Advanced AI will transform possibilities, and our future will depend on which become real. Deep uncertainties make an AI arms race risky for all sides, yet AI also creates opportunities for unprecedented security. The key challenge isn’t technical feasibility — advanced AI can do that heavy lifting — but navigating from competition to cooperation against the friction of reality: institutional inertia, expectations rooted in thousands of years of state conflict, and sheer failure to recognize unprecedented options.

The Strategic Dilemma

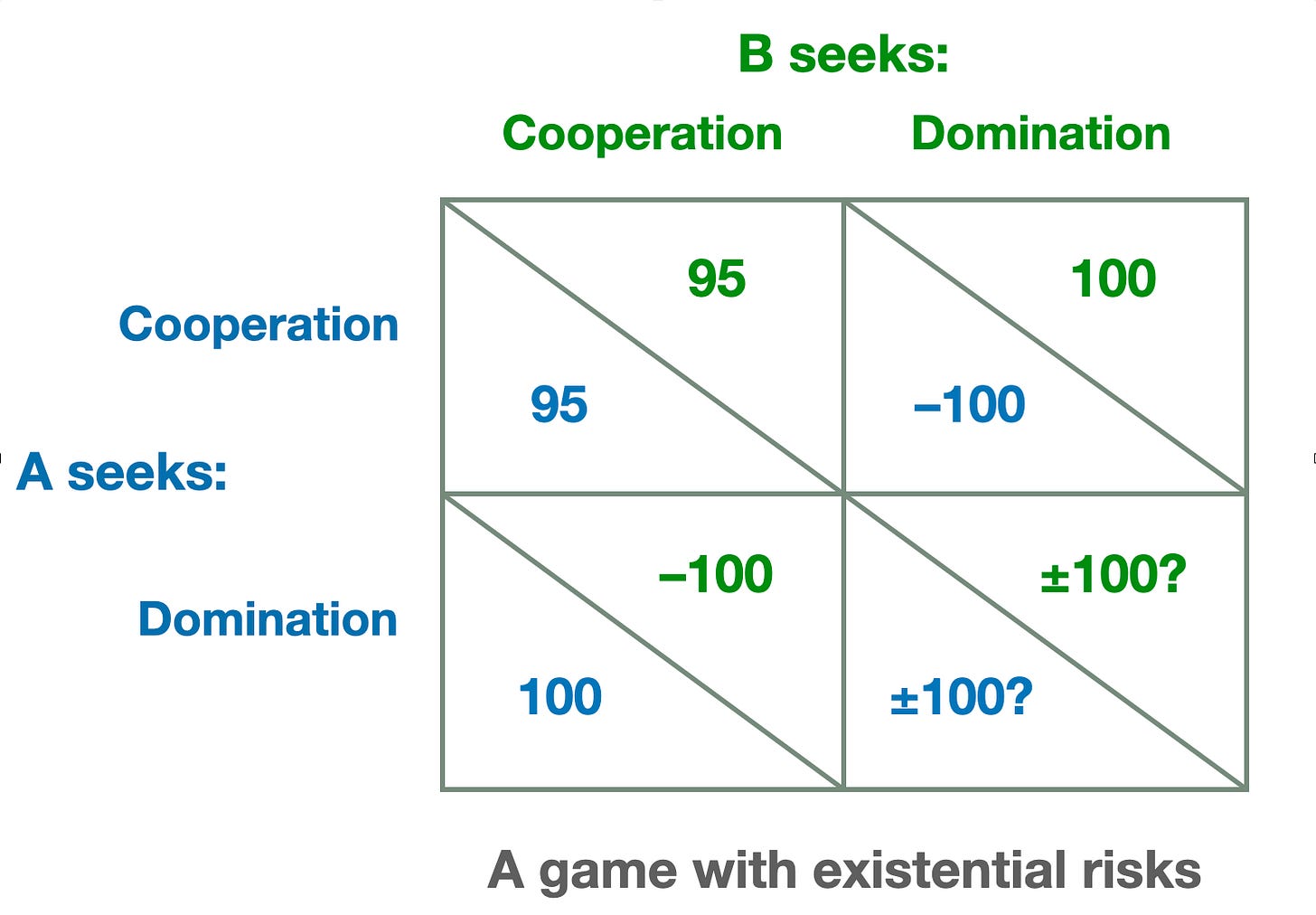

Consider the fundamental strategic choices facing great powers in an AI-enabled world. Each side can pursue either cooperation (seeking defensive stability) or domination (seeking offensive superiority). In a world of profound AI-driven uncertainty strategic calculations cannot be carefully weighed, hence the pursuit of deterrence — peace through strength — in practice becomes indistinguishable from pursuit of offensive superiority. This suggests four possible scenarios, which we can represent as a stylized payoff matrix incorporating uncertainty:

In the upper left, mutual cooperation yields benefits (+95) for both parties (far-from-zero-sum security and material abundance1). In contrast, the off-diagonal scenarios would produce winner-take-all outcomes: a large gain (+100) for a winner and catastrophic losses (-100) for a loser. The lower right quadrant — mutual pursuit of domination — leads to persistent existential uncertainty (±100?) for both.2

Given these payoffs, why don’t states simply choose mutual cooperation? With mutual confidence3 and informed, rational choice, they would.

