of the event Krause describes here. I know many listeners might have been lost. So let’s unpack this.

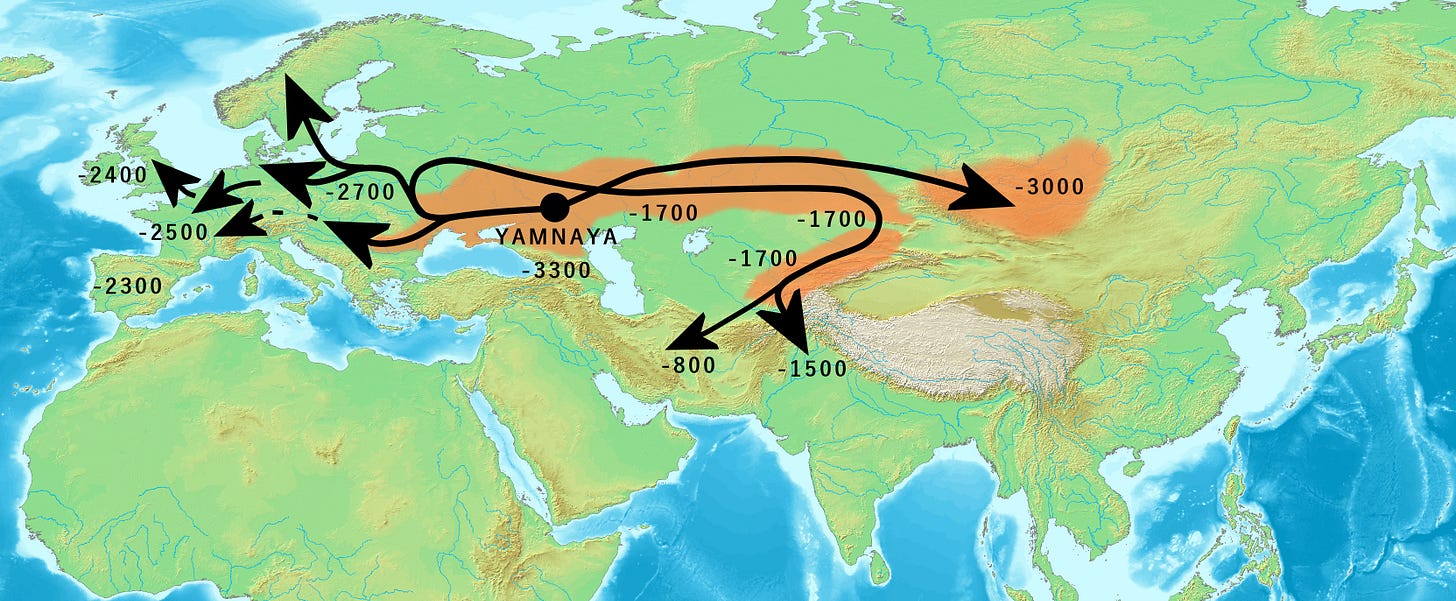

The steppe is a vast corridor of grasslands stretching from Ukraine to Mongolia and northwestern China—an “ocean of grass,” as Krause called it.

It was the birthplace of the Mongols, the Huns, and other famous horse-riding “barbarians” that Eurasian city-dwellers so often loathed. And around 5,000 years ago, something happened that sent steppe societies—and their gender norms—roaring across Eurasia. This “something” has become known to us only during the last decade or so, thanks to a mix of old linguistics with cutting-edge genetics. In Krause’s words:

“It’s probably also the biggest contribution of genetics to prehistory.”

So here’s the story:

Five thousand years ago, groups of nomadic pastoralists lived on the Western edges of the steppe, in what is now Russia and Ukraine. They settled near rivers, as humans must drink, and the steppe is dry. But things were changing. The wheel had just been invented—probably by these very people. Wheeled wagons, hitched to herd animals, allowed them to pack water supplies and leave the river valleys. Around the same time, horses were domesticated. The precise sequence is still debated.1 But one thing is clear: pastoralists from the western steppe began moving fast, across vast swaths of Eurasia.

In the west, they pushed across Europe, all the way to the British Isles, where Stonehenge was still being built. In the southeast, they crossed the mountains guarding India, a subcontinent where their reverence for cows persists to this day. In the south, they moved into the rocky hills of Persia, where their horse-riding skills paved the way for the world’s first mega-empire.

Wherever they went, these pastoral migrants carried their language. From their many dialects emerged the Indo-European family, linking Sanskrit to Spanish, and Farsi to Irish. They likely carried their gods too, which might explain the striking parallels between Hindu, Greek, and Norse mythologies.

