Do you believe in love at first sight? Not the teenage crush kind—fleeting and hormonal—but a powerful, soul-stirring moment when you lock eyes with something or someone and instantly know: This changes everything. For Jim McVicker, that moment came at age 21.

He was casually flipping through his girlfriend Missy Vivenzio’s History of Western Art book when he stumbled upon landscapes of Monet and Pissarro. “I thought, ‘Oh, my God. What is this? I have never seen something like this before.’ When I saw those French Impressionist paintings, I felt like somebody was telling me, ‘Hey, this is what you’re supposed to do with your life.’”

Until that point, Jim had never set foot in an art museum and had barely given art a second thought. Driven by curiosity and passion, he enrolled in art classes at Chaffey College, a community college in Southern California. He copied Impressionist paintings as an educational exercise, starting with a Toulouse-Lautrec painting, The Clownesse Cha-U-Kao at the Moulin Rouge. By 1975 he was painting landscapes outside. To his parents’ dismay, he left school and quit his job to pursue painting full time.

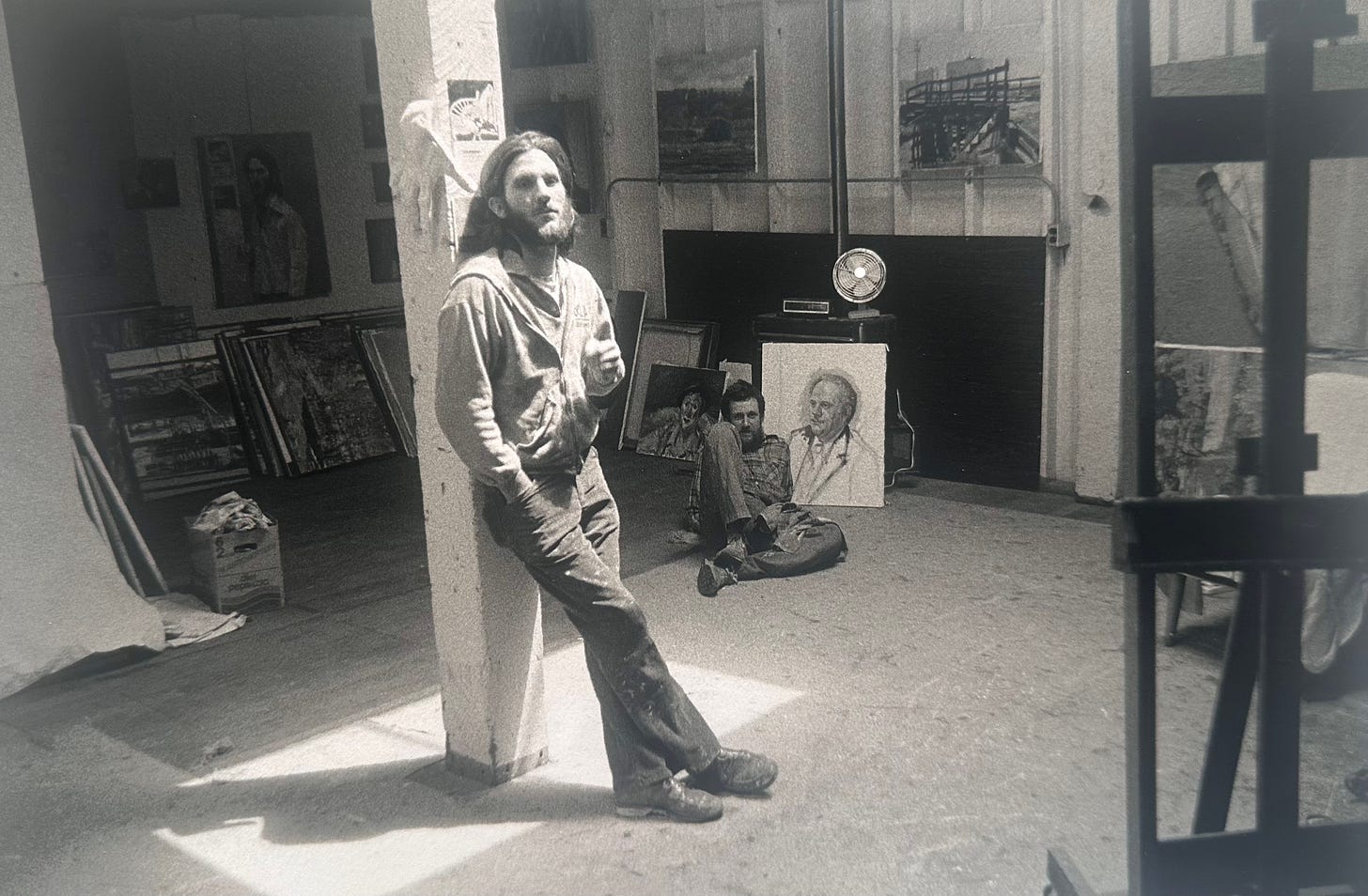

Around that time, he met expressionist painter Jim Gandee, who became a lifelong friend and influence. “I had never been into an artist’s studio before. When I entered Jim’s house, I saw paintings everywhere. I thought, ‘Wow, this is what an artist does.’”

