In recent years, I haven’t played much chess, mainly due to health problems that significantly limited my freedom. Thanks to a kidney transplant, I regained my freedom and started refreshing my opening repertoire. Let me get straight to the point: it’s anything but simple. Why?

What’s the Biggest Bottleneck?

Opening books. My relationship with them is a kind of love-hate affair—with a lot more hate than love. That’s why I didn’t quite understand the following incident.

Once, I received a call from a thrift shop. They had received a large batch of chess books and asked if I was interested. Since I have two great hobbies—chess and collecting chess books—I took the bait. The books were available for a bargain price. But what immediately struck me was that the chess player who left these books behind (or was it their family?) apparently had a strong preference for opening books. More than three-quarters of the collection revolved around openings.

In the end, I took a few books; the collector in me couldn’t resist. But honestly, I didn’t get it at all. What does someone do with so many opening books?

I have a few, mostly gathering dust, on my shelfs as well. They all have one thing in common: I’ve never read any of them cover to cover. Most of the time, I’ve stopped reading early on. There are several reasons for this. The authors:

- Present (some of) the variations that don’t interest me.

- Overload their readers with a flood of variations.

- Seem to possess phenomenal memory skills.

- Are way too far above the material and have no idea how to present it properly.

Is That All?

Asking the question that way surely suggests there’s more to it. Let’s take a look at what the average chess player actually expects from an opening book. In my opinion, they want:

- An overview of the key variations, elaborated on the main lines.

- Core strategies, positional patterns, and plans.

- The typical tactical motifs associated with the opening.

- The endgames that frequently arise from this opening.

Such an overview is sorely missing from the vast majority of opening books. Often, they even start with ‘Less common continuations.’ If there’s one thing I don’t want, it’s moves that I’ll likely never encounter in practice.

A decent overview of the key variations can already be found on a website like Lichess (explorer), or Chess.com (explorer) where you can see which continuations are most played per opening. Want to check this at a higher level? Then the Live Book function of the ChessBase (Live book) software provides an excellent overview.

Practice online

IM Willy Hendriks, a well-known author of several excellent books, also offers great advice: play online. You’ll encounter players of roughly the same playing strength. In this way you quickly get an idea what they play. You can take that into account when building your opening repertoire. Preferably play rapid and analyze your games.

Why Do I Want to Know These Things First?

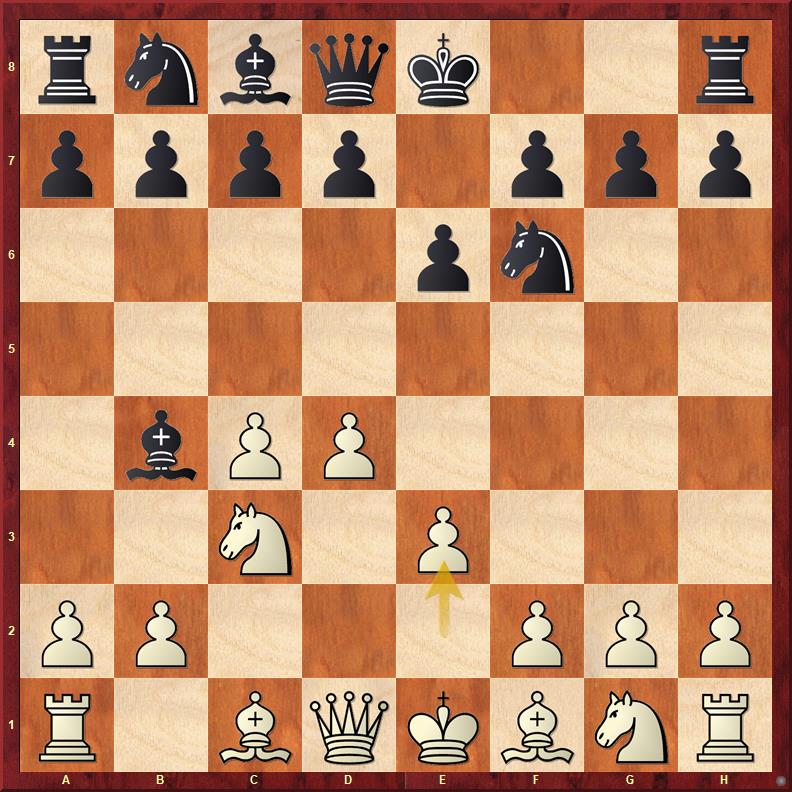

Let’s start with the first point. A good overview gives me a better idea of what to expect. And by an overview, I don’t mean the detailed variation indexes that often appear at the beginning of each chapter with lots of details, but just the main structure of the opening. Take, for example, the Nimzo-Indian:

Think of fourth moves like 4. e3, 4. Qc2, 4. a3, 4. f3, 4. Bd2, and 4. Bg5. This overview is certainly not exhaustive, but it includes the most important continuations. An author could indicate the primary structures they want to cover for each fourth move and explain the plans and positional ideas that go along with them and illustrate them with flashcards.

Once this image is clear, the author can also highlight the most important tactical motifs. For example, in the Najdorf, white has the option to sacrifice a knight on d5 in some variations. Meanwhile, in the Najdorf (and other Sicilian openings), black can often take advantage of the c-file—for instance, through an exchange sacrifice on c3. Of course, there are many more tactical ideas per opening, and an opening book should make these transparent.

And Why Endgames?

Isn’t it an opening book? Why endgames? Well, openings often lead to rather specific endgames. Take, for example, the Karlsbad structure that can arise from the Queen’s Gambit (but also through other openings). This structure frequently leads to certain types of endgames.

The idea behind this is that an opening book should provide the reader with a kind of roadmap. That way, it becomes much easier to learn and remember specific variations. Why? Because signposts are placed in the overview. It offers a framework that the chess player can build upon.

Structure and Framework: Essential in Any Learning Process

I have taught for over twenty years. Granted, in a completely different field than chess. But one thing all lessons have in common:

- Don’t overwhelm people with excessive information—first provide structure and a framework.

- Keep the presentation short and concise without unnecessary details.

In a good opening book, information should be presented in digestible chunks. For instance, on Chessable, I see video introductions lasting over an hour. That is far too long. One author even said:

“You shouldn’t complain that I’m going so fast—I just have a lot of information.”

That doesn’t work. An introduction should be refreshing and clear, not a long monologue where the reader or viewer gets lost.

In Conclusion

Since most opening books violate these golden rules to varying degrees, there’s little choice but to follow the advice I recently received from Boris Gelfand in an online training:

“Replay a large number of games from a particular opening and create your own overview of strategic ideas and tactical patterns. By replaying many games, you will gain a better understanding of what works and what doesn’t in a given opening.”

Then, create your own variations. This can be done effectively via Chessable, where you can create your own course, or via Lichess (free), where you can compile studies. And once you have a clear direction, the variations from opening books can still be valuable—because then you’ll know better which choices suit you.