This article was posted on Brownstoner.com 5/21/25. Some illustrations are different. Please check it out.

The view of Manhattan from Brooklyn Heights has always been impressive, even in the centuries before the Promenade, the skyscrapers, and the densely populated streets of the city. The Lenape people called the bluffs overlooking the East River “Ihpetonga,” the “high sandy bank.” When the Dutch began colonizing New Amsterdam, the highlands that would become residential Brooklyn Heights were not seen as particularly valuable land, but the lowlands were – perfect for commerce and industry and, in the earliest days, even a bit of farming. The first ferries to Manhattan were established as early as 1642, primarily serving farmers taking their goods to the markets across the river.

Highlands are important to defense, so Brooklyn Heights was fortified by the colonists before the American Revolution. But that strategic advantage was lost in 1776, as General Washington and his men fled New York after the disastrous Battle of Brooklyn in Gowanus, one of the earliest battles of the war. The British occupied both Brooklyn and Manhattan for the duration of the war.

Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont arrived in Brooklyn from New Haven, Connecticut in 1801. His family was prominent in his native New England; his grandfather had been one of the founders of Yale University. When he came of age, young Pierrepont went into the family shipping business. He moved to NYC in 1790 and worked as a clerk at the Customs House. Three years later, he partnered in a mercantile partnership called Leffingwell & Pierrepont. Before the age of 30, he made and lost a fortune, as well as one of his ships.

He came to Brooklyn to start over. He purchased the 60-acre Livingston estate in Brooklyn Heights, a prime piece of property that included the Livingston Brewery, which he converted into the Anchor Gin Distillery. He married wealthy Anna Maria Constable of Philadelphia and invested in Robert Fulton’s ferry project, realizing that a rapid commute between Manhattan and Brooklyn would be quite valuable to Brooklyn’s development. Fulton’s ferry was a huge transportation and financial success.

After receiving a large inheritance of upstate New York land from his father-in-law’s estate, he closed the distillery and concentrated on developing his Brooklyn Heights acreage. His dream was an upscale suburban neighborhood, enticing wealthy Manhattan businessmen who could live away from crowded lower Manhattan yet still commute to their businesses and banks quickly thanks to the ferry. One of his ideas was the creation of a promenade along the Heights, where wealthy families could see and be seen as they strolled along taking in the sights. That dream would come into fruition more than 150 years later and, ironically, would contribute to the end of the warehouses that make up the rest of this story.

The Development of the Walled City

The topography of the shoreline along the East River was perfect for the creation of piers and wharves. The harbor and the river are deep and wide enough to accommodate large vessels. As the Manhattan side filled up, Brooklyn offered even more and better opportunities for shipping, as well as manufacturing.

Thanks in great part to the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, by mid-century, the shoreline from Williamsburg to Red Hook was full of ships loading and unloading goods. Shipping became Brooklyn’s largest industry. Merchants, factories, and shippers flourished along the river, producing and shipping everything from sugar to benzine. The merchandise being shipped in and out had to be stored somewhere, hence the need for “stores,” or warehouses.

The Atlantic Dock Company was established by Daniel Richards in 1839. He created an artificial inlet that contained docks and warehouses at the top of Red Hook, near today’s Hamilton Avenue and the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel entrance in Carroll Gardens. His aim was to capture the vessels coming down the Erie Canal. The docks were built beginning in 1841 and the warehouses in 1844. In 1846, Richards built the first steam-powered grain elevator in Brooklyn. As goods came down the Hudson from upstate, Richards captured a great deal of the traffic, making Brooklyn one of the busiest ports in the world.

Just around the bend going towards the Gowanus Creek, the Erie Basin was an artificial breakwater built by William Beard beginning in the 1850s. The Basin was designed to be a much larger protected port for ships and barges traveling down the Hudson from the Erie Canal as well as from around the world. Many of the ships in the harbor were loaded with rocks as ballast until cargo was loaded.

Beard invited them to dump their ballast in his basin, allowing him to build up the land upon which he built his piers and warehouses, creating 135 acres of docking space. The Erie Basin opened for business in 1864 and soon became one of the most important ports for grain, cotton, and other goods. The Basin also housed ship building and repair docks. Today’s Food Warehouse, formerly Fairway, is at the base of the Van Brunt Stores, one of the groups of 19th century Beard warehouses still standing within the Erie Basin.

