Within the realm of literary theory and criticism, we have various perspectives that help bridge the gap between an author’s work and their reader’s interpretation. Most of these famous scholars focus on text under the belief that text alone is the sole proprietor of literature’s linguistic understanding and communication. Yet we, as readers, should not value text over images, considering their importance. Both play a crucial role in generating understanding on a simply direct and cosmically spiritual level.

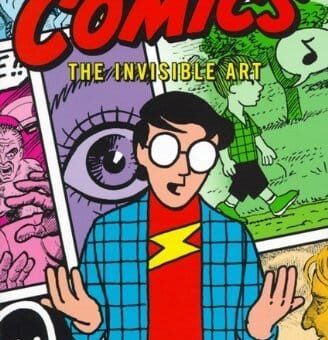

To examine the importance of picture-forward media, we first need to have a precise definition of this art form and the importance of images in conveying understanding to an audience. In the first section of Scott McCloud’s comic, aptly named Understanding Comics, he attempts, with great success, to develop a concise definition for comics, graphic novels, and manga. He describes these art mediums as “juxtaposed pictorial images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer”1.

Today, we use written and spoken language as our communication modality, or in other words, a preferred method of communication. Historically, written communication started as pictorial images, not a language system. These images were used to represent a specific idea or object. What fascinates me is that some of the earliest forms of written communication are crafted through artistic interpretations of time using the white or blank space between images to represent said time. If that is the case, then early images and modern-day language were and still are used to communicate messages similarly. So why is one art form valued over the other when understanding can be obtained through their unification?

As children, we are taught using a variety of methods. One such method is using visuals, like pictures, graphs, and diagrams, to generate an understanding of complex topics. Images can awaken the reader by appealing to different senses. When textbooks combine prose and images together, more positive feedback is generated in a younger audience. This marriage of different art forms “unites the sense – and in doing so, unites the different art forms which appealed to those different senses,” as best stated by McCloud in Understanding Comics. McCloud calls this idea “synaesthetics” and through an understanding of this concept along with an understanding of expressionism, he begs to question the validity of critics’ clear separation of text and images:

“If pictures can, through their rendering; represent invisible concerns such as emotions and the other senses – then the distinction between pictures and other types of icons like Language which specialize in the invisible may seem a bit blurry. In fact, what we’re seeing in the living lives of these pictures is the primordial stuff form which a formalized language can evolve!” 2

McCloud goes on to say that in graphic novels and the like, artists and writers create artwork distorted by expressionism and synaesthetics to produce literary mediums that “foster greater participation by the reader and a sense of involvement” and that “clarify what is being shown… either through the content of surrounding scenes or, of course, through words.” The marriage of these different art forms creates a story palatable to various audiences by giving the reader unique experiences. Readers can obtain this experience by utilizing a medium’s white space to invoke a sense of time and whether that time flows or is at a standstill.

Graphic novels immerse the reader through unconventional techniques that are not explored in mediums that do not have multimodality. Multimodality is any medium that utilizes more than one mode to communicate a story. For example, your favorite subbed anime is multimodal because it incorporates background audio, text translating character lines, and images to convey meaning. Because of the marriage of text and images, graphic novels have multimodality and can convey various messages. Art is inherently subjective, meaning any individual can find something they relate to or understand.

Still, literary scholars have made strides in creating a road map for how words are created and how words come into their significance. Sadly, the same cannot be said about art. Admittedly, art’s subjectivity helps bring into question the viewer’s humanity and experience, which creates a unique, individualistic meaning and experience in each person. Modern-day comics and graphic novels often utilize the union of text and images to create a unique storytelling experience that effectively marries the objective nature of prose with the subjectivity of art. With construction made from concrete words and ever-shifting pictorial images, comics propose a new examination of the communicative and storytelling prowess images add to a literary medium.

When reading a comic, the most interesting concept that differs from the sequential order of images that make up, say, a television program, is the fact that we are the ones who decide when to move on to the next image, panel, or page. The viewer is at the mercy of a schedule regarding television programs. The images are preset to move at specific intervals. Once an image is shown to the audience, we cannot see it again unless we isolate it or rewatch it in its set time. Within graphic novels, images are organized spatially, meaning that the time it takes to process and understand any image is negated unless the artist directly adds temporal aspects to their story. In this aspect, the viewer’s only restriction when reading a graphic novel is the content and form the artist utilizes to convey his unique message: basically, it’s experienced based and differs per reader.