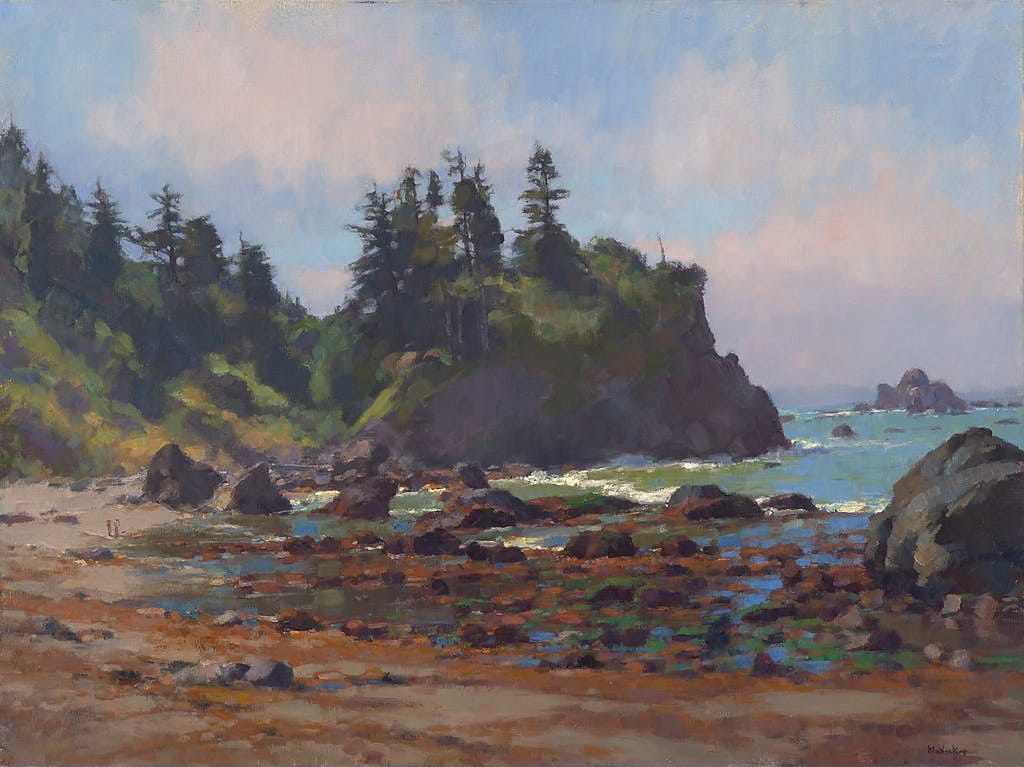

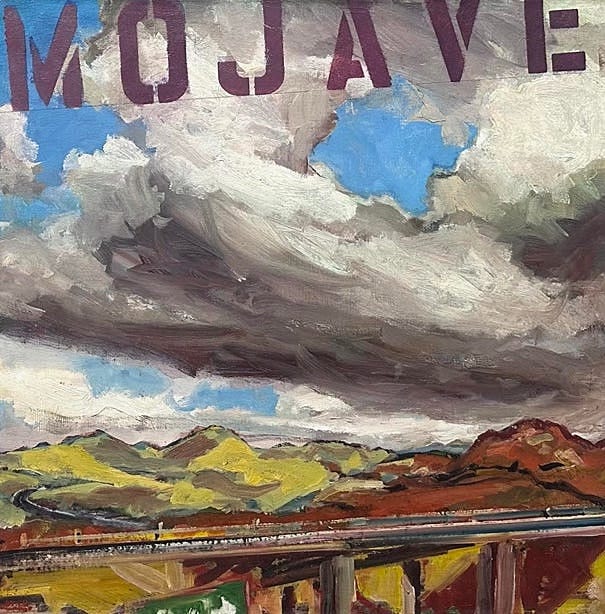

Seeking a change of scenery from his suburban Los Angeles surroundings, Jim moved up the California coast to Santa Cruz. He became interested in abstract painting after seeing the film Painters Painting and explored that for about a year and a half, painting every day. After visiting a friend in Eureka and discovering its vibrant art scene, he relocated there and returned to landscapes and painting from life.

Choosing to join a life drawing group was transformative. It was there he met painters George Van Hook, Curtis Otto, and James B. Moore. They invited Jim to paint with them. The opportunity to observe them at work was formative and sounded like a lot of fun to him.

Reflecting, Jim describes his early years this way: “I never looked at how-to books on painting. I didn’t go to an art school. I went to a community college, and there were three artist teachers that I worked with who were very good artists. But at the time, in the early ’70s, nobody was teaching how to paint, how to mix color, how to draw. They did encourage me to go outdoors to paint after they saw my landscape copies. I learned working around other artists. I always say you’re much better off working around artists better than you.”

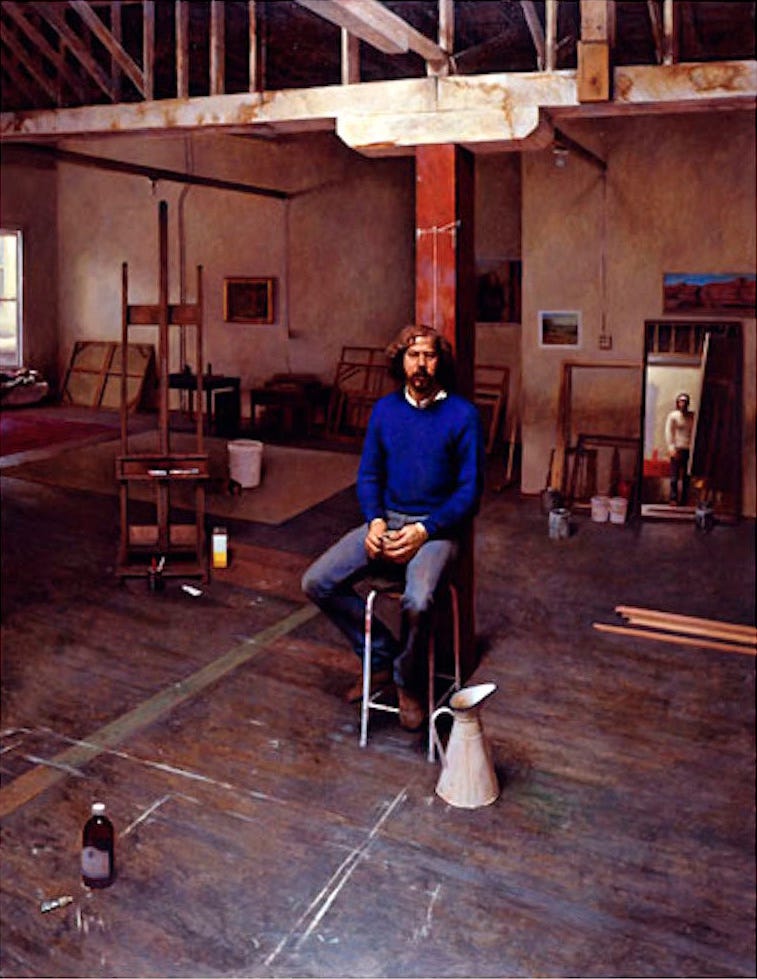

Jim continued producing landscapes, portraits, and still lifes. He married Terry Oats, also a painter, and they eventually built side-by-side studios at their home in Loleta, CA. Soon enough, Jim’s work was being shown in prestigious San Francisco galleries. Today, it continues to receive awards and recognition.

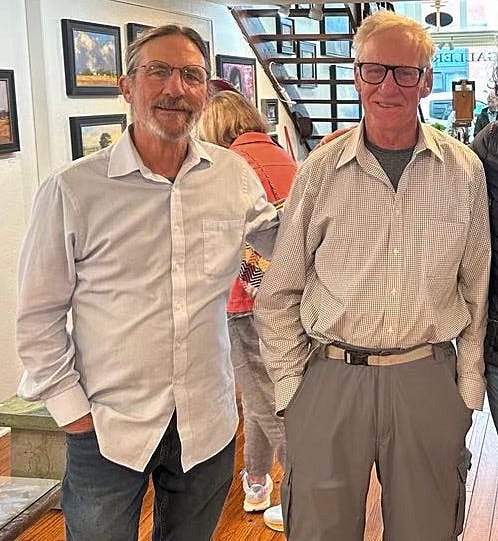

I first learned about Jim when I visited George Van Hook’s studio. George enthusiastically told me about his and Jim’s formative years painting together in Humboldt. I knew I wanted to interview Jim at some point.

