BS”D

Nearly everything your doctor does is based on research published in medical journals – but the journals are revealed by insiders to be completely untrustworthy.

If you’re still clinging to the belief that “science is self-correcting,” or that “peer review ensures quality,” or that “your doctor’s recommendations are grounded in solid science”….

This article will shatter that illusion.

You’re better off flipping a coin than blindly trusting what’s published in medical journals—and frankly, that’s unfair to the coin. The coin isn’t taking bribes from pharmaceutical companies.

Here I’m republishing the majority of two articles by Dr. Wojak, MD. They’re fully documented, and so revealing and critically important to your health decisions that must share the information with you.

First are the stunning quotes, and the details follow. The links to his originals are at the end.

Dr. Wojak:

The Emperor Admits He Has No Clothes

Nearly everything doctors do—what they learn in medical school, what guidelines they follow, what drugs they prescribe, what procedures they perform—is based on research published in medical journals. The entire medical system is downstream from that literature. And doctors don’t verify this research themselves. They simply trust it.

But here you have the editors-in-chief of the world’s most prestigious medical journals unequivocally admitting that the journals are corrupt and the research cannot be trusted.

This is a compilation of damning admissions from some of the most authoritative figures in medical science—top editors of the world’s most influential medical journals: The Lancet, The New England Journal of Medicine, The BMJ, JAMA, and more.

Their statements expose a system corrupted by profit, conflicts of interest, and institutional decay—confirming what the data already shows: modern medicine is deeply compromised, most of the published research is junk, and your doctor cannot be trusted to know the difference.

In other words, the most authoritative figures in medical science admit that the medical system is a sham.

The Admissions

First up is Marcia Angell, former editor-in-chief of The New England Journal of Medicine, where she was an editor from 1979 through 2000. She’s also a physician and currently a Senior Lecturer in Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Next is Richard Horton, a physician who has been the editor-in-chief of The Lancet since 1995. He is also an honorary professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University College London, and the University of Oslo.

Arnold Relman was the longtime editor-in-chief of The New England Journal of Medicine. He was also a physician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He served as editor of NEJM from 1977 to 1991 and was the only person to have been president of the American Federation for Clinical Research, the American Society for Clinical Investigation, and the Association of American Physicians.

Drummond Rennie is a physician who has served as deputy editor of The Journal of the American Medical Association since 1986. He was previously deputy editor of The New England Journal of Medicine and is currently an adjunct professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Richard Smith is a physician who served as editor-in-chief the British Medical Journal and chief executive of the BMJ Group from 1991 to 2004. He is currently director of the UnitedHealth Chronic Disease Initiative at Emory University and chair of the Cochrane Library Oversight Committee. He is also an honorary professor at Imperial College London and the University of Warwick, and a founding Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences.

