Vitruvius & His Orders, Referring to Columns

The “Ideal Architect” has not been a static concept over time but is a reflection of evolving societal values, technological advancements, and artistic movements. Over centuries, this ideal has evolved, from the polymath engineer-philosopher championed by Vitruvius in ancient Rome, through the refined connoisseur-adaptor epitomized by Richard Morris Hunt in the Gilded Age, to the inventive, heroic designer, personified by Frank Lloyd Wright in the 20th century. Examining these distinct archetypes reveals a fascinating trajectory of a profession continually reinventing itself.

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (known simply today as Vitruvius), was an architect who practiced and wrote in the 1st century BCE. In his writings, he laid down one of the earliest and most enduring foundations for the Ideal Architect. His treatise, De Architectura, portrays the architect as a master of both theory and practice, a true “Engineer-Philosopher.” For Vitruvius, an architect needed a vast breadth of knowledge, encompassing geometry, history, philosophy, music, medicine, law, and astronomy. This individual was not merely a designer of buildings but a civic intellectual, capable of understanding and shaping the built environment in harmony with both natural principles and human needs. Vitruvian ideals emphasized Firmitas, Utilitas, and Venustas (Durability, Utility, and Beauty) as the cornerstones of good architecture, demanding a holistic and deeply intellectual approach to design and construction. The architect was a learned generalist, a figure of significant societal responsibility and broad expertise.

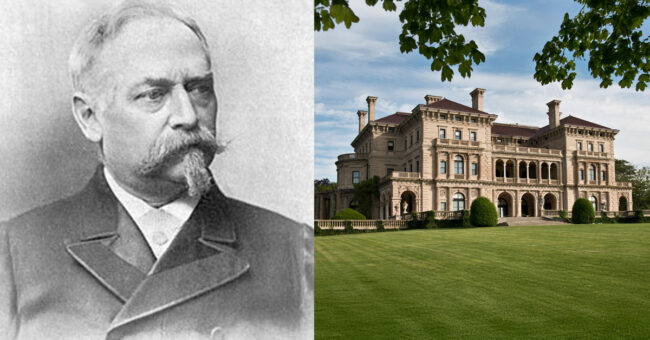

Richard Morris Hunt / The Breakers ( 1893, Newport, RI)

By the late 19th century, the Ideal Architect had evolved, particularly in the burgeoning landscape of America, into a knowledgeable connoisseur, who could adapt old architectural models to more modern-day programs. Richard Morris Hunt, a pivotal figure in American architecture, embodied this “connoisseur-adaptor” archetype. As the first American to attend the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Hunt brought a European sensibility and a refined taste to his commissions. This era, marked by immense industrial wealth and a desire for cultural legitimacy, saw the architect as an arbiter of taste and a skilled adaptor of historical styles. Hunt’s grand residences for the Vanderbilt family, such as The Breakers and Marble House mansions in Newport, or his design for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, showcased a mastery of historical precedent and an ability to translate European grandeur for an American context. The idea here was less about radical invention and more about sophisticated interpretation, cultural curation, and the creation of an architectural language that signified status and refinement. The architect was a learned importer and skilled synthesizer of established forms, guiding the aesthetic development of a rapidly changing nation.