Documentary filmmaker Petter Granrud was so impressed by Jim’s art that he made Jim McVicker: A Way of Seeing. The 2008 film follows Jim as he paints coastal and mountain landscapes around his Northern California home. A segment shows Jim working rapidly on a sizable still life piece in his studio. While the setup of a table draped with a decorative cloth, accompanied by a chair and some plants, might seem unremarkable at first glance, the painting in progress was anything but. I’ll just say I am a fan.

Here’s our April conversation conducted via Zoom, with Jim sitting in his spacious and softly lit studio. I would have liked to visit Jim’s studio in person and admire his magnificent paintings up close, but a trip to Loleta, CA, was not on the near horizon. During our chat I could see the space brimming with stacks of paintings, art materials, and props. It looked like a happy place.

Tell me about painting with the three friends you met when you first began painting: George Van Hook, Curtis Otto, and James B. Moore.

I was observing them and soaking it up. I’d ask questions and would often set a painting in front of one of them and ask, “What can I do to make this painting better?”

We had camaraderie and we supported each other because we wanted to see each other get better. I never felt any competitiveness.

George and I painted together daily for almost three years. We’d meet up at first light and paint all over Eureka and Arcata. After meeting George and painting with him each day, my desire to get better and grow became even greater. I was painting 10 to 12 hours every day.

One day George and I were painting at a harbor. He said, “The boats you’re painting have this elongated elegance about them, and you’re squishing them together.” And then he said, “You’re painting with your hand. Put your whole arm into it.” The next day, my boat paintings were 75% better.

There’s no way I would be where I’m at today, had I not met all of them in 1979. At the time, I was embarrassed by my very crude drawings. My landscape painting was very rough.

The year or so I spent doing more abstract work before I moved to Eureka made me fearless as a painter. I’ve never felt timid about putting paint down. My approach, even when I really didn’t know what the heck I was doing, was relatively aggressive.

How did you learn from them without mimicking their styles?

Well, I’m actually quite influenced by George Van Hook. There was a period when a friend coined the term “McHooks” to describe our paintings. Some people said they couldn’t tell the difference between George’s work and my work. But at that time my work tended to have more color in it than George’s did. George’s drawing was more solid as well.

I learned from George by observing his approach to painting, seeing the big shapes and how he blocked in a painting. I also learned by seeing how Jim Moore approached that aspect of painting. Both of them drew beautifully. I wanted and worked toward having more of that in my work. I admired Otto for his design and boldness. [Jim says he learned about figure drawing from Curtis Otto and James Moore influenced his still life set ups.]

When I moved to Wyoming, that’s when I came into my own.

When I was preparing for our interview, I had a brief chat with George Van Hook. He said, “At one point in time, Jim went from being a painter to a master.” Describe your progression.

Wow, it’s quite wonderful for him to say that.

George introduced me to Sargent’s paintings, probably around 1979. I wasn’t familiar with Sargent and various other American painters and European painters because my focus had been the French Impressionist painters and 19th-century landscape painting.

At the time, I said to George, “I will never have that kind of clarity or believability in my work. I feel like my work will always have a cruder quality about it.” I don’t know if those were my exact words, but lo and behold, the more I painted, the more I learned.

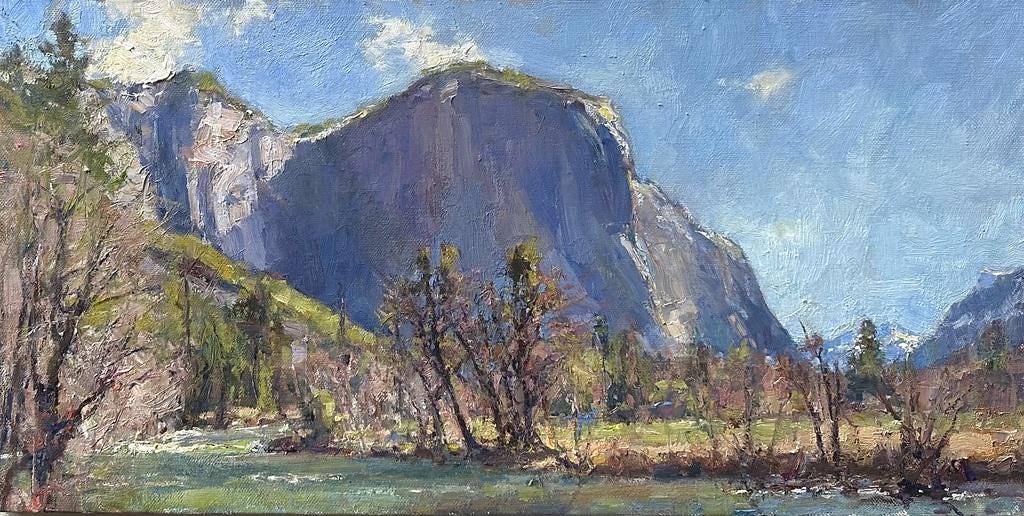

After about five years of painting in Humboldt—three of those with George almost daily, and often with James B. Moore and James Otto, I spent a year painting in Wyoming in 1983. Because of the harsh weather there, I produced more indoor still lifes, but I was incorporating the landscape [by depicting] views through windows. After a year in Wyoming, I returned to Humboldt County with a fresh feeling of how I saw the landscape here. At that point, I felt like I had come into my own a bit more.

What changed about how you painted?

My painting became more believable in terms of the scenes I was painting. I started to understand values [range of light to dark] better, and my drawing got a lot better.

I began trying to paint the atmosphere and air, outside and in, [with less focus on] painting the object. I was thinking about how the air affects the objects and everything else in the still life or landscape, plus those relationships that hold a work together. That realization helped my work evolve starting back in the mid 1990s.

I started using a medium a bit and painting with a good amount of paint, but building it up in layers. I might paint and repaint a wall in a painting six or seven times, which I had never done before.

It was all just very, very direct. Most of my painting up to that point had been not necessarily alla prima [completing a painting in one sitting], but maybe just a couple of sittings. I started spending a month or longer working on a big still life.

You were also viewing art by masters and contemporary artists.

My wife and I visited so many museums all over the East Coast, such as The Met and The Frick. When we came home, I felt like something a little bit different started to happen in my work, that it was evolving.

I was taking in influences of artists other than those who originally influenced me. I was working all the time. Plus, I started using my brain a little bit more, thinking: How do I want to organize my paintings? What do I want to say with this still life? What’s my identity as a still life painter? I wanted to achieve something more.

Besides Vermeer, Monet, French Impressionists, Velázquez, and Rembrandt, so many others have had an impact on my work. I learned from many 20th century artists and so many contemporary artists that I know personally, as well as those whose work I follow on social media.