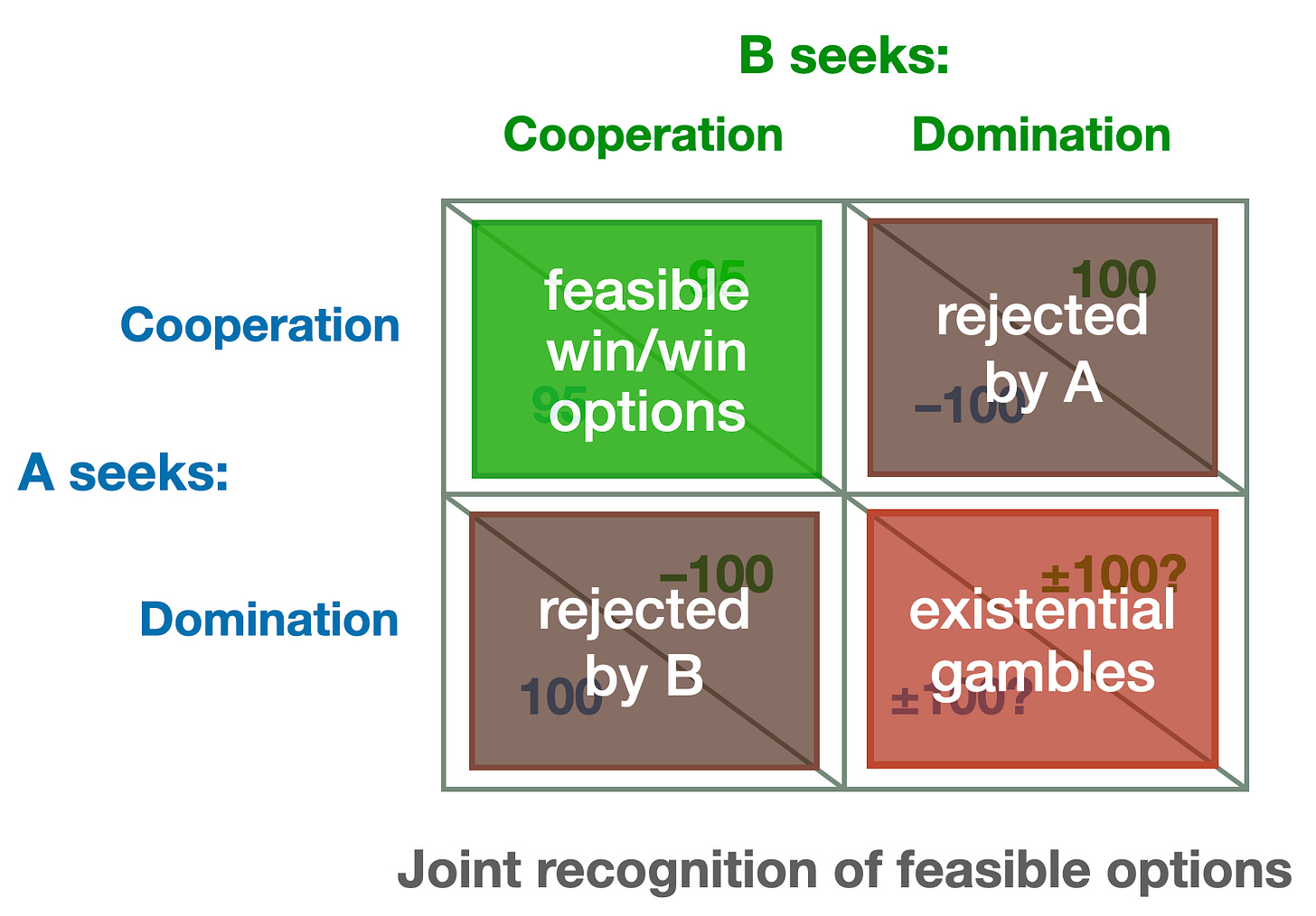

But this analysis assumes that all options are regarded as feasible. In practice, perceptions of what’s possible severely constrain which strategic options are even considered:

The mutual cooperation quadrant is perceived as “not feasible” — the very idea of defensive stability seems implausible on practical, technical grounds. The off-diagonal outcomes are rejected by the disadvantaged party, as no state willingly accepts subordination. This leaves only the lower right quadrant — mutual competition with its deep uncertainties and existential risks — as the only option widely regarded as realistic.