After the Civil War, Brooklyn’s importance as a shipping port increased even more. The number of individual piers for shipping companies grew and so did the need for larger and taller stores. Around the corner from Brooklyn Heights, in what is now Dumbo, merchant David Dows built his large Tobacco Inspection Warehouse on Water Street in 1868. The building was originally five stories high and designed, as were all the stores all up and down the coast, as long brick buildings with round arched doorways and windows. The openings could be closed with heavy iron shutters, keeping out light, moisture, and unauthorized people.

Inside, the building was divided into large compartments accessible by a series of ramps leading to the upper floors. When the shutters were open, goods could also be raised up to each floor with block and tackle pulley systems. This building was designed to store tobacco from the tobacco regions of Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and further into the Midwest. The cargo was shipped by rail and by boat.

Next door, a Manhattan-based firm called Nesmith & Sons built an even larger group of stores. James Nesmith bought his land in 1856. The stores that were on the site at the time burned down in a spectacular fire, enabling him to start over with much larger, more modern buildings. Beginning with the first four-story buildings in 1869-70, the Empire Stores consisted of seven brick warehouses that took up the entire waterfront between Main and Dock streets. They followed the standard warehouse design of round arched windows and doors with iron shutters in a red brick building.

This huge complex could store all kinds of goods from all over the world. Items included animal hides and wools from Argentina, sugar and molasses from Puerto Rico, rubber from Belize, palm oil from Liberia and Sierra Leone, and American merchandise that was destined for England and Mexico.

In 1885 James Nesmith, who succeeded his father, built an addition on the Dock Street side of the complex, this one five stories tall. The architect, Thomas Stone, designed it to complement its neighbor, using a similar colored brick and the same round arch design. A close comparison shows it not to be an exact copy – the windows in the newer building are slightly smaller and spaced further apart, but both retain that two-foot-thick walled construction designed to preserve the goods inside.

In the Heights proper, the Pierrepont family wasn’t yet done with the Brooklyn Heights bluffs. Hezekiah died in 1838. His second son, Henry Evelyn Pierrepont, became one of Brooklyn’s most important men, involved in multiple projects that helped establish Brooklyn as a major metropolitan city. In 1844, he and partner Jacob Leroy merged the five Brooklyn ferries operating at the time into one company, the Brooklyn Union Ferry Company. They had a virtual monopoly on transportation between Brooklyn and Manhattan until the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883.