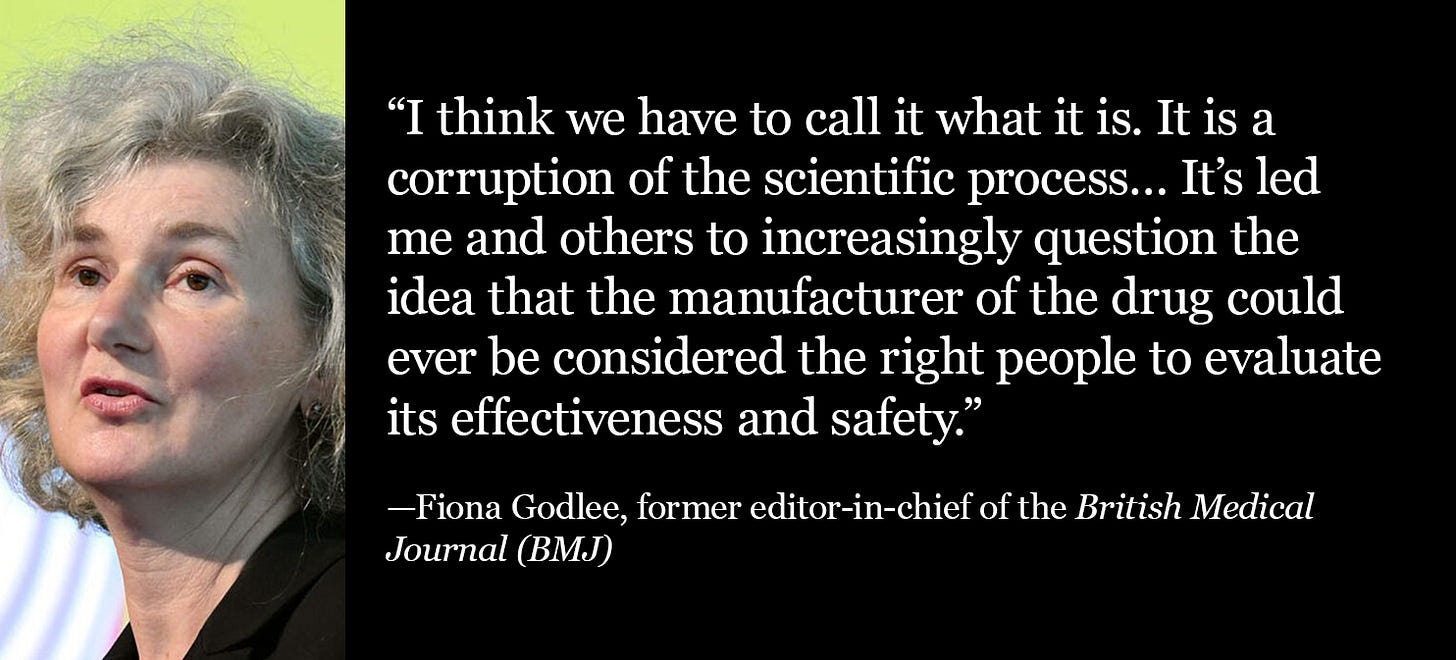

Fiona Godlee is a physician and former editor-in-chief of the British Medical Journal, where she served from 2005 to 2021. She is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and holds honorary positions at the Netherlands School for Primary Care Research and the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Public Health.

Doug Altman was a professor at the University of Oxford and founding director of the Centre for Statistics in Medicine. He was a leading expert in medical research methodology and statistical analysis. Altman also served as chief statistical advisor to the British Medical Journal and was editor-in-chief of the journal Trials. He was a Fellow of both the Academy of Medical Sciences and the Royal Statistical Society.