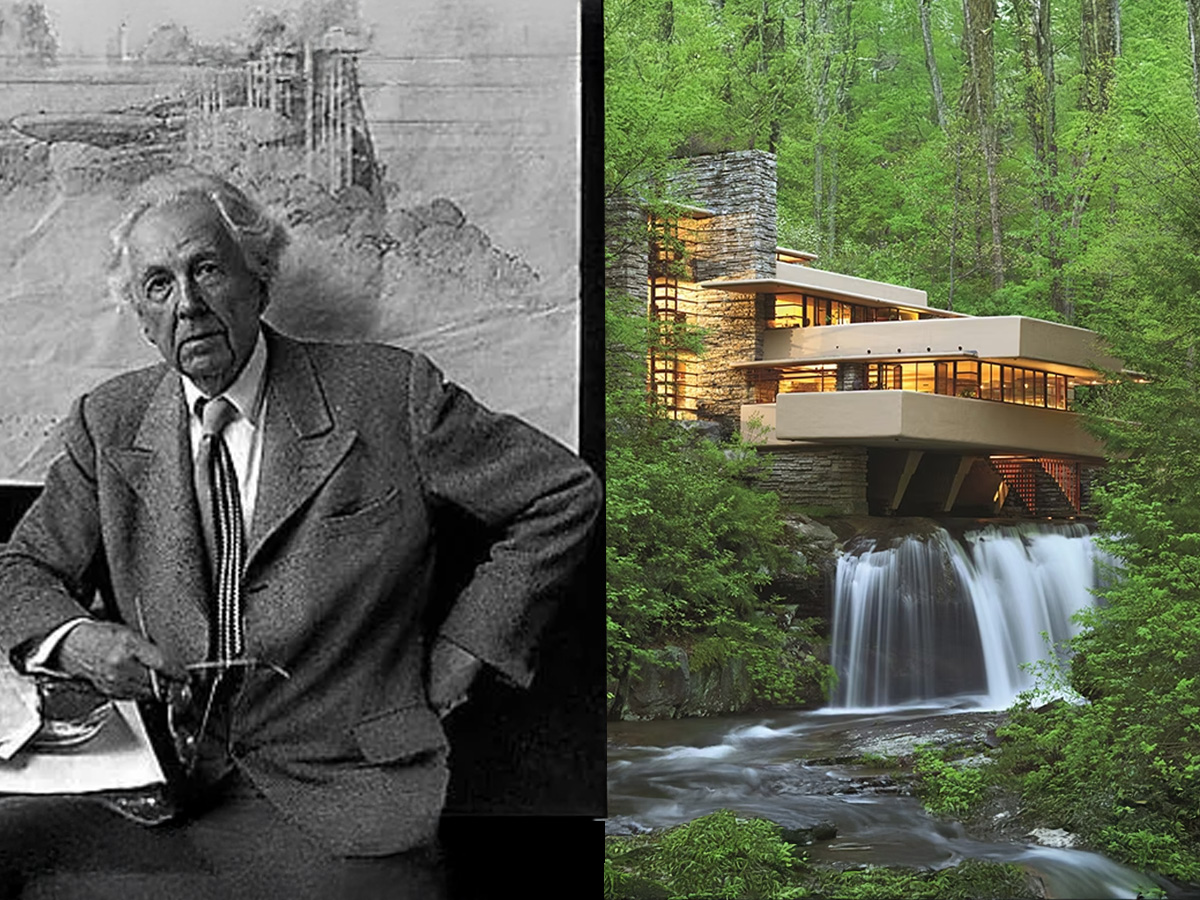

Frank Lloyd Wright / The Fallingwater ( 1936, Millrun, PA)

Less than forty years later, at the beginning of the 20th century, another dramatic shift occurred with the rise of figures like Frank Lloyd Wright, who championed the Architect as an inventive, heroic designer. Wright, with his emphasis on “organic architecture” and a distinctly American design typology, broke radically from European historical eclecticism. He positioned the Architect as a visionary, an individualistic hero capable of forging new forms and new ways of living through sheer creative force. Wright’s pronouncements and his highly original works, (from the Prairie Style homes to Fallingwater and the Guggenheim Museum),projected and an image of the Architect as a singular genius, often at odds with convention, who dictated terms and reshaped the environment according to a powerful personal vision. This ideal celebrated innovation, originality, and the architect’s almost messianic role in crafting a better future through bold design.

Ross Sinclair Cann, AIA / Ocean Avenue Project ( 2014, Newport, RI)

Today, the model is for the ideal Architect less clear. Architectural practice has changed more in the last 20 years than in the previous two hundred years, with computer modeling and animation taking a major role. The older architects are still strongly influenced by figures like Hunt and Wright, but the younger architects are still seeking out new role models for the “Ideal Architect” to better suit the world and practice as they find it. Artificial intelligence, although still not powerful enough to manage the multiple complexities of architectural design, is a cloud on the horizon, with its impact on the future of Architecture still highly speculative. Perhaps we will try to combine the best of all the previous models of practice that have come before: the technical breadth of Vitruvius, the erudition and connoisseurship of Hunt, and the raw inventiveness of Wright. If we can do that, then perhaps the “Ideal Architect” will continue to practice this ancient and complex craft capably, far into the future.

Ross Sinclair Cann, AIA, LEED AP, is a historian, educator, author, and practicing architect living and working in Newport for A4 Architecture and is Founding Chairman of the Newport Architectural Forum. He holds honor degrees in Architecture and Architectural History from Yale, Cambridge, and Columbia Universities, teaches in the Circle of Scholars program at Salve Regina, and has been a licensed architect since 1992.