Late last year, Jazzhole Records, with the support of Studio Monkey Shoulder, released two LPs: Eroya and Asiko Tito. Both records are anthologies of music drawn from diverse African and Afrodiasporic genres, Jazzhole Records’ speciality. The release of both records, particularly Eroya, is timely.

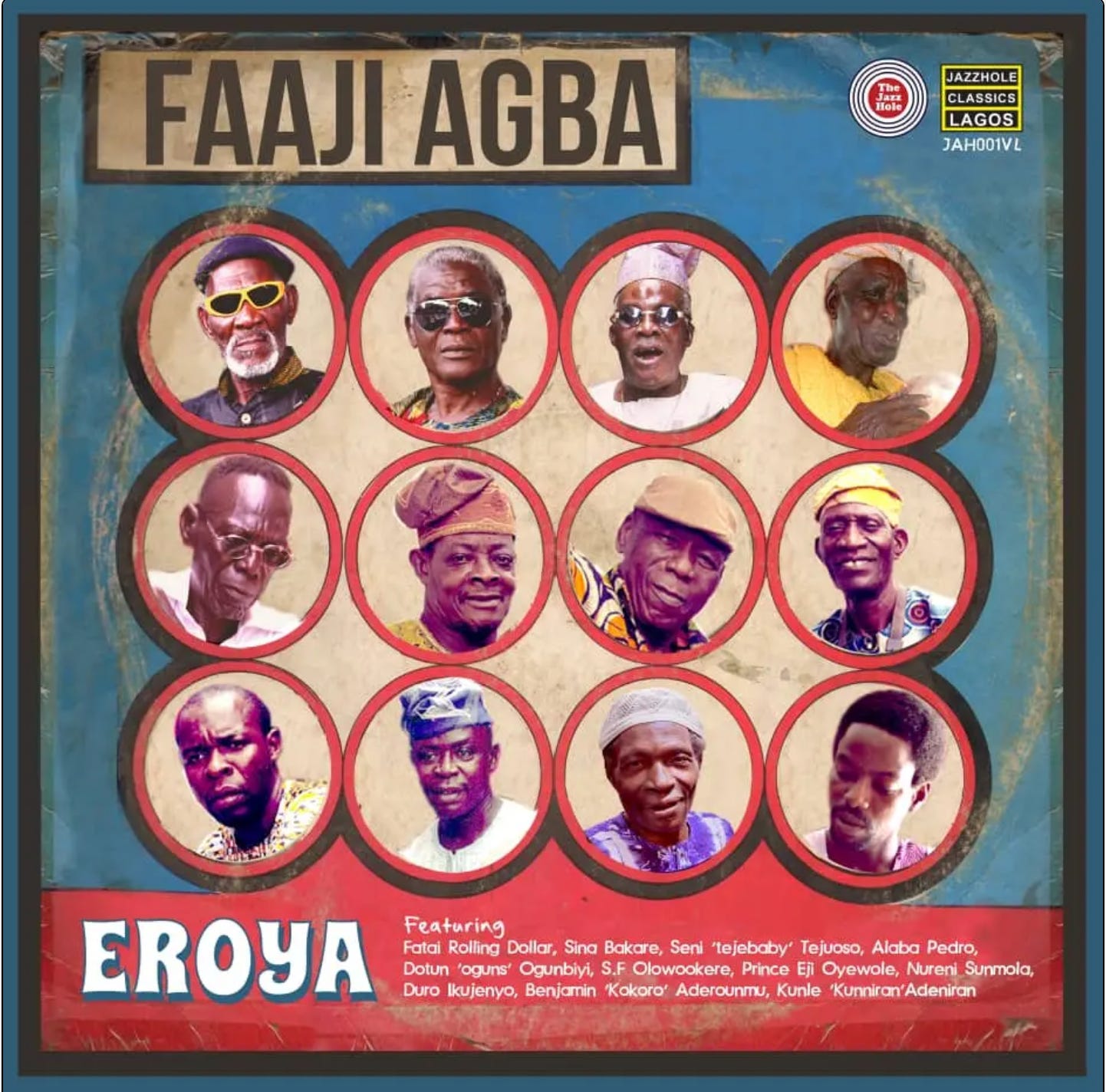

Eroya was released by Faaji Agba, a collective of twelve musicians. Most of these musicians were elderly and have passed on, but this does not diminish the importance of their music. Culture revivalist, archivist and head honcho at Jazzhole Records Kunle Tejuoso should be proud of this 42-minute excursion into Nigeria’s rich musical history through 10 songs.

A word on translation. A Dictionary of the Yoruba Language (University Press PLC, Ibadan 2015) translates ‘Faaji’ to pleasure, leisure, ease, and comfort. Faaji’s etymology is textually similar to the word ‘Fuja’, which the dictionary mentioned above translates as boast or brag. As a Yoruba speaker, I agree that Faaji is pleasurable, leisurely, and comfortable—but it is also much more. It is sanguine. It unifies. It is typically practised when the sun goes down. It requires cold beverages, preferably alcoholic. It involves songs and music. I suspect that the English word ‘revelry’ best captures it. The Dictionary of the Yoruba Language translates revelry to ‘Ariya Alariwo’, noisy mirth. Agba means older adult. Faaji Agba means Older Adult Revelries.

