Roman Chester – Deva Victrix – is one of the unquestioned ‘great sites’ of Roman Britain. This was a major military centre from its late 1st-century AD origins through to its abandonment in the late 4th/early 5th centuries AD, and significant parts of the town survive beneath the medieval and modern city. Current Archaeology has been on site there since the start of the magazine, and its repeated visits shine a light not just on the evolution of the town, but also on its wider regional and national context.

INITIAL INSCRIPTIONS

The magazine paid its first visit to Chester in CA 2 (May 1967) to examine two new inscriptions discovered during works clearing the amphitheatre prior to opening it to the public. One was a devotion to the goddess Nemesis, comparable to those known from the shrines around the amphitheatre at Carnuntum (modern-day Petronell) in Austria; the other was a graffito reserving a seat for a man named Seranus. Modern-day attendees at nearby Chester racecourse might recognise the impulse of the latter, and this mix of the divine and the day-to-day could be said to sum up Chester down the ages: it is a place with a reputation as a serious party town. But after this early appearance, it took until CA 84 (October 1982) for Current Archaeology’s first in-depth report, which examined life in the 4th century, at the end of the Roman era. Excavations were telling the story of the abandonment of parts of the fortress and the transformation of others into a purely administrative rather than military centre. This fieldwork also revealed the complicated earlier history of the site – of its foundation in the late 1st century AD, and then its partial abandonment in the early 2nd century when a large part of the legion moved north. There it spent half a century building first Hadrian’s Wall and later the Antonine Wall. Only towards the end of the 2nd century did Chester arise again as the XX Legion’s headquarters.

DOING THE ROUNDS

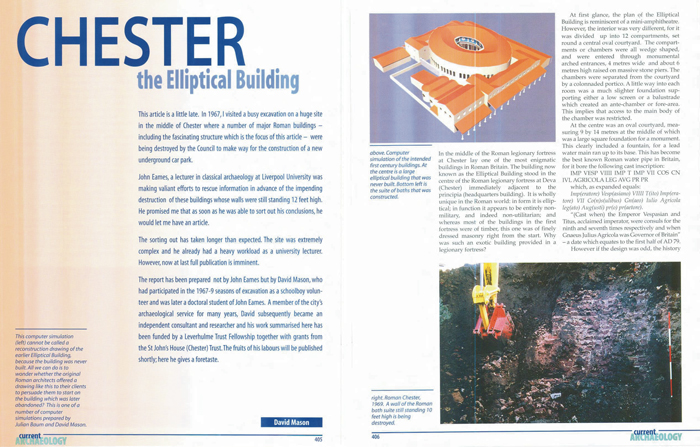

It was not until CA 167 (March 2000) that the magazine returned to Chester, and in unusual fashion. As that article explains, the town’s two famous elliptical buildings were originally identified in 1939 near the market hall, before the commencement of the Second World War put a stop to fieldwork. The local council picked up excavation of the buildings again in 1967, in advance of a new car park. However, like so much archaeology of that era, this data then sat unexamined and unpublished for decades before finally seeing the light of day. The results were worth the wait: the buildings, located near the centre of the Roman fortress, were found to date to the late 1st century, not long after Deva’s foundation. The first structure measured 52m by 32m and had an oval courtyard with a water feature at its centre, surrounded by 12 wedge-shaped rooms; the second was constructed on top of the first in around AD 220, its design modified using different diameters of arc to achieve a ‘fatter’ design. The quality of construction of these buildings and their unusual design led to the hypothesis that they were built by order of provincial governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola, with Deva as his administrative headquarters – in effect the early capital of Britannia, before Londinium rose to prominence.

LET THE GAMES BEGIN!