As anyone familiar with Zeus’s sexual ethics can attest, these were myths told by tough guys—men who hardly regarded women as their equals. Indeed, the Indo-European migration was largely a migration of male gangs. This is surprisingly easy to read in the Y chromosome, which passes only from father to son. The pattern is stark. In Spain and Portugal, for example, just 200 years after their arrival, the population had about 40% steppe ancestry in their overall DNA. On the male line, the number climbs towards 100%. The Indo-European expansion was overwhelmingly a male expansion. (A similar pattern appears in Latin America, where paternal Y-chromosomes lean European, contrasting with the Indigenous ancestry in much of the maternal genes, found in the mitochondria.)

It’s impossible to know the details of these ancient events. Some scholars have warned against portraying the Indo-Europeans as simple genocidal warlords. They didn’t arrive in a single burst, but over centuries. And they were rarely buried with fighting weapons.

Yet it seems unlikely, to say the least, that these newly arrived men advanced women’s rights. These were, after all, men bound together by shared grandfathers, shared language, and shared stories of hyper-masculine gods. Indeed, the Indo-European expansion aligns precisely with the once-mysterious “Y-chromosome bottleneck”—a chilling moment in human history, when a select group of patriarchs began to dominate the genetic legacy of vast chunks of humanity.2

Indo-European migrations were the first time the people of the steppe played the leading role on the world historic stage. But it wasn’t the last. From Attila the Hun to the Mongol Empire, steppe pastoralism has often served as an engine of Eurasian history. Just look at the five great land empires of the early modern era: Safavid Persia, Mughal India, Ottoman Turkey, and Qing China, all of which trace their origins to the “ocean of grass,” where horses and cows served as substitutes for canoes and caravels. The fifth one—Russia—emerged as a project to defend its farming core against raids from the steppe.3

The steppe also gave us the horses—beautiful creatures, yes, but most influential as a tool of war.

“Horses completely changed warfare. They were like early tanks.”

Indeed, this was true across much of the Old World, from China to Mali. And when Spanish ships crossed the Atlantic, the Americas would feel the devastating impact that even small cavalry forces could unleash.

The lesson? Focus on farming at your own peril. More often than not, it has been herders, shepherds, and ancient cowboys who shaped history. And that would be true even without mentioning the desert herders of the Middle East, whose ancient culture was evolving into the languages and symbols used by Abraham, Jesus, and Muhammad.

No More Frontiers

Where does this leave us? Krause was not inclined to romanticise the past over recent industrial times. Instead, he noted that much of the human past has been expansive. From the Bantu to the Indo-Europeans, humans have been migrating to new lands and territories, discovering new resources to support their expanding families. Today, such frontiers are rapidly vanishing.

“We will never live in space. The space is a deadly space”

I’m inclined to agree: No amount of climate havoc will make the Earth less habitable than Mars. But what’s the solution then? Krause didn’t pretend to know the answer. But we must change our ways, he said.

“There are good signs. Everyone talks about sustainability.”

Whether that’s enough remains to be seen. Yet one thing seems increasingly clear: the second chapter in the story of Sapiens has come to an end. The third chapter has begun.

What a time to be alive.

This concludes the Origins of Humankind. During the past five weeks, we have covered everything from the origin of fife to the rise and spread of Homo sapiens. It’s been a tremendous journey. Thank you for reading. Stay tuned for more adventures to come!

These debates get tricky fast, requiring distinctions between related steppe populations like the Yamnaya and the Sintashta. For the purposes of this overview, I’m happy to condense them under the label of “certain pastoralists.” Whatever the fate of the finer details, one fact remains clear: wherever the action was, Yamnaya ancestry and Indo-European languages were never far behind.

I had not made the link between the Y-chromosome bottleneck and the Indo-European expansion. Oddly enough, neither have many others. Just Google “y-chromosome bottleneck Indo-European” and see the scarcity of explicit claims. Krause made strong hints at a link between the two, but didn’t go as far as to say that they are identical events.

I’ve spent a fair amount of time researching this after our conversation. My current hypothesis: They are the same thing. Prove me wrong!

Curiously, the rise of European maritime powers might also be linked to the steppe pastoralism. Maritime Europe emerged from small competitive states, where one monarch’s mistakes were matched by another’s successful gamble. This is a familiar story. Less familiar to lay people is Victor Lieberman’s increasingly popular hypothesis, according to which European fragmentation was enabled by their geographic “protection” from the steppe.