For example, McCloud mentions in Making Comics that the frequent artist’s use of wordless and textualized panels creates aspect-to-aspect panel transitions. Madeleine Rosca utilizes this technique in her original English-language manga Hollow Fields to require more in-depth participation from the reader. An aspect-to-aspect panel transition creates a scene void of time yet can convey immersive details that allow readers to understand the setting. On the first page of the series, the reader is presented with a wordless panel that takes up the entire page. The reader sees a raging storm, a ship at the dock, and many unidentifiable people and buildings. On the next page, the reader is given an aspect-to-aspect panel transition for the first-panel transition of the entire work. While the first page was a wordless panel that set up the environmental setting, the second page’s first panel is an image of the town’s welcome sign that reads “Welcome to Nullsville.” The only aspect shared between the two panels is rain. Keeping a particular aspect intact through multiple panels calls for the reader’s participation by asking them to “assemble scenes from fragmentary visual information.”3

Without text guiding the readers, they can only make an educated guess as to what the novel’s first page indicates or expresses. Even though the first page’s wordless panel showed the reader an environment, it gave no clues as to what the image was trying to convey. The second panel was a town welcome sign, but how are the two panels connected? By the rain shared between the panel transition. With these panel decisions, Rosca encourages her readers to use the rain as fragmentary visual information that connects two seemingly unrelated images.

On the other hand, Alan Moore utilizes the text and images of his comic, Watchmen, to add content and form that emphasizes the reader’s ability to control the time they take to view the next panel or textbox. Throughout Moore’s graphic narrative, we have scene-to-scene panel transitions that, as McCloud states, “transport us across significant distances of time and space.”4 We, as readers, can imagine the movement and action in graphic novels because of the added subjective motion and because of how the graphic narrative uses the white space between each panel as an invisible force. The invisible force ushers the reader into a new “single moment in time,” in which the reader must imagine the action taking place at that very moment5. This space between the panels allows the reader’s mind to “fill in the intervening moments, creating the illusion of time and motion,”6

Chapter four of Watchmen provides excellent examples of this type of panel transition. This chapter, titled “Watchmaker,” focuses mainly on Dr. Manhattan and his origin story. The first two pages of panels are set in the story’s present of “October 1985”, but on page one-hundred and thirteen, a panel jumps to “August 7th, 1945”, an entire 40 years in the past.7 Each time a scene-to-scene panel transitions, time travels. The only way the reader fully understands this time divergence is through the text, which provides pivotal details about the temporal setting of each scene.

Additionally, the text in Watchmen also gives the reader essential clues to understand the reasoning behind being constantly teleported. The text allows the reader to play “detective” and reason how each time transition impacts and improves the story’s sense of plot advancement.8 The abyssal white space separating each panel transforms into invisible lines that connect each panel to create sequential meaning. This allows the reader to gain a precise understanding of the story. In other words, the text in this chapter gives the reader a sense of control.

Honestly, Watchmen can seem confusing and convoluted without the text guiding the reader and helping them traverse the plot. Without the text, the reader could end up with more questions than answers, making any story unappealing. Scenes are given to the reader in frozen and isolated moments, but when these moments are given to the reader using effective flow and panel transitions, the blank spaces between each panel beckon the reader to connect each frozen moment through their imagined motion. The added text in each panel clarifies these moments frozen in time, which helps guide the reader through the content. Without the text, the reader can easily get lost while they traverse each panel’s artwork. Thus, Watchmen’s text is a crucial device to map out and advance through the plot, especially when the panel transitions are scene-to-scene, utilizing spatially and temporally juxtaposed panels to convey a message.

So, when the inevitable scholar knocks on your door, claiming graphic novels, manga, and comics lack sufficient literary meaning because of such and such reasoning, you can readily defend the medium. We can disavow the naysayers by using Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and Making Comics as academic mediums to help us break down manga as works full of literary merit. When we search for literary understanding in manga, we are, in turn, isolating the components that create graphic narratives, text, and images. As we isolate these components, we start to see how they have a communal relationship and how text and images work together to create an art form that delivers a unique message. Apart from how the marriage of text and images creates understanding, the text itself can extend direct, objective, and concise meaning, unlike how images have an inherently subjective meaning. The text also helps pace the advancement of the plot by helping the reader navigate its complex plot and panel transitions.

Also, remember that text allows the reader to connect panels with the invisible wires running through the medium’s white space. The white space is included in manga, graphic novels, and comics for a “single purpose” that amplifies “the sense of reader participation in the manga, a feeling of part of the story, rather than simply observing the story from afar.”9 White space establishes a clear connection with the reader, encouraging them to immerse themselves fully in the story. Graphic novels do not rely on the imagery of words alone to create reader participation. Rather, these graphic novels utilize their artwork in conjunction with the text to inspire readers to participate and don’t all great literary works inspire their readers?

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, 9

︎

︎ - McCloud, Understanding Comics, 127

︎

︎ - McCloud, Making Comics, 216

︎

︎ - McCloud, Understanding Comics, 71

︎

︎ - McCloud, Understanding Comics, 94

︎

︎ - McCloud, Understanding Comics ,94

︎

︎ - Moore and Gibbons, Watchmen, 111-113

︎

︎ - McCloud, Understanding Comics, 71

︎

︎ - McCloud, Making Comics, 216

︎

︎

Header Image: Hollow Fields, © 2007 Madeleine Rosca

Reading in between the Panels, a Critical Approach to White Space by Mark Sullivan – Mark Sullivan