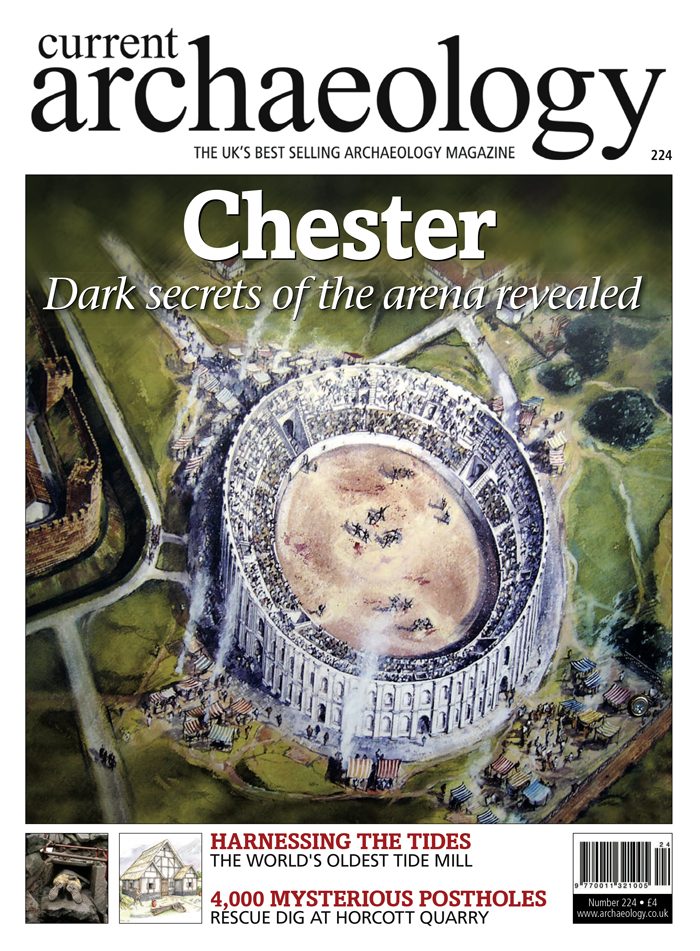

CA 193 (August 2004) saw the magazine back in more familiar territory, when renewed fieldwork took place at the amphitheatre. English Heritage and the local council (the same that had demolished most of the elliptical building during their works in the 1960s) had initiated this work to improve access and interpretation of the site given its importance, not least for the tourist economy. Subsequent visits in CA 224 (November 2008) – Deva’s only cover story – and CA 304 (July 2015) shed further light on our understanding of the amphitheatre. As CA 224 explained, previous fieldwork there had often been crude, quickly machining down through later layers to get to the Roman era, though it had set an established chronology for its construction. The fieldwork of 2004-2006 was more forensic, re-examining those parts previously explored as well as others previously left unexcavated. This work revealed that there was a first, stone-built amphitheatre constructed around AD 80-90. Within a decade of this, major modifications then raised the seating and deepened the arena. Later (probably in the late 2nd century AD), the amphitheatre was extended and enlarged. Crucially, these works included the construction of an outer wall 1.8m beyond the earlier boundary, and this sealed a sequence of deposits that had built up outside the original outer wall, offering an insight into what had gone on immediately outside an amphitheatre. Roman wall paintings from elsewhere in the empire, especially Pompeii, depict temporary booths and stalls in these spaces, akin to those at a modern-day showground: this was also the case at Chester, alongside the remains of a small shrine.

This fieldwork gave insights, too, into the amphitheatre’s later use, from the 3rd century right into the ‘Dark Ages’. CA 304 (July 2015) returned to the results of these 2004-2006 excavations from the opposite chronological end, examining the pre-Roman uses of the site, which revealed a rich history dating back to the Mesolithic, including excellent Middle Iron Age deposits such as a small house. This is the most recent in-depth visit of the magazine to Chester, but for those of you interested in the wider history of amphitheatres and their use during the Roman era, I flag CA 397 and CA 402 (April and September 2023) as well. Both of these examine the evidence of the lives – and deaths – of the gladiators who plied their distinctive trade in such places. And Current Archaeology’s founder and editor in-chief Andrew Selkirk dived into this murky world, too, in CA 209 (May 2007), reporting from a two-day conference held in Chester in February 2007 discussing what it really was like to be present at an amphitheatre, either as a spectator of or a participant (willing or unwilling) in the contests that unfolded within.

Before I conclude this column, I will mention three further issues that touch on the wider evidence for the Roman occupation of Britain, which those of you keen on this subject may find useful. First, CA 249 (December 2010) is something of a Roman Britain special, including a report on the Crosby Garrett parade helmet discovered in 2010 near the Cumbrian village of the same name (see also CA 287, February 2014, for a deep dive into this fascinating find); a report on Roman armour discovered at Caerleon in South Wales; and an overview of Miles Russell and Stuart Laycock’s excellent book Unroman Britain about the myths that have arisen of this era. Second, CA 251 (February 2011) includes an excellent article

about Stephen Cosh and David Neal’s multi-volume work on Roman mosaics, offering an insight into what changes to the design and location of mosaics tell us about changes in wider society, especially at the tail-end of the era. Third, and most recently of all, CA 409 (April 2024) explores the context and impact of the Roman army in Britain, linked to the British Museum exhibition on this topic that ran between February and June 2024. All of this is food for thought in the context of Chester, a town founded on the Roman military conquest of Britannia, but which evolved into a far more complex urban environment that long outlasted the formal occupation.

The Grosvenor Museum in Chester (www.museumsofcheshire.org.uk/venues/the-grosvenor-museum) includes many finds from the Roman town, and Chester’s Roman Amphitheatre is in the care of English Heritage: www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/chester-roman-amphitheatre. The city also hosts the immersive Deva Roman Experience (https://devaromancentre.co.uk), and there is much to learn from the Chester Archaeological Society (www.chesterarchaeolsoc.org.uk), which is one of the oldest such county organisations in the UK, having been investigating the city since the mid-19th century.

The post Excavating the CA archives – Roman Chester appeared first on Current Archaeology.