Because I was a landscape painter, atmosphere and spatial quality [physical attributes, intended use, and emotional impact of a space] interested me. In the early 1980s, I studied Vermeer’s paintings, specifically how he dealt with spatial quality and design. His realism had a nice painterly quality about it; he wasn’t trying to wow us with the objects.

[I studied] the feeling of space in a room and the narrative that Vermeer created with it. As I was painting larger interiors, I was finally connecting all of these ideas. At the same time, my work got to another level. But I still feel that I’m trying to figure things out as a painter.

What are you still trying to figure out?

What I meant by that is that we never really arrive. I’m striving to keep pushing myself and not become comfortable to the point that I’m just repeating what I know works.

I’m really quite insecure and don’t always feel I know what I’m doing. I can get very upset with myself when the work is not going well or feeling right. I often get aggressive with it at that point, which can get me to a better place in the painting and make a breakthrough.

It goes back to my thoughts about jazz music and improvisation: Understand the fundamentals, but then let go so that the work in the moment can take you on a wonderful, unplanned journey.

As musicians respond to what the other players are doing, I’m responding to the subject and the relationship of how it connects and harmonizes to the whole. It’s about being open to changes and not being confined to just the melody or in painting not just following a plan from point A to B that you know ahead of time.

Tell me about working with your gallery that was showing your large interiors.

Hackett-Freedman showed me how wonderful it is when a gallery really believes in your work. I don’t think a lot of us get that. [Hackett-Freedman was a high-end contemporary realism gallery in San Francisco. They convinced Jim to show exclusively at the gallery for many years and he had numerous sold-out shows over a decade. Oftentimes, Jim would send the gallery photos of a painting in progress and it would be sold before he even completed it.]

The gallery also increased the prices of my work. That made me very conscious of wanting to do the best work I could. I still am that way, but I’m at a point in my career where I don’t want to go by rote; I want a little more haphazardness in my painting. I want to sort of feel like I’m sometimes on the edge of a cliff and I might fall, but I catch my balance and I’m able to make the painting work.

How does that translate to how you are painting now?

I’ve returned to using a lot more paint and I’m interested in texture again.

I might block in a painting with my mineral spirits and a little bit of medium, but after that, I’m working with just straight paint. It takes me back to when I first started painting. I want to get back to that kind of energy and the surface quality that I had in my work at that time.

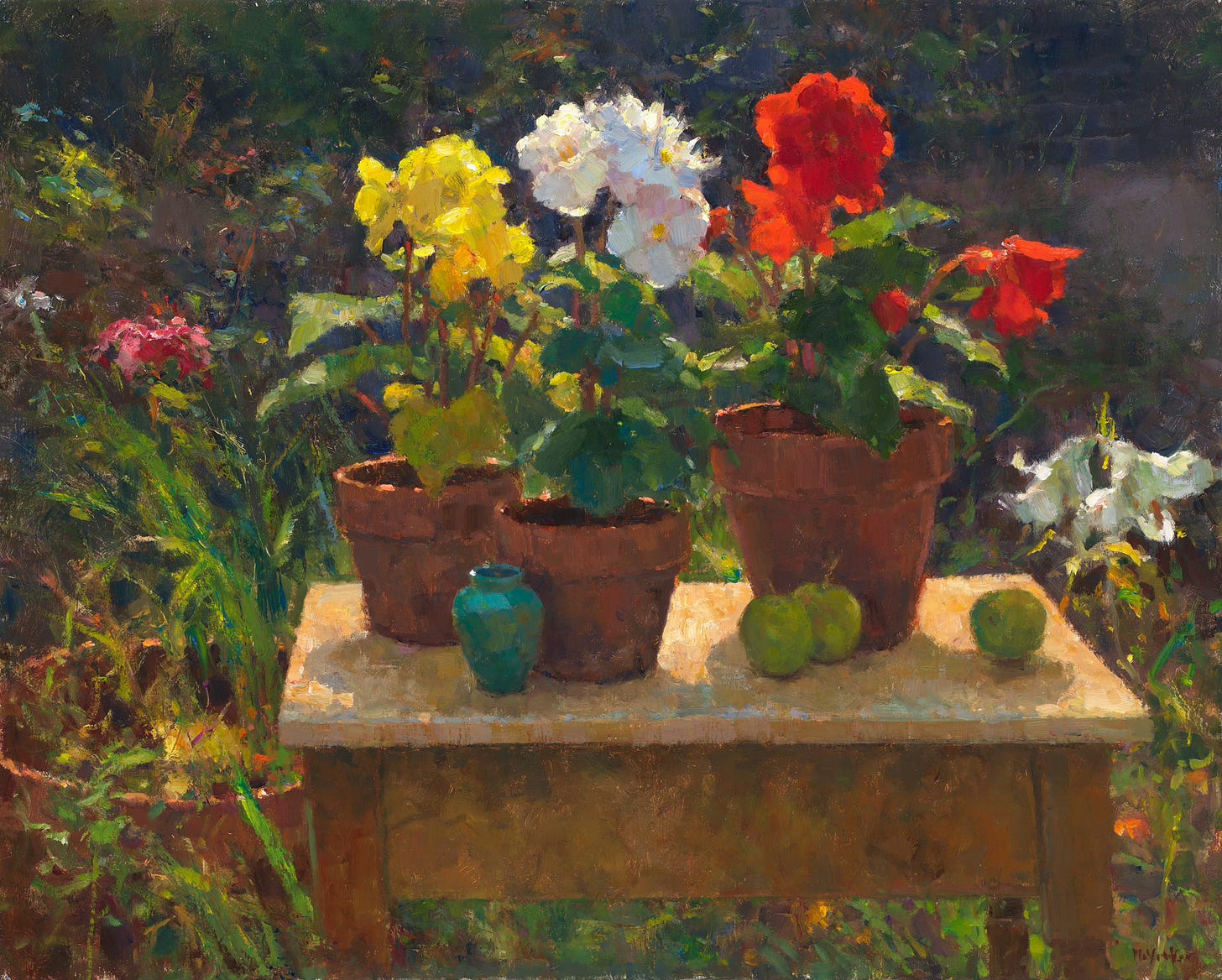

I have a piece that was accepted into the Oil Painters of America show—Studio Lilies, a 30” x 30” still life—that’s one of my favorite still lifes I’ve painted in a while. It shows where I’m at in my head of really wanting to see that paint manipulation as opposed to an illusion of a softer quality.

Your still life paintings have so much “life” in them.

When I made still lifes in the 1990s and early 2000s, I would draw everything in with a paintbrush, not with a pencil. When it began to feel like I was filling in the drawing, I changed my approach. I’d choose an object and start painting its shape and the values and then paint everything around it to relate to that main object. When the shapes feel wrong or off, I will use a line to help me get the shape where it should be.