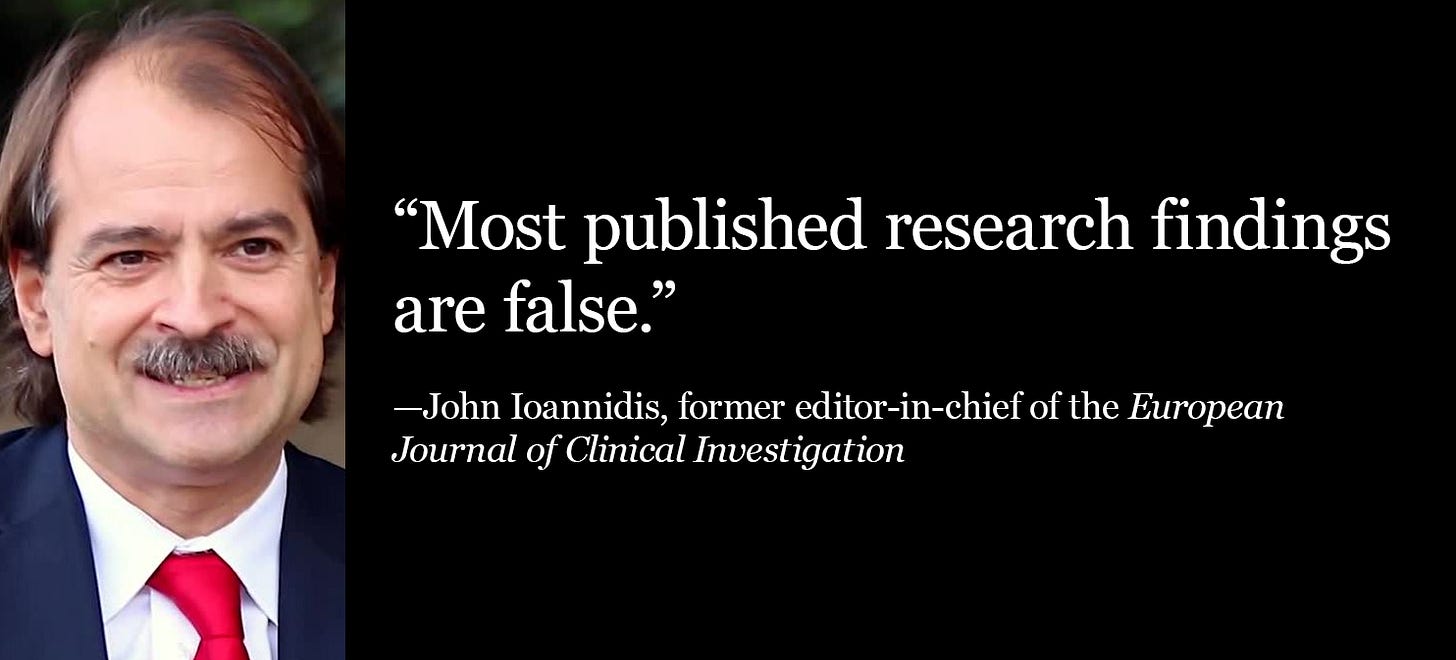

John Ioannidis is a physician and professor at Stanford University with appointments in Medicine, Epidemiology, and Statistics. Formerly chairman of the Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology at the University of Ioannina School of Medicine, he is a leading expert on research reliability and transparency. One of the most cited researchers in the world, he holds an h-index of 239 (Google Scholar, 2023). Ioannidis has served on the editorial boards of over twenty journals, including JAMA, The Lancet, and JNCI, and was editor-in-chief of the European Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Peter Gøtzsche is a physician, co-founder of the Cochrane Collaboration, and former head of the Nordic Cochrane Centre, which he led from 1993 to 2018.

These insiders had little to gain and much to lose by making these admissions. It’s easy to defend a system that handsomely rewards you—much harder to publicly denounce the very machine you’ve spent your career supporting.

For those who want to know in more detail how so much of modern medicine is built on fraud and unreproducible junk, here is most of Dr. Wojak’s full breakdown article:

Most of the Published Research Is Junk

If research can’t be reproduced, it isn’t science—it’s storytelling. Most of academia suffers from a reproducibility crisis (where follow-up studies fail to confirm the original results), but in medicine, fake science doesn’t just mislead—it kills.

Millions of studies flood the literature each year—including over 10,000 retractions in 2023 alone. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Most bad research isn’t retracted. It just lingers—polluting the knowledge base and misinforming generations of doctors, policymakers, and patients.

The Replication Crisis

Just how bad is the replication crisis?

-

Ioannidis (2005) examined 45 blockbuster clinical studies—the kind published in elite journals and cited over a thousand times. Only 20 (44%) were later replicated; the rest were either contradicted, overstated, or never tested again—meaning doctors routinely base treatments on dubious, unverified research.

-

Prinz et al. (2011) evaluated 67 preclinical drug studies. Only 14 (21%) were reproducible. These are the very studies used to greenlight billion-dollar drug trials.

-

Begley and Ellis (2012) tried to replicate 53cancer studies. They succeeded with just 6 of them. That’s 11%.

-

Boekel et al. (2015) assessed 17 neuroimaging studies. Only 1 replicated. That’s 6%.

The problem isn’t limited to obscure journals. This is the mainstream medical literature—the very foundation of so-called “evidence-based medicine.” And most of it is irreproducible or unverified.