As an avid Yoruba culture and music student, my decade-long preoccupation has been attempting to fold contemporary Nigerian music back into the tradition and legacy of our forefathers. I believe that Afrobeats became a formidable genre when it began to lean more on its African rather than its Afrodiasporic roots. I expect the music to grow if it leans into its rich heritage. This is why Eroya is important.

‘Eroya’, the title track, is Fatai Rolling Dollar’s cover of an earlier version. ‘Eroya’ was originally written by Ambrose Campbell and recorded by the West African Rhythm Brothers, the first Black Band in London. Campbell’s rendition is minimalist, while Dollar’s version is flamboyant with horns, relentless percussion, and the whole shebang. Dollar owns this song, which begins sombre with a mother’s warning and ends with a rallying cry beckoning to an audience. This is not the only Ambrose Campbell song featured on this LP.

Seni Tejuoso’s ‘Africa’ borrows verbatim from the West African Rhythm Brothers’ ‘Ominira’. Instead of eulogising Yoruba statesman Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Tejuoso mumbles some Pan-African Uhuru messaging. Somewhere between Fatai Rolling Dollar’s competent cover and Tejuoso’s mumblings, Eroya calibrates itself as a nostalgic ride to the Golden Age of Nigerian music.

Between the 50s and 60s, appropriate technology, timely politics, and economic prosperity converged in what has been described as the Golden Age of Nigerian music. It was a time of anthemic highlife music when brass bands ruled the nights. Yoruba music that had adopted the palmwine guitar for its rhythmic reinvention, Juju music, placed second. With more than twenty years in evolution and in the hands of a new generation of modern musicians, Juju music would knock out older music genres, Sakara and Apala, out of the pack in the 70s. However, in the 60s, Juju was still finding itself.

Shina Ayinde Bakare delivers the extraordinarily wise tune ‘Inu Mimo’ on Faaji Agba. It is difficult to determine if this song is a cover, but he relies on his father, Ayinde Bakare, ’s earthy approach to Juju music. Ayinde Bakare is one of the Juju musicians who did the foundational work of elevating and modernising the genre. The other three are Ambrose Campbell, IK Dairo, and Tunde Nightingale.

Ambrose ‘Rosi’ Campbell was part of the Jolly Orchestra, an early Juju band popular in the 30s before he migrated to the United Kingdom, where he released several records that were later covered by Sunny Ade and Ebenezer Obey early in their careers. If Faaji Agba consciously skips IK Dairo’s influence, Tunde Nightingale’s achievement on the guitar is inescapable.

SF Olowokeere’s masterstroke of Owambe music immortalizes Tunde Nightingale’s guitar work on ‘Oge Gele’. In his lifetime, Olowokeere affirmed that he followed Nightingale’s framework down to the falsetto. ‘Oge Gele’ is about courtship, Yoruba fashion, and love in the way polyrhythmic Yoruba music attends to different themes within one song. Ironically, his biggest hit, ‘Oge Gele’ became popular during the Biafran war. Paradoxically, SF Olowokeere was denied his royalties till death.

While the work of the Modern Juju Quartet (IK Dairo, Tunde Nightingale, Ayinde Bakare, Ambrose Campbell) cleared the path for Juju, the influence of highlife remained. It was much later in the 70s when Juju separated itself significantly from highlife. This is why you would hear Alaba Pedro’s highlife tune, ‘Eka Ete’, and echoes of Tunde Nightingale’s guitar work persist. The misogyny on ‘Eka Ete’ is also noteworthy. Alongside Dotun ‘Oguns’ Ogunbiyi’s ‘Ara Me RiRi’, these songs are unpleasant in their objectification of women. Misogyny may have gone unchallenged in 50s and 60s Nigeria, but not today.

The Ibibio/Efik name Ekaette which means ‘Little Daughter’, was coopted in the song by Alaba Pedro to objectify. In the first verse, she is pregnant. In the second verse, she has contracted Gonorrhoea. Both uncomfortable scenarios are accompanied by jumpy percussive music punctuated with Prince Eji’s fine sax work, bracketed with Owambe-styled talking drums that give the song that lively Yoruba highlife/juju vibe. It belies the commodifying gaze the song highlights. Oguns’ off-key performance is more pointed in its misogyny towards women who exist out of wedlock.

Even though misogyny transmitted across music genres from the 1960s to the lively Afrobeat and Afrofunk of the 1970s, where pianist Duro Ikujenyo and saxophonist Eji Oyewole operated, their songs, ‘Awo Wesu’ and ‘Experience’ make for pleasant listening experiences.

What is striking about Faaji Agba is how much cultural history it turns. More than six decades, and a listener may be mistaken by how vibrant, relevant and fresh this music recorded at least a decade ago sounds. White ethnomusicologists usually do this kind of work with exhaustive field and liner notes. Here, you have an excellently produced anthology, and in lieu of liner notes in text, Faaji Agba, Remi Vaughn’s documentary film, is available for viewing on YouTube.