A friend of mine called this approach painting from the inside out, rather than having lines that felt confining.

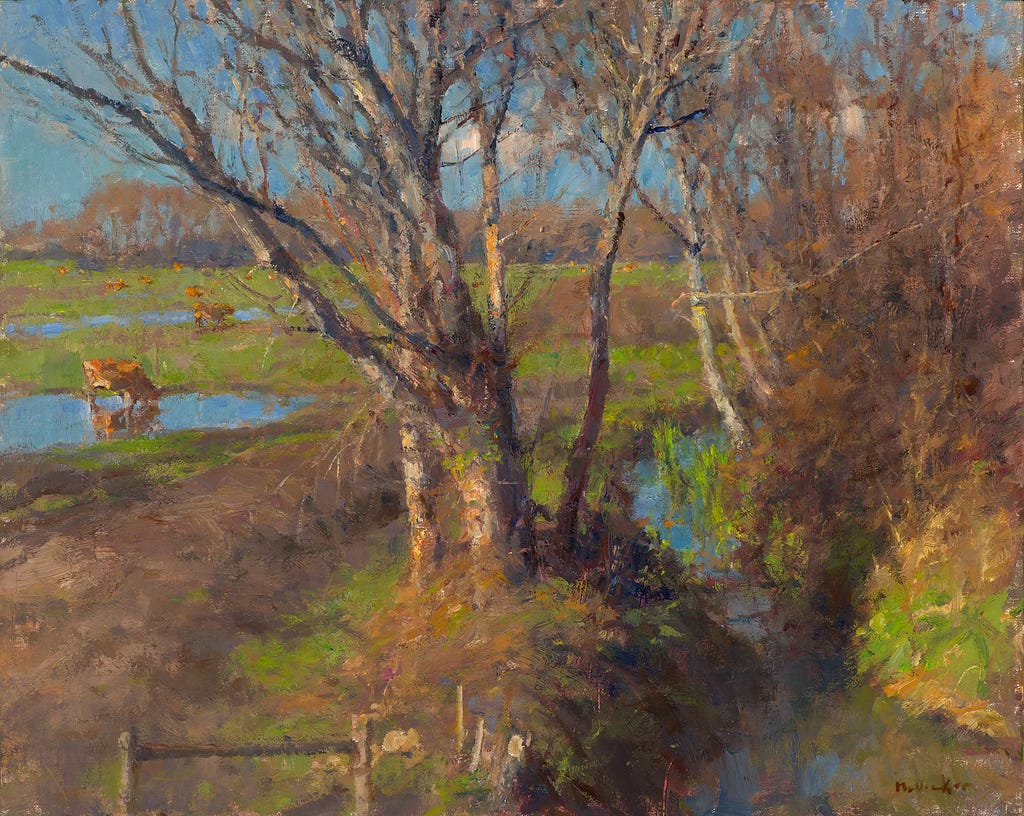

Your environment plays such a significant role in your painting. For people who don’t know Humboldt and the surrounding area, can you describe it?

Much of it is rural. Loleta, where I live, is a dairy community. There are cows across the street and horses up the road.

The coast here is phenomenal. We’re about five miles from the ocean. From my studio back deck, I can see the ocean off in the distance. The diversity of the landscape is one of the things that I love about this place. I grew up in the Los Angeles area. I moved up here because I wanted to be somewhere totally different than the busyness of LA. Within a half hour, you can be up in the hills or at rivers. Within 40 minutes, you can be up into the mountains.

I also like painting the towns. There are great street scene possibilities, not only in Loleta, but up in Eureka, where there are bigger structures.

You painted a series documenting the demolition of the Loleta Creamery Building in your town. What drew you to that subject matter?

Loleta is a little town with maybe 700 people. The creamery had been a thriving business since the late 1800s, but it hasn’t functioned as a creamery for probably 25 years. [The building was vacant for a while and was condemned after suffering significant earthquake damage about four years ago.]

It was a beautiful old brick building in the downtown. I loved the shapes and the way it sat in town. I’ve included the building in at least 20 different paintings since we’ve lived here. [He’s preparing for a show at the Morris Graves Museum in downtown Eureka in 2026 and will include a collection of paintings depicting the building at different times before its ultimate demise.]

One day when I went to pick up my mail, I saw that demolition had begun. I started going down there daily when the weather was good because I wanted to paint it in the sunlight. I set up across the street and wore a mask at times because debris was blowing in the air. [Jim cites George Bellows’ New York City construction paintings as an influence.]

I produced eight paintings on location. The largest one is 24” x 48,” and the others range from 12” x 16” to 18” x 24.” I painted the smallest one at the beginning of the demolition, before they moved the debris out. I’m really happy with the little painting, which was a totally spontaneous piece.

I want to create a large version using my study and the many photos I took to help with certain aspects of it. For years, I never used photos or took a photo thinking I might make a painting of it. It took me a long time before I felt like I could use a photo I took but still approach the subject as if I was outside painting the scene.

How do you use a photo that way?

Now I can look at a photo and see the overall picture and know where I would go with it, whereas before I was relying on the photo to give me all the information I needed.