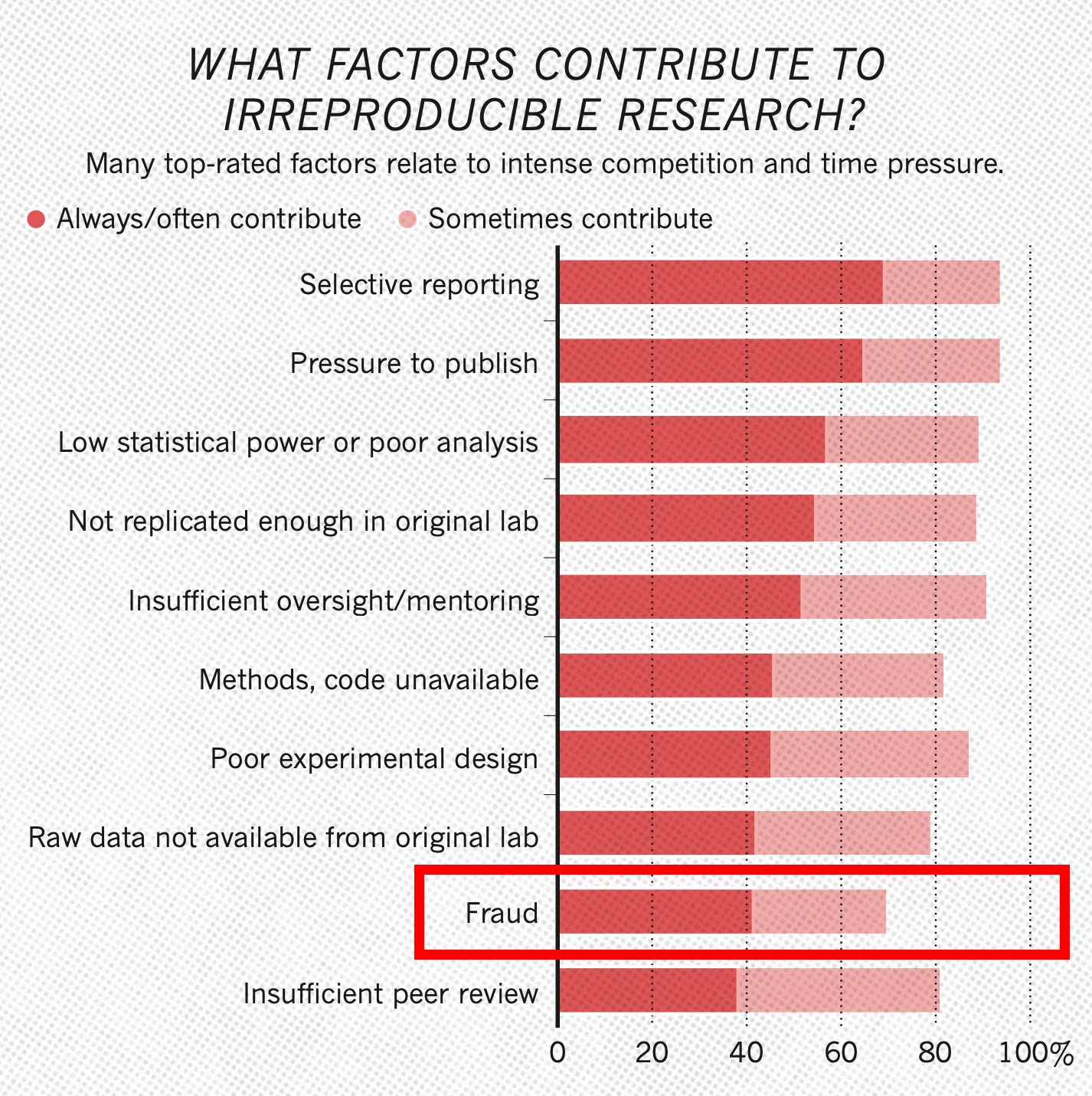

The reproducibility crisis is so severe that 90% of researchers acknowledge it—and the rest are either lying or deeply delusional.

Conflicts of Interest at Every Level

Medical Journals

The revenue of medical journals depends heavily pharmaceutical companies, mainly through advertising and reprint purchases—arrangements that resemble bribes more than legitimate business transactions.

In typical advertising, the goal is to inform potential customers about a product. But in medical journals, pharmaceutical ads serve as financial incentives designed to influence editorial decisions. Similarly, reprints (purchases of specific articles by drug companies) are essentially bribes that influence which studies get published. Without lucrative reprint orders from pharmaceutical companies, medical journals would struggle to stay afloat.

When drug companies want their studies published, they often offer substantial reprint orders if the paper is accepted. A favorable study in a high-impact journal is much more valuable than an ad—it becomes a tool doctors use to justify pushing drugs on patients. Doctors serve as the primary sales force for the pharmaceutical industry, and the junk published in these journals is their ammunition.

In May 2003, BMJ’s cover depicted doctors as pigs feasting at a banquet, being served by lizard drug reps. This spot-on portrayal struck a nerve, prompting pharmaceutical companies to retaliate by threatening to pull £75,000 in advertising. Similarly, the Annals of Internal Medicine lost an estimated $ 1-1.5 million in ad revenue after publishing a study critical of industry advertisements.