This perception represents a failure of knowledge and imagination, a failure to more deeply consider how advanced AI can be used. A common assumption is that superintelligent-level AI can do almost anything — yet is implicitly assumed to be unable to enable defensive stability. Discussion of this option has been almost invisible.

Recognizing Feasible Win-Win Options

Yet with sufficiently general implementation capacity enabling design and deployment of unprecedented defensive systems, the mutual-cooperation quadrant becomes a feasible target:

Advanced AI transforms defense by enabling massive deployment of precisely constrained weapon systems with verification frameworks aligned with the principles of structured transparency. These technologies can establish robust defensive stability through verifiable capabilities rather than trust, making the upper-left quadrant a feasible end-state for strategic competition. (Robert Jervis’s framework for understanding how states can escape security dilemmas provides a foundation for this analysis.4)

The feasibility of defensive stability creates an objective alignment of interests, yet even if this were recognized, political and institutional barriers would impede its realization.

The Challenge of Transition

How, then, might states steer away from the risky arms-race quadrant to the quadrant of military stability? This transition faces three major obstacles:

-

Knowledge gaps: Potentially asymmetric failure to understand the feasibility of cooperative outcomes.

-

Institutional inertia: Military and political establishments organized around win/lose strategic objectives.

-

Trust deficits: Fears that an adversary will exploit moves toward cooperation to achieve competitive gains.

These obstacles make moves toward cooperation difficult to initiate.

Coercive Cooperation: Pressing for Win-Win Outcomes

This prospect motivates the concept of “coercive cooperation” — the use of pressure to move an adversary toward mutually beneficial outcomes despite knowledge gaps, institutional inertia, or weak foundations for trust.

Unlike typical coercion, which seeks concessions, coercive cooperation aims to establish arrangements that benefit both parties. The coercion is directed not toward zero-sum gains, but toward realizing positive-sum potential.

For example, if Party A recognizes the feasibility of mutual defensive stability while Party B remains committed to offensive dominance, Party A might use multiple pressures to push Party B toward the safer, cooperative outcome that objectively serves Party B’s interests. These pressures will emerge largely from dynamics already in play:

-

The persistent existential uncertainties of an unconstrained arms race5

-

The intensifying risks from accelerating development cycles

-

The application of traditional forms of diplomatic leverage

The crucial distinction is that Party A is pressuring Party B to overcome internal obstacles (knowledge, friction) to self-interested action. What is more, Party A can safely assume that these pressures will align with the preferences of some analysts and decision makers within Party B’s institutions. The value of avoiding a polarizing, visibly confrontational stance should be obvious.6

Seek Credibility From Facts

The prospective credibility of coercive cooperation rests on its alignment with legible objective realities:

-

Technical feasibility: The viability of defensive systems and verification frameworks becomes a concrete basis for discussions, aided by open-source analysis of superhuman depth and rigor.7

-

Strategic feasibility: Building on feasible technological options, open-source strategic analysis provides deep, comprehensive, and persuasive assessments of a range of strategic options for achieving security.

-

Mutual benefits: The coercer’s proposed strategic framework manifestly reduces risks for both parties, lending credibility to the coercer’s intentions.

-

Inevitable consequences: AI-driven strategic uncertainty ensures that continued win/lose competition risks national destruction as a natural consequence of the situation — not as a “punishment”.

The latter point deserves closer attention. In The Strategy of Conflict, Thomas Schelling distinguishes two kinds of coercive pressure: “warnings” and “threats.” A threat is Party A’s promise to impose punishment on Party B if demands aren’t met — a costly commitment that may or may not be credible. A warning, by contrast, communicates what Party A will do contingent on Party B’s actions, not because of a prior commitment, but because of the logic of the unfolding situation. In the context of a risky arms race, a coercer might forgo threats in favor of warnings of inevitable risks of national destruction, an approach that may be both more credible and less provocative.8

A further consideration comes into play: If Party B rejects mutual security despite understanding its feasibility, this stance signals potential hostile intent. Party A’s intensified military preparations would then represent a natural response, not a punitive measure.

Of course, the available tools of statecraft will include a full range of threats, despite their potentially toxic side-effects.