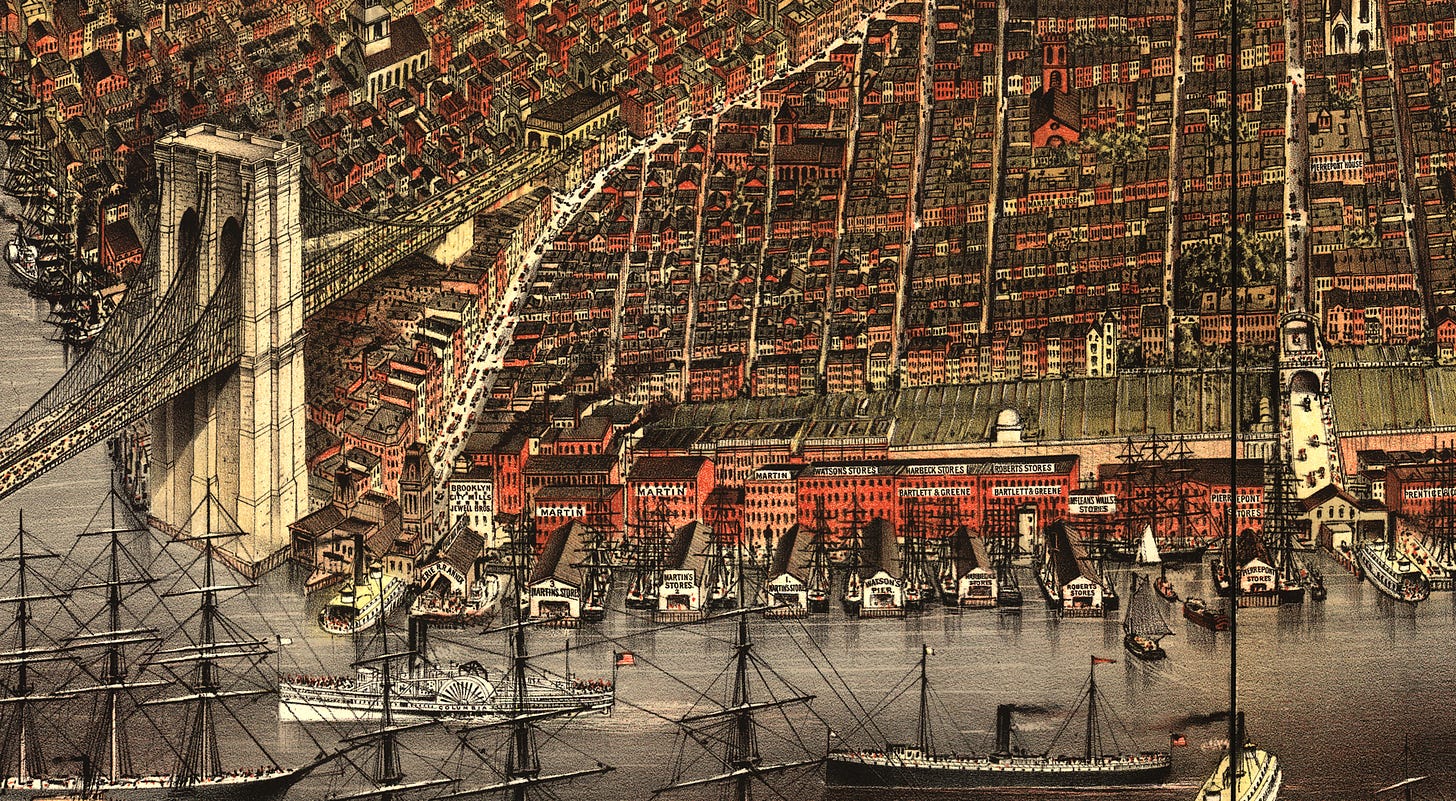

They also established a joint venture called the Pierrepont Stores in 1857. This was a U.S. government bonded warehouse where ships’ freight was unloaded and stored. The merchandise was received and kept there until the government collected the required duties. Pierrepont Stores was a port of entry for a variety of goods but mostly handled sugar and molasses from the Caribbean and the Philippines. They also received shipments of hemp, shellac, hides, spices, and textiles from India and surrounding nations and islands.