As for reprints, even The Lancet—Europe’s most prestigious medical journal—admitted that 41% of its revenue comes from selling reprints. If The Lancet is willing to admit this, it’s safe to assume that the situation is even worse at top US journals, which refuse to disclose their numbers.

The financial stakes are staggering. A 2005 report revealed that publishing a favorable paper could be worth up to £200 million to a pharmaceutical company, with a share of that money flowing into the pockets of doctors who promote the company’s products.

The corruption spans the entire gamut of medical journals—from the most prestigious to niche specialty publications. Transplantation and Dialysis rejected an editorial critical of a drug after three peer reviews—not due to scientific merit, but because its marketing department overruled the editors. Smaller specialty journals are often even more entangled with pharma, regularly publishing industry-sponsored symposia filled with brand names, and crafted to sell products. In one infamous case, Merck created an entire journal itself, packed with ads and favorable articles, dressed up to look like independent research.

Journal Editors

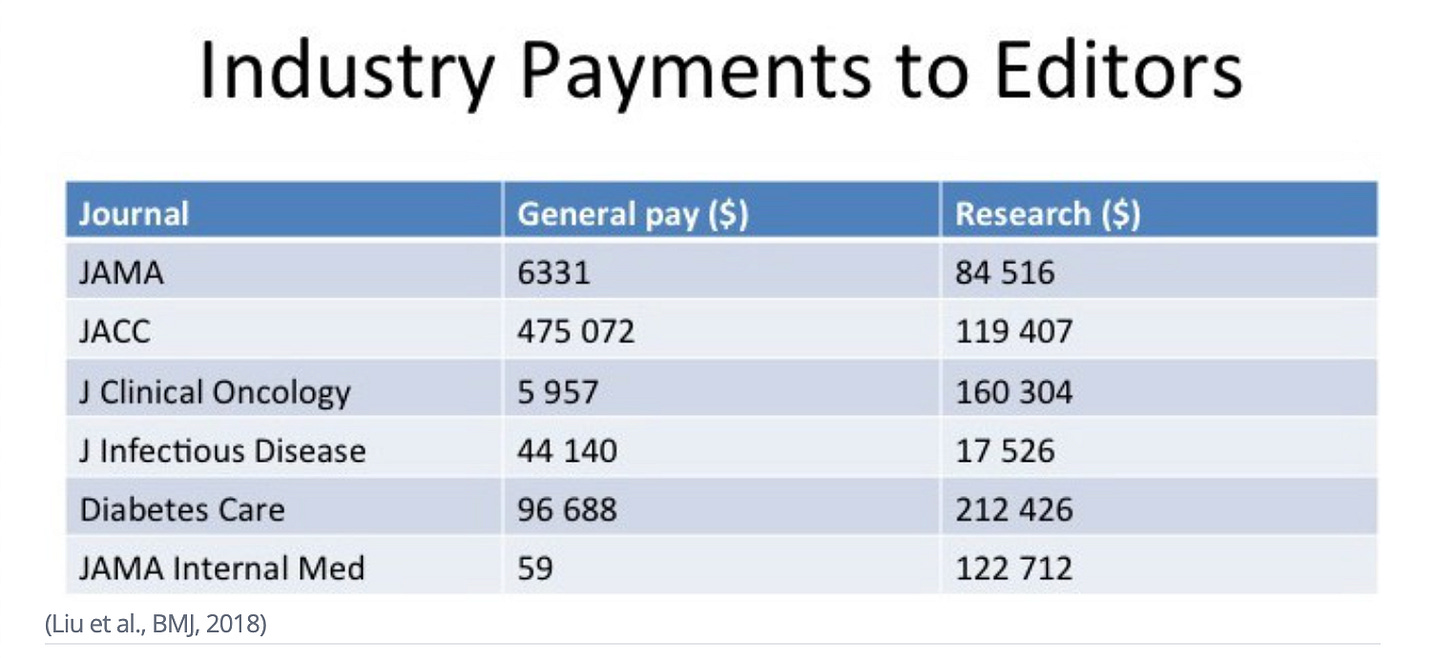

A 2017 study published in the BMJ found that over half (50.6%) of editors at the world’s most influential medical journals were receiving money directly from pharmaceutical and medical device companies—sometimes tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In 2014 alone, the average editor received $ 27,564 in personal payments, plus additional “research” funds—often a loose label for lavish, industry-sponsored perks and travel. At the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 19 editors were paid an average of $ 475,072 each, along with another $ 119,407 in so-called research payments.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials of drugs and other medical treatments are more propaganda than science. Unlike real science, they typically can’t be independently replicated, debated, or scrutinized—because companies control the data and bury anything that doesn’t serve their interests.