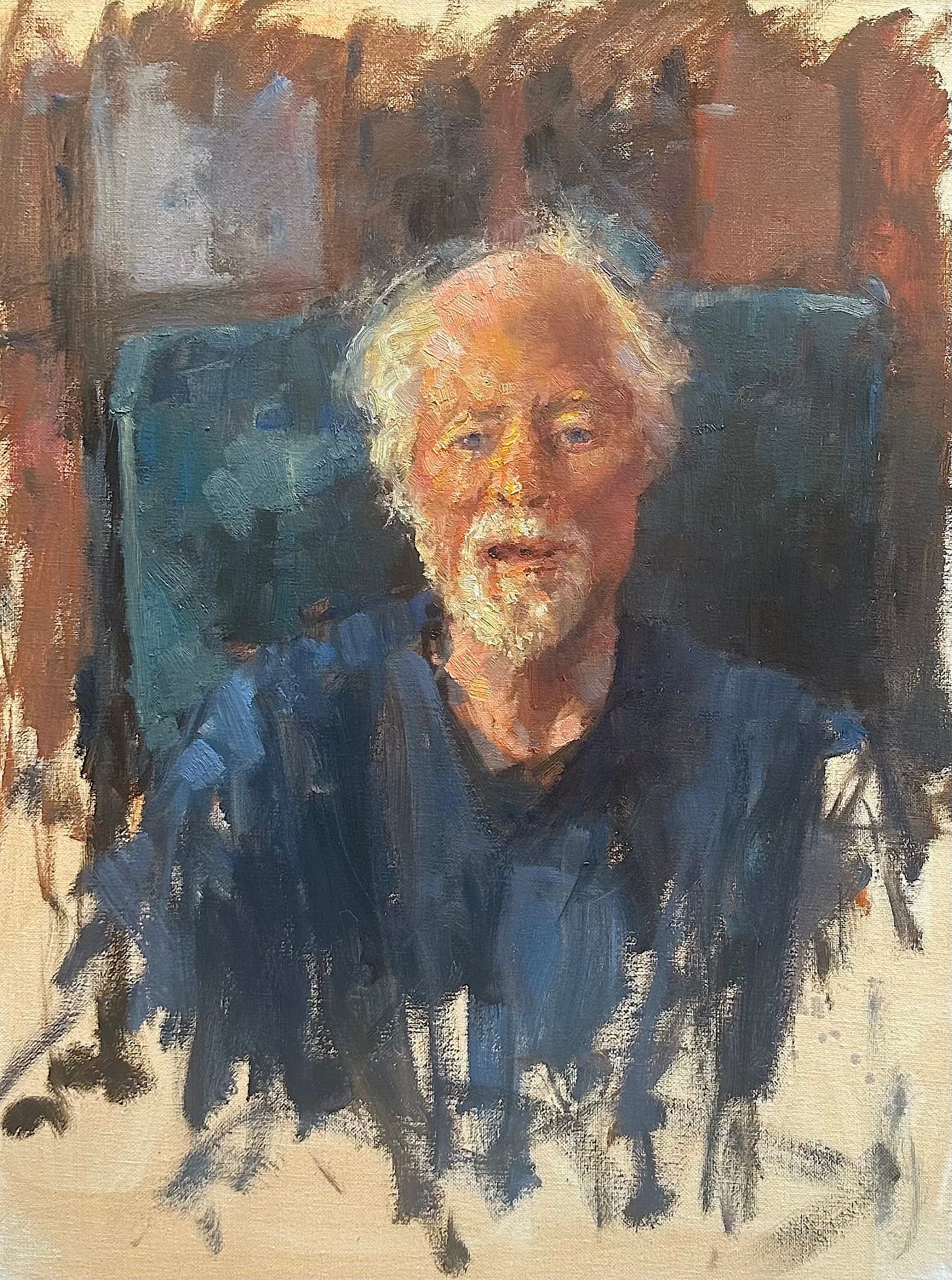

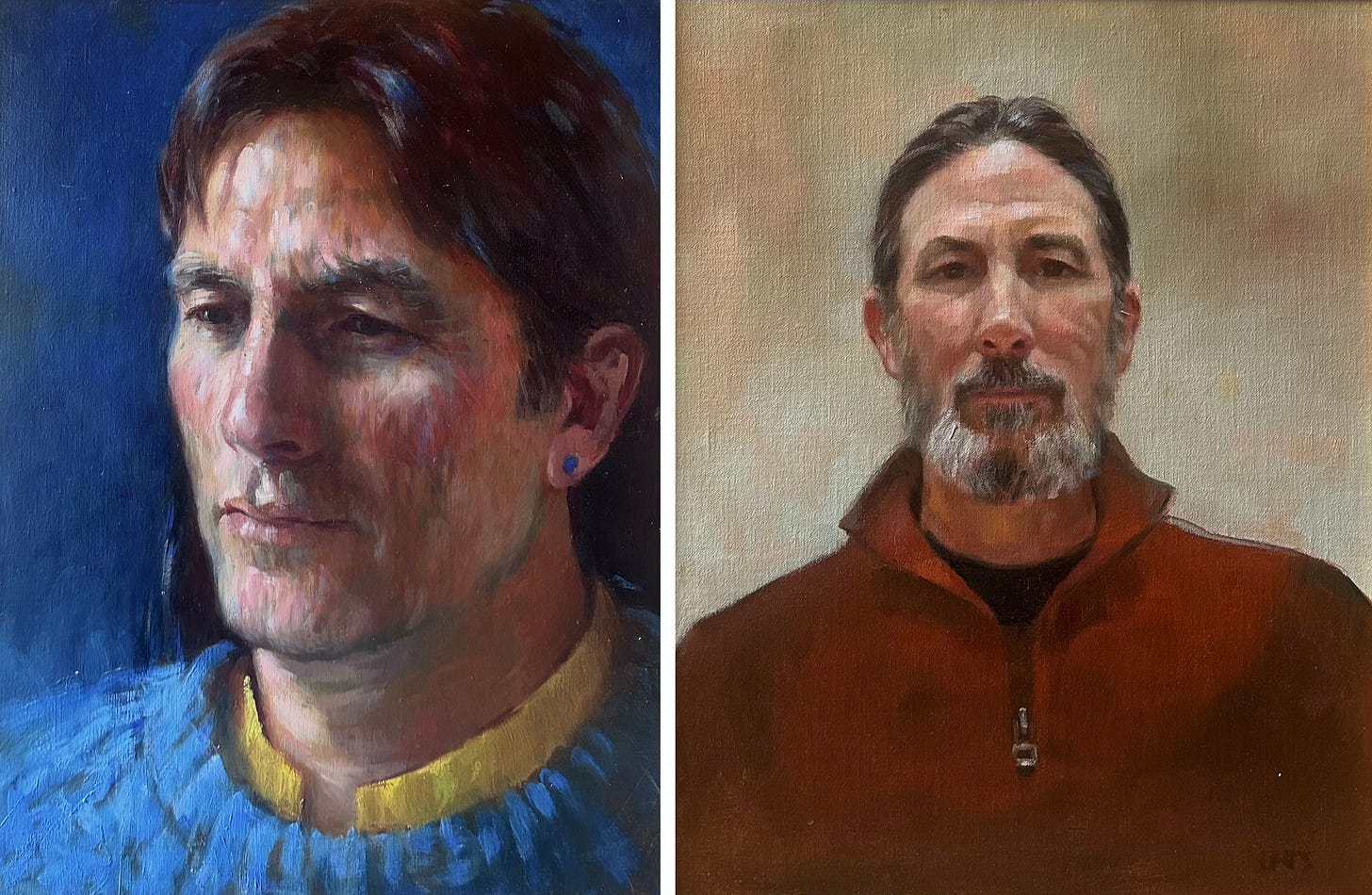

You’ve painted a lot of self-portraits, and you create one every year for your birthday. What are you learning about yourself as you’re painting your portrait?

Usually, I’m cursing myself and telling myself, “You don’t even know how to paint. You’re making a mess!”

Self-portraits are a way for me to take an inner look and see what sort of mood I’m creating. Things going on in our lives affect us and affect our work. I see my weaknesses in my work, but I see the strengths and wonder, how can I make those two work better together?