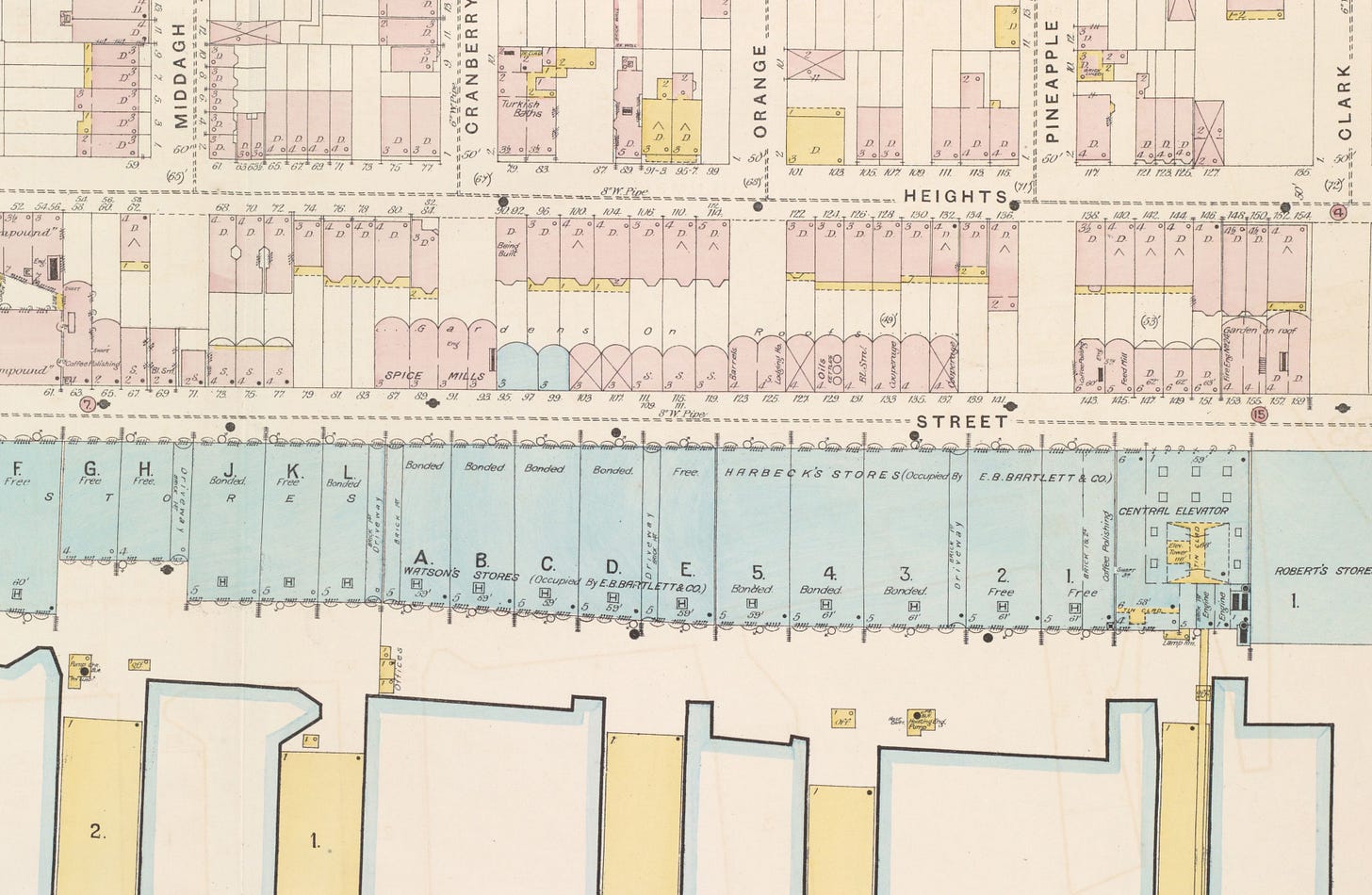

The Perris insurance maps of Brooklyn, published in 1861, show warehouses lining the entire length of the shipping corridor. In Brooklyn Heights, brick warehouses of different sizes belonged to different owners and stretched back towards Furman Street. Furman between Joralemon and Montague streets had rows of wood framed and masonry worker houses, with outhouses lining the back property line, so those warehouses stopped at the property lines. But the larger ones, including those right below Heights mansions such as the Pierrepont mansion, took up the entire block from the shore to Furman.

In those earlier days, only a few piers extended out into the river, and multiple warehouse companies shared them. That would change as time went on. Pierrepont Stores, which had six contiguous warehouses and was a customs port, had its own pier. But by the latter quarter of the 19th century, the number of piers increased, as did the stores.

Most of the new piers had a two-fold storage capacity. The shipping companies built wooden warehouse space on the piers themselves where goods were loaded on or off the ships. Small crafts called “lighters” ferried the cargo to and from the larger ships moored in the harbor. The pier warehouses were temporary storage, where goods were inspected, inventoried, and invoiced. If the merchandise needed longer-term storage, then that’s where the stores came in.

These warehouses were similar in construction to the Empire Stores and the Beard Warehouses. They were three to five stories tall, with windows and doorways only on the back and front. They had either an elevator or a dumbwaiter system in the front, and all had another hatchway in the back. Any light within these block-long buildings was artificial.

Needless to say, fires were a constant worry, with all the combustible materials in the warehouses, so much so that after a few damaging fires, a fire station was built that serviced only the stores.

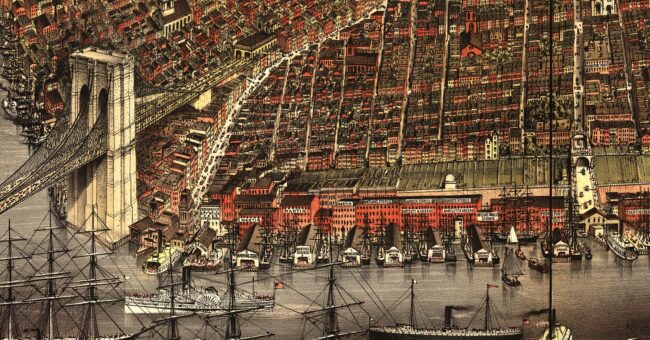

The enormous amount of shipping and storage on the docks resulted in a tremendous wall of connected brick warehouses along Furman Street from the Fulton Ferry to Atlantic Avenue. It was located primarily at the bottom of the bluffs, below the back gardens and greenhouses of the mansions and upscale townhouses of Brooklyn Heights. The stretch of brick inspired “the walled city” as a nickname for Brooklyn, according to the Brooklyn Bridge Park website.

The blocks between Middagh and Clark streets had an extra feature. Beneath the backyards of the houses on Columbia Heights, more three- and four-story storage facilities were carved into the hillside on Furman Street. They weren’t as large as those on the opposite side of the street, but the arched brick chambers extended into the bluffs and became excellent stores for perishables such as plant oils, spices, and coffee. At least one was labeled as a lodging house.