The situation is worse than most realize. A review of trial protocols found that in half of the cases, sponsors (i.e. pharmaceutical companies) had the power to block publication. In most others, they could erect legal or logistical barriers. At US medical schools, industry-sponsored research routinely violates editorial norms, including access to raw data and the right to publish findings.

A 2005 survey revealed that 80% of schools would accept contracts giving sponsors data ownership, and 50% would allow sponsors to ghostwrite the study. Even after signing, 82% of institutions encountered conflicts with sponsors. In one case, a company withheld final payment because it didn’t like the study results. Contracts are typically kept secret, making it likely that the true extent of corruption is underestimated. Nonetheless, 69% of administrators admitted that funding pressures often forced them to accept unethical terms. The result is an academic research culture almost wholly corrupted by industry.

Under current rules, sponsors typically own the entire dataset, control who can access it, and allow investigators to view only selected summaries—usually on the company’s premises.

Industry funding now dominates clinical research. In the US, it rose from 32% in 1980 to 62% by 2000. Academic medical centers receive a shrinking portion of these funds—falling from 63% in 1994 to 26% in 2004—with private contract research organizations (CROs) taking over. Many CROs are openly involved in marketing, further blurring the line between research and sales.

To stay competitive, universities court industry dollars, offering access to patients and clinical staff. Doctors are reduced to recruiters, offering up their patients in exchange for perks and publications. In some cases, doctors receive up to $ 42,000 per patient enrolled.

Peer Reviewers

Between 2020–2022, over half of peer reviewers for JAMA, New England Journal of Medicine, BMJ, and The Lancet took money from drug and device companies—$ 1.06 billion total.

-

58.9% received industry payments

-

54% took general payments (like gifts, speaking fees, etc.)

-

31.8% accepted research funding

The median research payment? $ 153,173.

These aren’t fringe journals. These are the so-called gold standard of medical publishing. And the people deciding what gets published are bankrolled by the very industry they’re supposed to keep in check.

Peer reviewers don’t even have to disclose their conflicts—unlike editors and authors. Journals will keep their names and ties hidden from the public.

Biases

Bias Toward Positive Results

One of the most pervasive biases in medical research is the preference for positive findings. Studies that support a treatment or intervention are far more likely to be published, cited, and taken seriously—regardless of their quality.

This bias shows up across the entire research pipeline: from researchers designing studies to journals deciding what gets published. A 2010 study found that papers with positive results were accepted 97.3% of the time, while those with negative findings were accepted only 80% of the time.

The pharmaceutical industry exploits this bias to its full advantage. Drug companies are far more likely to publish studies with favorable outcomes and bury the rest. In one analysis of antidepressant trials submitted to the FDA, 94% of the positive studies were published—but only 8% of the negative ones. If you relied solely on the published literature, it would appear that antidepressants are overwhelmingly effective. In reality, only 51% of all trials showed any benefit at all.

This is the file-drawer problem in action: negative or inconclusive results are quietly shelved, while positive ones flood the journals. It’s not just misleading—it’s deception by omission, and it systematically distorts our entire understanding of medical science.

Publish-or-Perish Culture

Academia rewards volume more than quality. Researchers are pressured to publish constantly or risk losing funding, promotions, or their careers.

Instead of pursuing careful, meaningful research, academics are pushed to crank out papers that are more likely to get published.

The result is a flood of low-quality studies—designed to serve industry interests, pass peer review, and pad résumés. Lots of junk science makes it into journals, as long as it checks the right boxes.

Bias in Study Design

Bias often begins before the research even starts—during the design phase. Researchers craft studies that are more likely to confirm their own hypotheses, introducing confirmation bias from the outset. Even without bad intentions, decisions about what to measure, how to measure it, and how to frame questions can all tilt results in a particular direction. Combined with the pressure to publish and a lack of transparency, these structural biases lay the groundwork for flawed, untrustworthy research.

