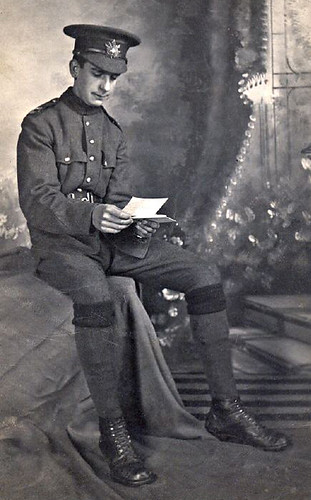

Private John Alexander Barber / June 25, 1897 – Sep 30, 1918

Image by bill barber

From my set entitled “Barbers in the Military”

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/sets/72157600289206206/

In my collection entitled “The Barbers”

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/collections/

In my photostream

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/

My Uncle John Barber enlisted in 1916, and gave his date of birth as June 25, 1897. He was with the Canadian Infantry (Central Ontario Regiment), 75th Bn. There is some indication that he lied about his age in order to enlist. My understanding is that he was killed when a stove exploded in a Belgian army camp.

In a few weeks, I will be travelling to Archives Canada in Ottawa to check his war records along with those of my Uncle Art Barber who also served in World War I. Art died about twenty-five years ago. I also hope to check my father’s records. He was much younger than Art and John, and served in World War II. Dad died in 1954, and would have been one hundred years old this year (2008)

In his attestation papers, John identified his trade as butcher.

He is one of the people I will be remembering tomorrow

Burial Information:

Cemetery:

CANTIMPRE CANADIAN CEMETERY

Nord, France

Location:The route to the Cantimpre Canadian Cemetery is signposted from the D939 at Raillencourt and is located 1 kilometre north of Sailly on the D140 on the left hand side of the road towards Sancourt. Sailly is a village in the Department of the Nord approximately 3 kilometres north-west of Cambrai just to the north of the main road from Arras to Cambrai (D939).

The "Marcoing Line," one of the German defence systems before Cambrai, ran from Marcoing Northward through Sailly to the West of Cantimpre and the East of the village of Haynecourt. The Cemetery at Cantimpre was originally called the Marcoing Line British Cemetery.

Reproduced from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Expeditionary_ForceThe

The Canadian Expeditionary Force was the group of Canadian military units formed for service overseas in the First World War. As the units arrived in France they were formed into the divisions of the Canadian Corps within the British Army. Four divisions ultimately served on the front line.

The force consisted of 260 numbered infantry battalions, 2 named infantry battalions (The Royal Canadian Regiment and Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry), 13 mounted rifle regiments, 13 railway troop battalions, 5 pioneer battalions, as well as field and heavy artillery batteries, ambulance, medical, dental, forestry, labour, tunnelling, cyclist, and service units.

A distinct entity within the Canadian Expeditionary Force was the Canadian Machine Gun Corps. It consisted of several motor machine gun battalions, the Eatons, Yukon, and Borden Motor Machine Gun Batteries, and nineteen machine gun companies. During the summer of 1918, these units were consolidated into four machine gun battalions, one being attached to each of the four divisions in the Canadian Corps.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force was comprised mostly of men who had volunteered, as conscription was not enforced until the end of the war when call-ups began in January 1918 (see Conscription Crisis of 1917). Ultimately, only 24,132 conscripts arrived in France before the end of the war.

Canada was the senior Dominion in the British Empire and automatically at war with Germany upon the British declaration. According to Canadian historian Dr. Serge Durflinger at the Canadian War Museum, popular support for the war was found mainly in English Canada. Of the First Division formed at Valcartier, Quebec, ‘fully two-thirds were men born in the United Kingdom’. By the end of the war in 1918, at least ‘fifty per cent of the CEF consisted of British-born men’. Recruiting was difficult among the French-Canadian population, although one battalion, the 22nd, who came to be known as the ‘Van Doos’, was French-speaking.

To a lesser extent, other cultural groups were represented with Ukrainians, Russians, Scandinavians, Italians, Belgians, Dutch, French, Americans, Swiss, Chinese, and Japanese men who enlisted. Despite systemic racism directed towards non-whites, a significant contribution was made by individuals of certain ethnic groups, notably the First Nations[1], Afro-Canadians and Japanese-Canadians.

The Canadian Corps with its four infantry divisions comprised the main fighting force of the CEF. The Canadian Cavalry Brigade also served in France. Support units of the CEF included the Canadian Railway Troops, which served on the Western Front and provided a bridging unit for the Middle East; the Canadian Forestry Corps, which felled timber in Britain and France, and special units which operated around the Caspian Sea, in northern Russia and eastern Siberia.[2]

After distinguishing themselves in battle from the Second Battle of Ypres, through the Somme and particularly in the Battle of Arras at Vimy Ridge in April 1917, the Canadian Corps came to be regarded as an exceptional force by both Allied and German military commanders. Since they were mostly unmolested by the German army’s offensive manoeuvres in the spring of 1918, the Canadians were ordered to spearhead the last campaigns of the War from the Battle of Amiens on August 8, 1918, which ended in a tacit victory for the Allies when the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force lost 60,661 dead during the war, representing 9.28% of the 619,636 who enlisted.

The CEF disbanded after the war and was replaced by the Canadian Militia.

Post Processing: slight healing brush, crop