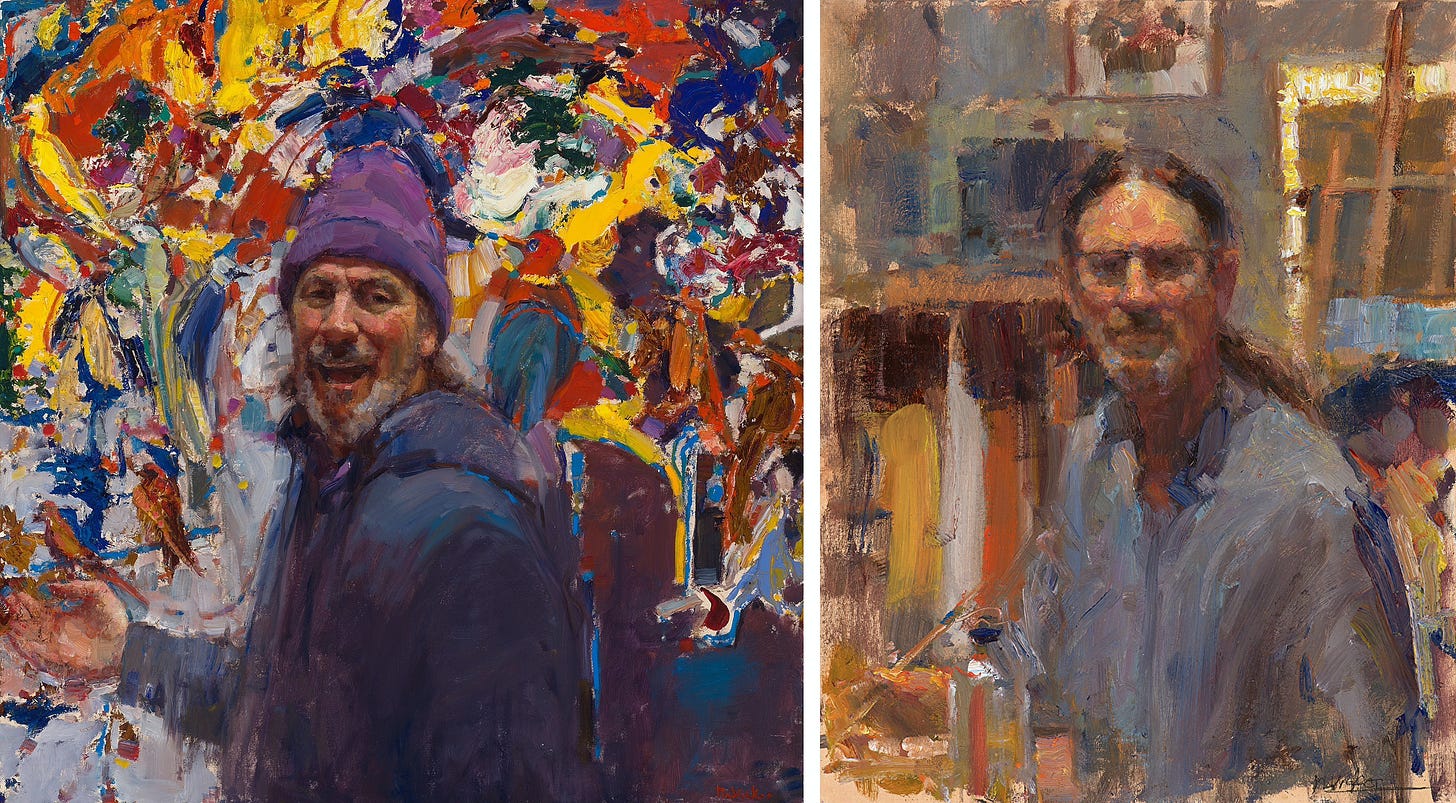

I love painting the figure and would like to get back to doing more of it, but I’m not interested in hiring models. This past year, I painted many artist friends, either out in the landscape or in their studios.

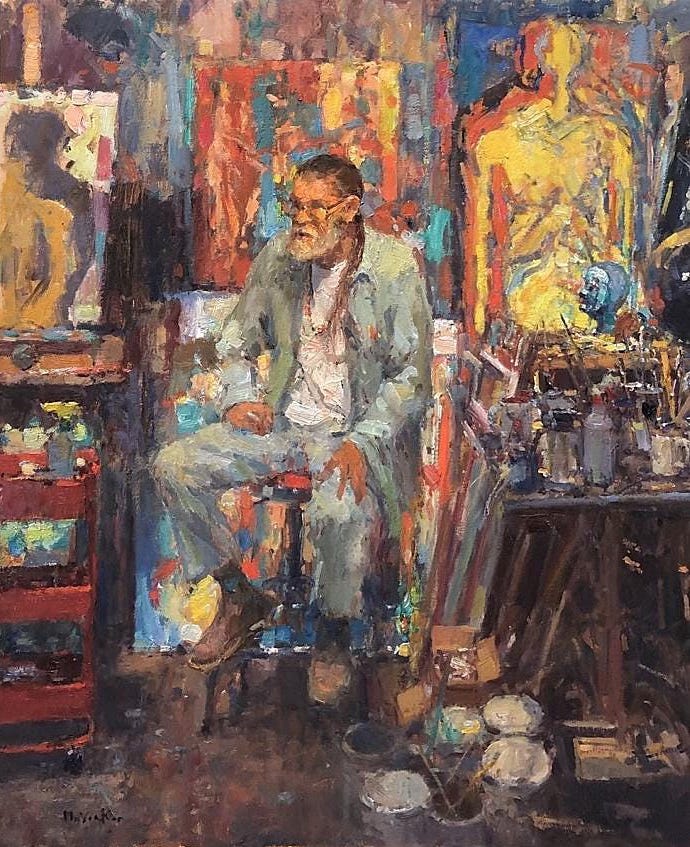

Your portrait of your friend Bill Cody has an exciting energy to it.

Bill’s from New York and he’s got what us Californians think of as a “New York personality”—he’s a very funny and smart guy.

While visiting with him, I made an oil painting of him and several drawings. Painting other artists is the most enjoyable portrait painting I do.

What do you like about painting portraits of artists?

There’s the art connection, and they relate to the process. Their expectations are a little different than people who commission portraits.

I don’t feel uptight about making the painting. If it works out, it works out. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

How has your wife Terry influenced your work?

I met Terry in 1984. She graduated from the Fashion Institute in New York and had a beautiful portfolio of figurative work. Her method of painting and the way she approached the figure was so different than mine. It had a real impact on my work. A friend observed that when I met Terry, my color got more vibrant.

Do you think that Terry influenced you because you were observing her work or because you fell in love and your life changed?

All of that. We talked about art a lot, and we looked at a lot of art together.

We hired models together quite a bit in the early 1990s and into the 2000s. That’s when we both had studios in downtown Eureka. Her work was traditional, but it was also more interpretive. She always maintained her individuality, and I always loved that.