A reporter who toured one of the facilities in 1873 found it to have low ceilings and no light. With the iron shutters and doors, it felt like a prison. It’s hard to imagine anyone sleeping there, especially deep into the bluff with no light, air, plumbing, or second means of egress. But housing laws at the time were lax, especially for housing for the working poor and dockworkers.

High above these caves, the homeowners in their townhouses built gardens on top of the roofs of the caves. The 1887 Sanborn map of the warehouses clearly marks the presence of these storage caves, and the gardens above. In 1946, when construction began on the cantilevered highway under the Heights, construction crews were astonished to find the arched compartments of the stores still intact. All were destroyed to build the highway.

The Fate of the Walled City

In 1888, Hezekiah Pierrepont’s grandsons leased the Pierrepont Stores to the Empire Warehouse Company, the parent organization of Empire Stores. In 1895, the Brooklyn Wharf and Warehouse Company bought up everything along the shoreline from the Empire Stores to the Beard Warehouses. That sale included the Pierrepont Stores, the Atlantic Basin, and all the warehouses below the Heights.

Brooklyn Wharf and Warehouse was a trust run by many of the owners of the various warehouses. Their official documents stated that the company had capital and stock valued at $ 12.5 million, a vast fortune worth billions today. It was thought that if one corporation ran all the shipping piers in that part of Brooklyn, it would be efficient, run like clockwork, and be hugely profitable to those concerned.

They were very wrong. It would be interesting to explore why, but the company went bankrupt only a couple of years after incorporating. The whole operation was sold in foreclosure in 1901. The sale affected 32 piers and their operations and 25 different shipping companies, some small, some — like the Pierrepont, the Empire Stores, Atlantic Dock Co., and the Erie Basin companies — quite large.

The entire operation was purchased by the New York Dock Company for $ 5 million dollars. It was the largest foreclosure sale in the city’s history to that date. In 1911, NYDC sold the Empire Stores to the Arbuckle Coffee Company, which added it to its vast coffee operation. The painted signage for Yuban coffee and the photographs of men unloading raw coffee from across the world became a famous sight.

Other properties adjacent to the Stores were sold to the Jay Street Connecting Railroad, which serviced the many factories now in the Dumbo manufacturing area. The company divided their vast operations into three divisions. The Fulton Terminal included the Heights warehouses, the Atlantic Terminal encompassed the old Atlantic Basin, and the Baltic Terminal comprised the Erie Basin and the Beard Stores.

Now that they were operating in the modern 20th century, they built a railway near Montague Street to move goods. Part of the superstructure for the railroad was a large floating wooden dock supported by pontoons that held four tracks. Mostly the tracks were used to store railroad cars. Railroad cars on these pontoons were pushed across the East River from Manhattan, lifted by a huge (and unsightly) crane, and placed on solid ground where they could be loaded or unloaded and connect to other rail lines.

The Atlantic Dock Company flourished throughout most of the 20th century. The docks along its length became famous and infamous for rowdy sailors and dockworkers, organized crime, big time underworld figures, union activity, and more. The docks inspired the movie On the Waterfront. Its downfall was modern shipping. Container ships are much larger than the steamships of old and need deeper water and more room to dock. New Jersey eagerly made accommodations in Elizabeth and other ports, and most big shipping stopped in Brooklyn in the 1970s.

By the end of the century the Port Authority was in charge of the intact piers, and the unused ones were left to rot. The only piers working were those in the Brooklyn Marine Terminal, which operated until 1983. Today that site is part of Brooklyn Bridge Park, whose creation is a story unto itself.

As for the wall of brick warehouses below Brooklyn Heights? They are all gone, torn down in the late 1940s and early 1950s for the Brooklyn Queens Expressway and its cantilevered three-tiered roadway. There was a harebrained plan by the Port Authority in 1953 to build new storage facilities along the river on Furman Street. They wanted buildings 70 feet tall — 20 feet higher than the Promenade. The Promenade was still new at the time, and already hugely popular. Public opposition was strong, resulting in the city limiting the height of buildings across from the Promenade to 50 feet. In 1974, the city took it one step further, declaring the view from the Promenade protected. No building could be built that would block the view.

Today, sailing ships no longer crowd the river, their masts bristling along the length of the Heights and beyond. The piers and warehouses no longer groan with the weight of goods moving back and forth, and the sounds of dockworkers and equipment no longer rise to meet the gardens of Brooklyn Heights. A beautiful and unique park now runs the length of the shoreline that once was one of the world’s busiest ports, open to everyone. Most people don’t even know that for decades the view of Brooklyn from Lower Manhattan was a wall of warehouses that stretched for over a mile. Brooklyn was the center of the commercial world.