Ellen Swallow Richards (1842-1911) was a pioneering environmental chemist, ecologist, and perforce a feminist, because she dared to want to pursue a career in science at a time when women were generally not welcome in higher institutions of learning.

She was sickly as a young girl, and so was home-schooled by her parents. When she was 24, she learned of a new school, Vassar College, founded to grant degrees of higher education to women. She worked multiple jobs to earn the first year’s tuition, and at age 26, she matriculated, writing, as the author reports, “I am delighted even beyond expectations.”

She was able to continue studying at Vassar by earning scholarships and by tutoring other students. A class in applied chemistry convinced her that field was her destiny, but no chemical companies would hire a woman. She therefore sought to increase her knowledge at MIT, where every student was a male:

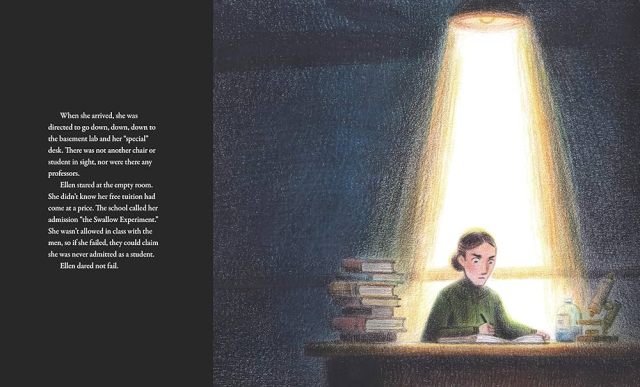

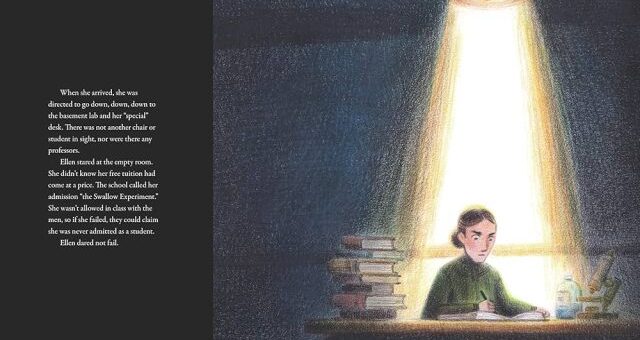

“Ellen didn’t care. She applied anyway and got in – with a full scholarship! At twenty-eight years old, Ellen Henrietta Swallow was about to become the first female student to step through the doors of MIT.”

Alas, she did have to study by herself in the basement, with professors sliding lessons for her under the door and picking them up the next day. After a year, she impressed her professors so much they let her into the classroom.

(She later learned that MIT did not charge her tuition so the president could say she was not a student, “should any of the trustees or students make a fuss about [her] presence,” per a Massachusetts history site on Ellen.)

The “Mass Moment” history site further reports:

“She received a BS from M.I.T in 1873 and continued her studies at the Institute for another two years. She never received the doctorate she hoped for reportedly because ‘the heads of the department did not wish a woman to receive the first D.S. in chemistry.’ While this was a deep disappointment (and a great injustice), the lack of a PhD. did not prove to be much of a hindrance to Ellen Swallow Richards in her work.”

An MIT professor asked Ellen to assist with a water survey for the city of Boston to identify which waterways were toxic, and she tested some twenty thousand samples, proving which rivers and streams were polluted and which were clean. Daniele informs us:

“Even before she graduated from MIT, Ellen became one of the world’s renowned water analysts. After she completed a second groundbreaking study, Massachusetts built the first water treatment plant, and the number of deaths of children and their family members went down.”

Ellen then moved on to analyzing food for contamination, pressing for change: “Massachusetts eventually passed the first pure food laws in the country.”

The President of MIT, 1971-1980 wrote: “She was among the first to realize the necessity for technology to counteract its own effects.”

The book ends on that note, followed by a timeline, Author’s Note, source notes, and a selected bibliography.

One item in the Author’s Note is especially worth noting. In it we find out that Ellen opened the Women’s Laboratory at MIT in a run-down garage called “the dump.” She taught classes there for no pay and raised money for supplies and equipment. Daniele notes that “seven years and five hundred students later, the lab closed when MIT became officially coed.”

Junyi Wu illustrates the story with textured color pencil pictures.

Evaluation: Talk about persistence! Both the recommended audience of 7 and up and adults who read the book also (for truly, there is a dearth of knowledge about women achievers at all age levels) will be astounded at what Ellen Swallow had to put up with and what she achieved in spite of it.

Rating: 4/5

Published by MIT Kids Press, an imprint of Candlewick Press, 2025

Nota Bene: The MIT Alumni Site has a nice list of some of her other achievements:

In 1876 she began teaching a correspondence course for women by sending them microscopes, specimens, and lessons to examine their home environments.

She founded a group supporting women’s education in 1882; that group grew into today’s American Association of University Women.

She helped to found a marine biology laboratory that grew into what is now the University of Chicago’s Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

She wrote or co-authored 18 books from academic texts to manuals on the chemistry of cooking for housewives and founded the popular American Kitchen Magazine.

Her 1878-79 studies of adulterated foods revealed mahogany sawdust masquerading as cinnamon and sand in sugar; her findings prompted the state to pass its first food and drug safety acts.

In 1890, she pioneered the New England Kitchen, a scientific take-out restaurant designed to feed nutritious and inexpensive food to the poor. That led to a similar demo kitchen in the 1894 World’s Fair and the revamping of the Boston Public School lunch program.

To build consensus and clarity in the new field of home science, Richards established an annual conference in 1899. That group, which developed curricula and teacher training, became the American Home Economics Association in 1908 with Richards as president.