Having a partner that I’m painting around all the time and walking into her studio space to see what she’s been working on that day—I always found that fascinating and thrilling.

We would never say what we thought about each other’s paintings unless the other person asked because it could get a little sticky. She had a clearer sense of figurative work than I did, so I could ask, “What’s bugging me about this figure in my painting?” She would zoom in on it and help me understand how I could make it better. I did the same thing for her.

She also helped me with marketing—not doing the marketing, but helping me to gain confidence in that whole process and find more strength and belief in my worth.

In the documentary, Jim McVicker: A Way of Seeing, you said that you don’t want your paintings to have generic ideas of what things are supposed to look like.

I used to call myself an “observational painter” because I think observation is important to a realist.

It’s different than learning, “this is how you paint trees and this is how you paint cars,” or any number of objects that are in the landscape. It’s about really looking at what you’re painting to figure out, why does that tree excite you? What is it about it that makes it work? It’s easy to get into a little bit more of a generic idea of what a tree is.

I love landscape paintings that have an identity to where they were painted. I look at what the grass is doing and how it moves, how the light wraps around something.

You’re known for making very large plein air paintings and for having a specific method for producing them.

I’ll work on a painting for an hour and a half to two and a half hours at a time with multiple sittings outdoors. Then I’ll take the painting back out at that same time each day. When I’m working on a large landscape, I generally set it aside after about a month because the season changes. I’ll take it back out [the following year at the same time of the season] to finish it.

I’ve been working much smaller lately and finding how much I like that. I’ve always wanted to bring some of the spontaneity that I can get in a small canvas to a bigger one.

What’s the largest canvas you’ve painted outside?

I painted a friend’s ranch that’s up the road, and I think it was 54” x 90.” I painted it at high noon in the summer because the morning fog tended to burn off by then. At that hour, there was this wonderful shadow created by the big cypress trees.

Many landscape painters tend to like painting very early or very late in the day. I like both of those, but I’ve grown to find mid-morning and mid-afternoon light more challenging because it doesn’t have that drama of the morning light. There’s something I like about trying to capture the atmosphere of that time of day, the brightness of it and the rich color.

You shared on Instagram a still life painting you made while listening to John Coltrane. How did his music influence your painting?

I became more spontaneous and more aggressive with my application of paint, the more aggressive his playing became. I love jazz and I listen to it a lot. [Jim plays saxophone.]

The really great players can tap into their substantial knowledge and improvise—whether it’s on the melody or the chord changes, or whatever—and play a solo that they will probably never play twice the same way. I liken that to painting.

I’ve been painting for 50 years. There’s still a lot to know and learn, but I know a lot after all this time. I want to be like those jazz improvisers and just let my brush fly, without feeling that I need to be in control.

I’m using my palette knife a lot more than I used to. As an example, I may be working on a tree and I want more paint on it. I’ll take a whole bunch of palette knife mixings, push it around on the tree and then take my brush and work back into it. I’m approaching it with a spontaneity that’s not completely ignorant of paint, which I would have been 45 years ago.

What do you do when you feel like a painting isn’t coming together?

Oftentimes, I get more aggressive with the paint application. I try to step outside myself and let my intuition completely take over, saying I don’t care if this works, I don’t want to play it safe, and I want to push it further. A lot of good things happen working that way. I like not being overly controlled in my process.

I usually slow myself down near the end of a painting and make more thoughtful decisions. At that point, I allow my brain to tell me what is and isn’t working.

Painting and trying to make art are so much more than a learned process that one always applies to the work. It’s about trying different things and making paintings where you don’t quite know where they’re going. Miles Davis was once asked why he didn’t play ballads anymore. His answer was, “Because I can.”

I often get myself in trouble and then see if I can get out of it.

Do you ever take risks and find that it doesn’t work out?

It often does not work out, but I usually keep going at it until I think it works. Sometimes I will just put it aside, but I’m pretty stubborn, so I either make it work or ruin it. That’s often depressing when that happens, but by moving on, I get over it.

Lightning round

What’s the favorite piece of art that you own?

A desert painting James B. Moore made back in 1989. We acquired it maybe 10 or 12 years ago. He and his wife saw a huge landscape of mine, a 4’ x 5’ studio piece of Yosemite, that was probably the best studio piece I ever did. They wanted to buy it and I suggested a trade because the desert painting had never left my mind.

What’s your most captivating art viewing experience?

We went to Chicago just to see a Monet retrospective about 20 years ago. It included pieces he made at 17 and through to his late paintings. I had seen the lily pond paintings in books, but when I saw them in person on the wall, I thought “Oh, my God.” I’ll never forget being in the last room with the massive water lilies paintings. A woman was listening to the audio guide, and tears were running down her cheeks.

[Jim shared many other favorite art viewing experiences: a Sargent retrospective at the Whitney Museum in the mid-1990s; a Frederic Church show; and a Twachtman exhibit of snow paintings at the National Gallery.]

What’s been your most memorable meal?

I celebrated my 21st birthday in Barcelona with my girlfriend at the time. We hitchhiked for two months all around Europe. We found this little restaurant down an alley where they served paella in this large pot filled with rice and seafood, all for five bucks.

Palate & Palette menu

Here’s what I would serve if Jim and Terry came for dinner, which they are invited to do:

Salad of green leaf lettuce, radishes, asparagus, and a zesty apple cider vinaigrette

Paella

Chocolate cake

Where to find Jim McVicker

Jim McVicker Fine Art

@mcvickerpaints

Brushworks Gallery, 160 800 S., Salt Lake City

George Stern Fine Arts, 73320 El Paseo, Palm Desert, CA

Illume Gallery West, 130 E Broadway St., Philipsburg, MO

Susan Powell Fine Art, 679 Boston Post Rd., Madison, CT

Waterhouse Gallery, 1114 State St #9, Santa Barbara, CA

Winfield Gallery, Dolores St., Carmel, CA

American Legacy Fine Arts, 949 Linda Vista Ave., Pasadena, CA

Huse-Skelly Fine Art Gallery, 229 Marine Ave., Ste. E, Balboa Island, CA

J.M. Stringer Gallery, 3465 Ocean Dr., Vero Beach, FL

If you liked this story, you will want to check out Palate & Palette interviews with:

George Van Hook

Dale Ratcliff

Stapleton Kearns

T.M. Nicholas

C.W. Mundy

Cynthia Rosen

John Terelak

Leo Mancini-Hresko

Also…

-

Show your appreciation by clicking the LIKE button below—I’d love to know you enjoyed the story, AND more likes help more people discover Palate & Palette.

-

Forward this to a friend and encourage them to subscribe.

-

See more than 60 stories about art and food at palateandpalette.substack.com.