From Existential Gambles to Mutual Security

Realistic pathways from existential gambles to mutual security must be incremental, even if AI mechanisms may radically accelerate the increments. Advanced AI can provide both analytical tools to design these pathways and implementation capacity to deploy the necessary systems.

This transition differs fundamentally from traditional arms limitation agreements that seek to “stop the arms race”. Instead, it redirects competitive development toward defensive systems and verification technologies, building directly on AI capabilities, institutional expertise, and industrial capacity developed during arms competition. Defense contractors, intelligence agencies, and military research establishments would find expanded roles in designing, producing, and deploying advanced defensive systems at potentially unprecedented scale. Extensive technological continuity from offensive to defensive applications means that competitive investments become foundations for defensive security rather than stranded assets.

In a transition to defensive security, AI can help:

-

Design robust verification frameworks that provide confidence while protecting legitimate secrets9

-

Analyze complex scenarios to identify both risks and win-win opportunities that human analysis might miss

-

Model transition pathways that can provide smoothly risk-reducing off-ramps from the midst of an accelerating AI arms race10

The result of a successful transition could be a world where great powers maintain autonomy and security while avoiding profound and incalculable risks. The prospect is a world where defense dominates offense, mutual verification replaces mutual suspicion, and material abundance overwhelms zero-sum competition.

AI capabilities will radically expand humanity’s implementation capacity, creating options that call for new strategic thinking. Our greatest challenge today is to align what is perceived with what is possible: We must understand our options to rethink our goals.

Prospects for radical material abundance are founded on considerations discussed in “The Platform: General Implementation Capacity”; the feasibility of defensive security (see “AI-Driven Strategic Transformation: Preparing to Pivot”) rests on the same foundation; the smallness of material gains (in the payoff matrix, 100 vs. 95) reflects further considerations discussed in “Paretotopian Goal Alignment”. This small difference, premised on material welfare, may undervalue the joys of crushing an adversary, reclaiming sacred national soil, etc.

Fortunately, all parties can enjoy the pleasure of thwarting their adversary’s assumed plans for world domination while fulfilling their own well-advertised vision for global prosperity and peace.

A situation analyzed in “Don’t Bet the Future on Winning an AI Arms Race”.

Paths to coordinated, defensive security must include confidence-building measures.

Robert Jervis (in “Cooperation under the security dilemma”, 1978) identified how security dilemma intensity varies with two factors: whether offensive and defensive weapons can be distinguished, and whether offense or defense has the advantage. Advanced AI enables what Jervis termed “offense-defense differentiation” at unprecedented scales — verification systems can distinguish defensive from offensive forces, while AI-designed defensive technologies can provide security without threatening others. This shifts the strategic environment from Jervis’s most dangerous category (offense-dominant, indistinguishable weapons) toward his most stable (defense-dominant, distinguishable weapons), moving the challenge from technical feasibility of mutual security to overcoming institutional barriers that prevent states from recognizing these possibilities.

An article in War on the Rocks, “Embrace the Arms Race in Asia”, argues that arms-race dynamics have historically been more benign than commonly assumed, challenging (for example) the conventional wisdom that pre-World War I weapons buildups were a key cause of conflict. However, the conditions that the author identifies as potentially benign — gradual, predictable military competition between rational actors — do not apply to AI development.

Party B should of course be welcome to reciprocate by applying similar pressure to Party A. Indeed, under the pressures of an inherently risky arms race, forces driving coercive cooperation begin to act as soon as either party recognizes and advocates the alternative.

Regarding the fundamental viability of defense dominance in a world of steerable, superintelligent-level AI resources and enormous implementation capacity, concrete, attractive options will be as complex as other real societal-scale sociotechnical systems. The results of any realistic analysis, however, will be consistent with a simple truism:

“Advanced AI resources, properly positioned, can thwart anything.”

For example, even if stopping an engineered pandemic were impossible, advanced AI resources (if properly positioned) could monitor gene synthesis everywhere and intervene to thwart the creation of pandemic organisms.

Considering this level of intervention capability immediately suggests dystopian prospects, but these have many potential sources. Advanced AI will be a necessary component of any realistic solutions to the broader problem of governing transparency and the exercise of power.

This distinction is often illustrated by a pair of scenarios: “If you attack our homeland, we’ll defend ourselves” is a warning requiring no special credibility because the action follows from inherent interests — it isn’t a conditional promise to pay a cost. By contrast, “If you attack our ally, we’ll respond with a nuclear strike” is a threat that creates a deterrence credibility problem: The threatened action may be so risky or costly that its execution becomes implausible.

See “Security without Dystopia: Structured Transparency”. It is important to note that uncertainty is sometimes stabilizing, and that the obverse of structured transparency is tailored opacity.