Fraud and Other Misconduct

Fraud

The problem isn’t just bias or conflicts of interest—it’s widespread, deliberate fraud. The true extent of scientific misconduct is likely much worse than the following numbers suggest, because most researchers are unlikely to admit to fraud—even anonymously.

A survey of 3,247 NIH-funded US scientists found that 33% admitted to questionable research practices in just the past three years, including:

-

16% who altered study design, methodology, or results due to funding pressure

-

15% who dropped inconvenient data points

-

14% who used inappropriate or inadequate research designs

In a broader review of 21 surveys on research misconduct:

-

Up to 5% of scientists admitted to falsifying or fabricating data

-

Up to 33% had personal knowledge of colleagues who falsified data, with up to 72% aware of other questionable practices

-

Up to 34% admitted to other forms of misconduct

Another survey revealed that 81% of biomedical research trainees were willing to omit or fabricate data to secure a grant or publication.

Censorship

Censorship in medical publishing is not just a matter of rejected papers—it often takes the form of targeted suppression, retraction, and professional destruction for those who challenge prevailing industry narratives. Two revealing examples are Dr. Andrew Wakefield and Dr. Paul Thomas, both of whom had peer-reviewed studies retracted and saw their careers subsequently ruined.

In 1998, The Lancet published a paper coauthored by Dr. Andrew Wakefield suggesting a possible link between the MMR vaccine and gastrointestinal issues in autistic children. The study was cautious in its conclusions and openly called for more research, but the reaction was brutal. Under intense institutional pressure, The Lancet retracted the paper, and Wakefield was stripped of his medical license. Whether one agrees with the study’s interpretation or not, the response was not about scientific discourse—it was about enforcing the limits of acceptable inquiry.

A similar fate befell Dr. Paul Thomas, who in 2020 published a peer-reviewed study comparing health outcomes in vaccinated and unvaccinated children in his own practice. The data showed that unvaccinated children experienced fewer chronic conditions. The study was later retracted without serious scientific refutation, and Dr. Thomas had his medical license suspended. The punishment didn’t stem from fraud or methodological flaws—it came from presenting findings that challenged powerful interests.

This kind of censorship isn’t limited to high-profile cases. Entire categories of research that question pharmaceutical products, vaccine policy, or dominant public health narratives are routinely excluded from publication. Journals—deeply entangled with industry funding and reputational concerns—act as ideological gatekeepers. Studies with inconvenient findings are quietly filtered out, while industry-friendly papers are ushered through the process.

Impact Factor

Journal prestige is built on a very manipulable metric—impact factor, which is a measure of how often a journal’s papers are cited. Pharmaceutical companies exploit this metric by orchestrating ghostwritten, secondary publications that cite flawed trial results, boosting both their own marketing and the journal’s prestige.

Take the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), for example. Trials of Pfizer’s voriconazole were published in the NEJM with misleading conclusions, but these flawed studies were cited hundreds of times in other papers, many likely ghostwritten by the company. This citation network artificially inflated the journal’s impact factor, boosting its reputation while spreading corporate propaganda.

By publishing and promoting these biased trials, journals profit from selling reprints, while pharma companies gain more exposure for their products. Impact factor can reflect industry influence more than scientific merit.

What Real Peer Review Looks Like

Real peer review isn’t a behind-the-scenes approval process run by nameless gatekeepers in industry-captured journals.

Real peer review happens out in the open—on platforms like Substack, X, independent blogs, and open-access journals—where anyone can read, critique, and engage with the material directly. No anonymous panels or backroom deals.

More researchers are publishing in open-access and preprint journals, where findings are freely available and subject to public scrutiny. There’s also growing pressure on institutions to publish all results, including negative ones—not just the ones that serve commercial interests.

Unlike the corrupt medical journals propped up by pharmaceutical money, real peer review is decentralized and transparent. It thrives where ideas rise or fall based on merit, not brand-name journals or insider networks.

That’s why the medical establishment fights so hard to control the internet and censor dissent—like we saw during the fake covid pandemic, when too many started thinking for themselves. If free discourse is allowed, their grip on the narrative— propped up by the illusion of journal prestige—starts to slip.

(For Dr. Wojak’s entire (longer) article please see link below.)

Links to Dr. Wojak’s two original amazing articles that all this material was copied from: